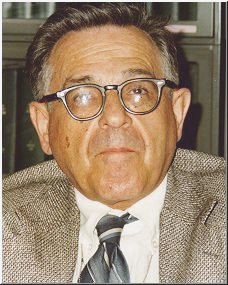

Jacob "Jack" Schmulowitz

Jacob "Jack" Schmulowitz

Jack Schmulowitz began his SSA career in October, 1961 and completed it in September, 1995. During this 34-year span, he remained a researcher and expert on Social Security. He performed hundreds of statistical studies over the years and helped develop many of the standard studies the Agency uses to this day. Jack has been especially influential in the development of the Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin. Jack's encyclopedic knowledge of Social Security has made him a valued expert advisor to several generations of SSA executives.

Jack Schmulowitz in the Historian's Office at SSA Headquarters in Baltimore, 9/13/95

Schmulowitz Oral History

This oral history interview was conducted on September 13, 1995, in the Historian's Office at SSA Headquarters in Baltimore, Maryland. The interviewer was Larry DeWitt, SSA Historian. The tapes of the interview were transcribed by Bob Krebs, Management Analyst in the Historian's Office. (The interviewer's comments and any editorial clarifications appear in italics to distinguish them from Mr. Schmulowitz's comments.) Mr. Schmulowitz edited the raw transcript.

The main focus of this interview is the research program carried out by SSA's Office of Research & Statistics.

Copyright control of the material in this interview is retained by the interviewee and/or the Social Security Administration. It is made available for educational and research purposes only. It can be used and quoted according to the standard "fair use" doctrine. Extensive use or reproduction of this material other than a fair use quotation requires the permission of the interviewee or of the Social Security Administration.

-

Jack can we start at the beginning of your career and tell us about how you came to work for SSA?

Schmulowitz:

-

Well, I was born in December of 1928 so I'll be 67 years old in December of this year. I was born in New York City, in Bronx County, and grew up there and went to public schools there. I then went to what is now the City University of New York . For reasons which I can't understand now, I majored in business administration. I think my father sort of talked me into it, and I graduated with a Bachelor of Business Administration in June of 1950.

I really didn't feel that I wanted to do much in the business world and I didn't know what I wanted to do. I ended up working in a hardware store, starting in September 1950. I took the examination for Public Assistance Case Worker for the New York City Welfare Department, which was then called Social Investigator Grade One. I passed the exam high, but it took a long time to process appointments. I was offered a job and began my career on July 9, 1951 as a Social Investigator Grade One for the New York City Welfare Department.

I'd been sort of neurotic and a little mixed up before, but as soon as I walked in the door of the Welfare Training Institute, which was located in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, I knew this is what I wanted to do. I wanted to work in the social welfare field. I worked in the Welfare Department until 1959. I became a first-line supervisor in 1956. I began feeling that I really had to get a masters degree in social work in order to work in the field in any responsible capacity.

On a tourist visit to Washington I had spoken to someone in HEW (U. S. Department of Health, Education & Welfare), and I got the idea that I really couldn't move there without some graduate study. In 1959 I took an exam that New York state sponsored in which they paid for graduate education, and in return you had to work for them for a year. I took my chances, since two-thirds of the State workers were located in the New York City metropolitan area, that I would be assigned to New York City. I then went to New York School of Social Work, which is the new University School of Social Work. I met excellent faculty members, I learned a great deal and I really enjoyed my time. It was probably one of the most worthwhile experiences I had.

When I got out a year later, --I'd been on an accelerated course, I'd taken some night courses while I was still employed at the New York City Welfare Department,-- I was assigned to Syracuse New York. I hadn't thought this would happen, but statistically things like this happen. I went up to Syracuse, New York and I really didn't make out with the New York State Department of Social Welfare Regional Office. I don't know. I've been tossing it around in my mind for years. Maybe I was a little too brash, and maybe other factors were operating, but I didn't get along. On the other hand, I liked Syracuse and was active in the social workers association chapter and met a number of people at the School of Social Work at Syracuse University.

Kennedy was elected President in November of 1960. I had gone to Syracuse in September 1960 and brought my family four weeks later. My son had been born September 11, 1959, on the day I left the New York City Welfare Department. I remember we saw the inaugural on T.V. in a bar, on a very snowy day in Syracuse. It was a very hopeful time and everyone up at the University said, "move heaven and earth, get yourself down to join the New Frontier." I had two reactions, I wanted to join the New Frontier and I wasn't doing all that well in the State welfare department. I went to New York City in April 1961, and spoke to my faculty advisor at the Columbia School of Social Work, Eveline Burns. Dr. Eveline Burns had been one of the pioneers of Social Security, she had been active in 1935. She wanted me to go on for my doctorate when I finished my master's, and I said I wished to go back to work, I was tired of school. She said okay, I will send a letter to my good friend, the Executive Director of Social Security, Robert M. Ball, which she did.

After awhile I heard from Alvin David, who was head of what is today OLCA (Office of Legislation and Congressional Affairs). At that time they had a research component in Baltimore tied to Alvin David's office, which was called the Division of Program Analysis. There was a research outfit in Washington, the Office of Research and Statistics, which reported directly to the Social Security Commissioner, which Ida Merriam headed. I was invited by Alvin David to apply for a job.

I applied, and they had to submit my application to the Philadelphia Civil Service region to get me a list number as a Social Science Research Analyst. I had let my lease go, because I figured I was going to get out of there. My lease was expiring September 30th, I got a rating in June or July for my first year, which wasn't all that wonderful either, so I knew I really had to go. As luck would have it, the thing was settled and by early August 1961 I had a letter of an offer of employment to go to work in the Disabilities Study Section, Division of Program Analysis.

I accepted it, I remember I had a problem with my vision, I've always had very low vision, probably worse now than it was then. I spoke to the Branch Chief, who was Bill Burke and I told him I had this problem and he had the personnel specialist call me. I think he became head of that group after a while, Al Drummond. Al Drummond said all you have to do is get a doctor's note that your vision's all right to do this kind of sedentary work. I had this problem before going to work for New York City. However, I was in Syracuse and I didn't know any doctor there who I could be sure would say that I could work at the job. I jumped on a plane and flew down to New York and visited the GP (general practitioner) I knew. He didn't answer any of the questions about actual visual acuity but just said I believe the person can do the job. I was called back by Social Security a couple of days later, saying it's perfectly fine, come on down.

I was living in Syracuse, with my wife and our baby who was two years old. I took a bus Friday after work to Baltimore and got in about two in the morning. I asked a policeman where I could stay for the night and he took me over to the Congress Hotel. My wife knew someone's wife who knew someone and I talked to them and I raced around Saturday and Sunday looking for an apartment. I got an apartment around the corner from Sinai Hospital in northwest Baltimore. I came back on the bus that night and got in around seven Monday morning. We packed up and moved out and the next Sunday we drove down. Monday morning I took a bus to work (October 2, 1961).

As soon as I got here I was in the Disabilities Study Section and my supervisor was Phoebe Goff who was the first black in Social Security to get a GS-14 in central office, as far as I know. She was chief of the Disabilities Study Section and I worked with her. Fortunately, she liked me and I met the people in the Disabilities Study Section and they all seemed very friendly. People in that whole group, the Division of Program Analysis, were all very fine people and I knew I was going to make out here. I also figured I already knew more than a number of workers there so things looked very hopeful.

Interviewer:

-

You have spent, essentially, your whole SSA career in research and statistics, is that right?

Schmulowitz:

-

Except for three years. Then I did research in what is today the Office of Retirement and Survivors Insurance.

Interviewer:

-

So your training, masters degree and social work, that was the training you brought to this, or did you have additional training in statistical analysis and so on?

Schmulowitz:

-

No. Regarding my research background, I should have mentioned my contact with Social Security before. I had written my master's dissertation under Eveline Burns, who was an expert on social insurance. I did my masters dissertation on temporary disability insurance, which is the program that's in effect in six States including New York, and New York's program managed by the Worker's Compensation Board. Eveline Burns said send your dissertation to Al Skolnik, who is the in-house expert in Social Security on temporary disability and worker's compensation and let him critique it for you. I mailed it to him and he critiqued it and with some minor corrections said it was fine, at which time Eveline Burns approved it and I received my degree.

I knew I had to live up to my commitment to work for New York State and didn't know that it wasn't going to turn out. But my interest wasn't mainly casework, even though my major was casework. I was already thirty and I was past the age, I thought, where I could begin a casework career at the bottom. And maybe I wasn't all that wonderful as a caseworker because I had been a supervisor for four or five years. I hadn't really dealt with clients since 1956 which was the last time I saw a client in person. I guess I really wanted a research career. I had written on a social insurance topic while most of the students wrote on casework practice topics. I had minored in statistics in college and I took courses in research statistics. I thought I had a reasonable background to be a research analyst.

Interviewer:

-

Your assignment was here at the headquarters in Woodlawn, now was all of ORS, or what was at that time the research organization, here or was part of it in Washington?

Schmulowitz:

-

There were two. The real ORS was in Washington, and Ida Merriam was the director and she reported directly to the Social Security Commissioner. At that time the Social Security Administration was under a thing called BOASI, Bureau of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and within BOASI there was the Division of Program Analysis, which is the present day OLCA plus the research component in Baltimore. I was working for the Disabilities Studies Section, which was like a branch, the Economics Studies Branch, which was like a division under the Division of Program Analysis. That was our research component and the head of it was George Trafton, who was an economist.

There had been a long history of research being carried on in Baltimore, in this Division of Program Analysis. Subsequently, in 1963, the groups were merged and the Office of Research and Statistics took over the Economics Studies Branch, which was the research component in the Division of Program Analysis. The Division of Program Analysis was then renamed the Division of Program Evaluation and Planning (DPEP), which became OPEP (Office) eventually, and Alvin David continued as head of that.

The major thing at that time was the Medicare program. The attempt to put over the Medicare program, which was really begun in 1958 when Wilbur Cohen was on the outside still, I believe he was teaching in Michigan, was Social Security's major interest and Alvin David of course continued with that as his major interest in putting that across in 1965. Ida Merriam, who was also close to Commissioner Ball, was also interested in the Medicare program and a lot of the job done in ORS was sort of in support of the need for health insurance for the aged, which then emerged in 1965 as the three-legged program: hospital insurance; SMI (Supplemental Medical Insurance) Part B; and the Medicaid program. In 1963 we were put under the Office of Research and Statistics.

Interviewer:

-

The impression I've gotten is that at this period in time ORS, the research component of the Agency, was very influential in policy- making in the Agency. And a lot of the analysis that came out of your groups drove policy in the Agency to some degree. Is that a correct impression?

Schmulowitz:

-

I think the research component, not the one I started with but the one in Washington, had a very long and distinguished history. Our first leader, although no one likes to admit it, was Eleanor Dulles, the sister of the famous John Foster Dulles and Allan Dulles. Eleanor Dulles was head of it for a while. Then she was followed by the famous I.S. Falk. Congress I think got mad at him and in the 40s passed a resolution that no part of our appropriation could be used to pay the salary of I.S. Falk. He had to leave and Mrs. Merriam took over.

(Ed. Note: I.S. Falk was forced to resign by the new Secretary of HEW for the Eisenhower Administration. His letter of resignation was dated 12/10/53 and became effective 6/30/54. Walton H. Hamilton and Ewan Clague succeeded Ms. Dulles as Directors for the Bureau of Research and Statistics. Mr. Falk's tenure as Director was from 1940- 1952. He was succeeded by Wilbur Cohn 1953-1956, Ida Merriam became Director in 1957.)

The relationship between Falk and Merriam and people running Social Security, Altmeyer and then Ball, was close and they relied on the work that was done by her group and on her judgement. I think that Ida Merriam and her people provided a great amount of expertise, but also the personal relationship between them and the people who were running the operation began not to exist in the same way after Ball left and after Merriam left. I think part of it was the work we did and the landmark work on poverty and the research with Mollie Orshansky, but a lot of it was the personal relationship between Falk and his management and Arthur Altmeyer and then subsequently Mrs. Merriam and Bob Ball. Some of it was the good work and the leadership certainly was very important, but afterwards it was the other.

Now, with all the things I liked about Social Security, there was a dark side to Social Security in 61 which was very troublesome and that was the race problem. Coming to Social Security from the New York City Welfare Department, which at the time was quite integrated, we had black supervisors and a black commissioner, Social Security really seemed backward coming from the environment I came from in New York City. Whatever it is now, New York City was then the bastion of liberalism and progressive thinking. The lack of black people in leadership positions in Social Security seemed bad and it really was a problem and bothered many of us a good deal.

Bill Burke, who arranged for my hiring, was the deputy in the Economics Studies Branch and he wanted to get the research analysts together every couple of weeks for lunch. The only place we could go was the Marriot Hot Shoppes in Edmonson Village, because the other places were not integrated. We would either have to have lunch in the Executive Dining Room, which we didn't want to use for other reasons--we felt it wasn't egalitarian. We had an executive dining room here, which is now used for hearing and arbitration panels and stuff. We had the choice of going there or the Hot Shoppes. We went to Hot Shoppes every two weeks.

The race problem was serious. I still have a copy of the 1963 edition of the Baltimore Afro-American newspaper talking about the march on Washington on August 15th and on the front page it says "Social Security agrees to study commission." The study commission was under State Senator Mitchell, he must of just been out of Morgan State at twenty-four or twenty-five. He was head of the study group that began Social Security's movement away from its old patterns and into the kind of place it eventually became. Though, I remember it was a long fight and it took the people running Social Security overly long to get on with it. I think they felt they were moving as rapidly as they could in looking for these candidates. There was a dearth of black people to move into professional positions and to leadership positions and it took many years until that kind of talent was developed. Today, half the Deputy Commissioners are black and a large number of Associate Commissioners, but this was a difficult time the early 60s.

As far as I was concerned that was the only thing wrong with Social Security, everything else seemed fine. We were part of the New Frontier and pushing for civil rights here, and the Medicare program. Everything looked very, very hopeful, as it is when you're in such a time.

Interviewer:

-

Let's go back then to that point at the start of your career, you're in the Disabilities Studies Section, it's the early 60s, Medicare is on the horizon, what happened next?

Schmulowitz:

-

Well, as always, I did a little work on Medicare. I worked on disability prevalence and I discovered, which I guess everyone knows about now, that disability prevalence was much higher in Southern states than in the Northern states and rates of disability were very high in the South and lower in the North. That work was my first published research report. Then I spent a lot of time studying the workers compensation offset provision, which wasn't in existence at the time. We had one in the 50s, and I studied the 57, 58 provisions and had my workers compensation report ready for publication, at which time in 65 Congress passed a workers' compensation offset as part of the Medicare legislation.

Medicare passed in 65 and there was a big scurrying around of what to do and everything else and there was a lot of turmoil in Baltimore about the merger. The 63 merger led to most of the Baltimore chiefs being removed, and Mrs. Merriam moved in people she had selected from Washington. For awhile it felt very much like colonial rule, we were here and they were bringing in chiefs from out of this place, and throwing out our chiefs.

I had come in as a GS-11 and received a GS-12 a year or so later. Then I was recruited by BRSI (Bureau of Retirement & Survivors Insurance), which became ORSI (Office of) and today is known as the Office of Program Benefits Policy. I was recruited up because they were working on representative payment. I was to work on and develop a representative payee survey.

I left ORS in 65 and received a GS-13. There were some hard feelings. I think once I agreed to go, ORS wanted to retain me and offered me a GS-13 there. I said, well I gave my word and I'm going.

I went and worked for a special studies group under Charlotte Ellis, which came under Gene Skinner, who was the head of the Rep Payee Branch. I think our overall boss at the time, the head of BRSI, was Neota Larson, who was a social work type and was quite influential in community relations. She was replaced by Jay Roney, after her death. I think Tom Parrot, who was under Dick Branham, was deputy, or had a major position there. It was a very professional group. Some of the nicest people I met and enjoyed working with were up in this representative payee group, when Gene Skinner was the Branch Chief. I became close friends with most of the people in the place. It was a very social group. They went out to lunch every week, and it was a pleasant group.

The rep payee survey never got off the ground much, but Dick Bruhn and I developed the system of representative payee accounting, which has been in effect on and off for years. It's been debated by the Agency, because it's a lot of work and not much pay off. But it does keep an eye on, we felt, the representative payees and keeps some control and some knowledge that the Social Security Administration is trying to monitor what you're doing, and you better do a decent job. We developed an automated system for representative payee accounting and then afterwards developed the on-site review. This was the system for, not having rep payee accounting in the major institutions, but going into the institutions periodically and seeing what they were doing. The review involved talking to the management, talking to a few patients, learning how the books were run, to see that they treated the beneficiaries reasonably well.

The BRSI thing turned out badly in that Mrs. Merriam at the time was pushing to have all research handled by ORS. She managed to get Commissioner Ball to agree to that and there was a directive transferring the representative payee survey to ORS. Here I was in 68 essentially not knowing what I was going to do. The fellow who headed, the beginnings of quality appraisal, which eventually became OPIR (Office of Program and Integrity Reviews), in BRSI, was Milton Freeman. He said if you've got nothing better to do come work for me.

That seemed reasonable, but I did want to get back into research, I didn't want to leave the research area. On the other hand, as people have always said about research types, the ORS types don't burn their bridges behind them, they nuke them. I had sort of nuked my bridges behind me by not staying with ORS when I was offered the same GS-13 that I had accepted in BRSI. I called Mrs. Merriam, I said I'm going to swallow my pride. She did not respond to my calls and finally I phoned some days later and got her in. She said all right since we're doing the payee survey, you can come back.

I came back and by that time the division had been built, the Division of Disability Studies, and Larry Haber was the head of it. I went back very inauspiciously, I don't think they knew I had a desk in an anteroom somewhere. I really had to be rehabilitated or do penance or whatever. I was there doing work in disabilities studies and then, worked a bit on the rep payee survey, but I wasn't going to be given any leadership in it because their claim for getting it was that we didn't know what we were doing to put it together.

Interviewer:

-

Before we go on, you mentioned Ida Merriam several times and she's a major figure in this aspect of the Agency's history. Did you have many dealings with her over your career and were you able to form impressions of her and can you describe her a little bit and how she was to deal with?

Schmulowitz:

-

Yes, later on I did. Ida Merriam was really from the generation of the New Deal type woman, like Frances Perkins. She was a woman in a leadership position. She was highly educated, absolutely brilliant. And knew what it was she wanted Social Security to be like, and what it was she wanted research to be like. In other words she was, for ORS, the same kind of leader that Bob Ball was for Social Security. There was no one like her. When she left and Ball left, the organization wasn't the same anymore. Neither was Social Security the same and certainly ORS wasn't the same, but that's getting me a little ahead of myself.

I'm in ORS in 1968-69 working on a study I developed an information and referral services in district offices, which was fairly well received. Ida Merriam used to call me in Washington when we had these, quote "social-work-type" problems, I think I was the only social worker in ORS at the time, and I did information and referral services and I masterminded a demonstration project in Cincinnati for people visiting shut-ins in the community, which was fun. And then a lucky thing happened. Social Security was trying to move ahead on civil rights issues, and moving rapidly enough for some people and not for others. They decided to form a study group-- Services to the Public study group. They invited ORS to supply a person to go to it. I think Larry Haber asked me if I wanted to go, and partly I think he wanted me not to be around that much, so he invited me to go.

It turned out to be an opportunity. I got myself put in charge of the research sub-group of the study group and the people that were with me on the sub-group were all sort of, active in the civil rights thing and we ran a runaway study group. We weren't supposed to, but I planned with the people with me--I was the only research type and I had the access to the statistics through ORS--a complete study of Social Security's problems with minorities. It was a very ambitious kind of project, which is kind of a rash thing I would never do if I were older. We got this study going that no one knew was going on and I talked to the data people in ORS who secured the data for me. They told the BDP (Bureau of Data Processing) people this was Commissioner Ball's orders.

We had this major study going and we studied hospital utilization under Medicare. I think the key thing was I developed a plan for studying district offices. I took the district offices proportion of blacks and whites in their service areas and compared it to the proportion of employees in the services areas. The answer was Social Security was doing all right in some places, but still doing poorly in others. There were offices with lots of black clients and no black workers, or very few.

In the Services to the Public study group we ended up making our own report on our research. I think the results of the study group were really important to Social Security, though we did get little circulation, a few copies were printed. I have a xerox copy of it, I think I gave away my original copy. We were all very proud of it and Mrs. Merriam was appreciative of this kind of work, even though I guess most of it was done without asking about it. That was one of my high points. A couple of the papers I had written as part of the study group were published. I had written on minority participation in the Social Security program, and it was republished in some other places. The study group I think really made a useful contribution to Social Security and was the first high point in my own career.

Interviewer:

-

It sounds like this may had been the first time we ever undertook a study of this type, is that correct?

Schmulowitz:

-

Probably. It was the first time we undertook it and went completely ad hoc with nobody knowing about it until it was done. It was pretty good and Mrs. Merriam thought it was a real accomplishment to have done it, even though she had her own internal problems. Actually, one of the leaders of the Washington civil rights movement was a worker for ORS who had a certain amount of conflict with the ORS leadership. Julius Hobson, who was an analyst and economist in ORS in Washington, was also the head of CORE (Congress on Racial Equality) in Washington and the major protagonist in Hobson vs. Board of Education. This became the lawsuit that ended the tracking system in Washington, D.C. schools, where they had homogeneous classes for smart kids and not so smart kids and he said that was a cover for racism. So Hobson was a real activist and he fought with Mrs. Merriam a bit, or a lot, and I was close friends with him. However, I was also close friends with his boss Al Skolnik, who had been my dissertation reviewer.

Getting back to the study results, they sort of made me an expert on minority statistics, and on the pragmatic side Mrs. Merriam asked my Division Director, who wasn't really anxious to do it at that point, to post a GS-14 position. So that through Mrs. Merriam, the Division Director did agree that it was reasonable. I did end up being appointed a GS-14 in late 1971.

After the 1968 election Commissioner Ball thought he would be removed, but he was kept. Elliot Richardson was Secretary and I think he liked him. Then in 1972 Mrs. Merriam was sure that Ball wouldn't be retained after the 72 election, he must of told her he wouldn't. She retired in 72 so that Ball could appoint a person she recommended to be the head of the Office of Research and Statistics. That was Jack Carroll. Mrs. Merriam left before the election in 72 and Mr. Ball tendered his resignation the day after Christmas in 72.

(Ed. Note: Bob Ball's letter of resignation to the President was dated 1/3/73, Nixon responded with a letter formally accepting the resignation on 1/5/73.)

However, this is one of the things that's a little hard to figure. Even though Nixon had campaigned a bit on the race issue, talking about the silent majority and things like that, the fact was, he was surrounded in part by an ultra-liberal group. Elliot Richardson was Secretary, Bob Finch was Secretary before Elliot Richardson, and then people from California from the Welfare Department like Tom Joe, who is still at work, were around Finch and Richardson, and they were sort of interested in expanding the programs and were also interested in the civil rights area. The first four years of Nixon were not conservative times and everything at Social Security continued fairly well.

I have to go back a time, I missed my chance for the poverty program. It's one of those things I don't know if I did the right thing. It must of been around 66 or 67, we were invited to a presentation by Sargent Shriver, who was head of the OEO, the Office of Economic Opportunity, which was the vehicle for managing the poverty programs. And we were at HHS, I think, or one of those buildings, hearing Sargent Shriver speak on how the poverty program worked and how it was tied in with the movement and everything else. And I was completely impressed with him and ready to sign on with the OEO. I went back and my wife said, well you know you just got a GS-13 here and they like you and how do you know how long this poverty program will last. If you get tired of it you'll be having to look for a job again or begging people to take you back in Social Security. I ended up not going. I missed my chance to be in the poverty program, which I've always felt badly about because I went through the 60s without being part of the poverty work.

Going into 71 and 72 were periods where Mrs. Merriam was leaving and I finished my work in the study group and was doing some work in the disability area in the Disabilities Studies Division with Larry Haber. My specialty was representative payment, which I continued to work on while I was in ORS.

At that time the SSI program was taking shape. President Nixon had proposed the Family Assistance Program (FAP), which would have been a reform of welfare probably along the lines that President Clinton is talking about now. And I think it would have brought in a much better welfare program and a more uniform program according to national standards. It failed on the basis of if you had too many work incentives then the level of support had to be too high and a lot of people would be getting welfare who didn't seem like they should because they were not making less than people who were not on welfare. On the other hand, if you kept the support standards too low, if you kept it so that only people who worked got any real support, you defeated the program because people would be put on a starvation level. Therefore, the program couldn't get support of conservatives in a liberal form, and couldn't get liberals support in a more conservative form. The FAP program failed.

The only part of the FAP program that was enacted was SSI. SSI, the Supplemental Security Income program, was meant to replace and take over the previous State programs of old age assistance, aid to the disabled and aid to the blind, and provide uniform standards. In effect, it was geared to raise the standards of about sixty percent of the people, those who were in the poorer States, Southern States and Southwestern States. The wealthier States would have to supplement the program. Of course, it got it out of the States' hands, and Congress felt it would end the stigma of getting help through a local welfare office. Instead you would be getting it through a Social Security office which had a better name.

We ended up with a Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program looking like it would come over to Social Security. On the original FAP task force, which then became the SSI task force because there was not going to be the Family Assistance Plan, there was a very brilliant fellow Jim Callison, who was slated to be the research director for the SSI program. He came off the FAP task force and went to work for Mrs. Merriam as a Division Director. The newly formed SSI program, passed in November of 72 with a kick-off date of January 74, and in the interim we were to get ready for it.

He asked me to come over and organize the program statistics for SSI, at which point, this was early 73, I went from the Division of Disability Studies to the Division of SSI Studies and became the Branch Chief of what was called the Analysis Branch. On opening day we had our first statistics out in January of 74. We did a series of articles on the statistical program. That began my association with SSI statistics and then we did a study of conversion experience to the SSI program. We began publishing county data, monthly and quarterly data and demographic data.

Going into the formative stages of the SSI division I was in with, up to that time the strongest group I had worked with, and still the strongest group afterwards. I was the Branch Chief in charge of program statistics. Jim Callison was just a super leader. We had Tom Tissue, a Branch Chief who did a survey on the low income and disabled and how they were before we took over, when they were on the State programs, and how it was afterwards. We had Don Rigby, who handled State administered supplementary statistics. Buzz Goldstein handled the computer work. The estimating and projecting was done by Mike Staren, who was at that time the boy wonder of SSI.

I had the opportunity to recruit people on my own for the first time and I think the first person I recruited was Lenna Kennedy, who I had worked with in the Disabilities Study Section when I first came to Social Security. Her husband had passed. She lived in Arizona and was working in a district office. I brought her back to Baltimore.

We had a strong outfit with really top people and it was a very enjoyable outfit. I think we did a lot of good work, and prepared a number of research papers. It was the first responsibility I had for starting something up, getting a program moving and being in the management group of ORS. In other words finding out what was going on. A major reason for being a manager, other than the grade, is to find out what's going on, because before that, I wasn't really in on what was happening. I understood what we were trying to do overall and it was a very satisfying experience being in the Division of Supplemental Security Income Studies.

I think career-wise it was good because I was appointed to a GS-15 position sometime in the latter part of 74. We went along and I think the division did fairly well. The SSI program however foundered badly.

Interviewer:

-

Before we go into that, could I just ask, I assumed that you and your group were responsible for the creation of lots of statistical reports that we are still familiar with today. The various SSI reports that we get on state and county, you developed those reports at that time?

Schmulowitz:

-

Yes. We developed the data that we still use, the Revised Management Information Accounting System, is the major data base. We also developed a one percent sample data base.

Interviewer:

-

We still use those today.

Schmulowitz:

-

We still use them today, but after I leave I think they should revamp the thing and take a new look at it because anything that has been running for twenty years should probably be stopped and looked at again.

Jim Callison left in the mid 70s, 76 or 77, and that was a very sad time. Then Tom Staples, who had been a special assistant to Jack Carroll, who had replaced Mrs. Merriam as head of the Office of Research and Statistics, became director and he was really good. He is now Deputy Associate Commissioner for the Office of Financial Policy and Operations, I believe.

After Tom Staples, Dave Podoff became Division Director for a while and then things went poorly. Tom Tissue had a stroke and left government service and Buzz Goldstein, who was in charge of computer work for the division, had a heart attack and then had another kind of heart complication and he retired and died a year or two later. The place was never quite the same as it had been before. We're in the period 79-'80 and the SSI division still has a lot of steam, but it doesn't have the steam it had when Tissue and Buzz were there and when Callison was running it.

Interviewer:

-

In those early days of SSI when the program was kind of foundering, did ORS play any role in supporting the program and trying to get the program organized other than creating these basic reports and the data base?

Schmulowitz:

-

It was a difficult period and I think they made a mistake in the appointment of the first director of the SSI program. They appointed a fellow who didn't know that much about it and was an outside person. Social Security is like what Mayor LaGuardia used to say about himself in New York, when I make a mistake it's a beaut. Would it have been better if someone else had been appointed? It couldn't have been much worse.

A part of it was the institutional nature of Social Security. When Social Security was taking the programs from the States it didn't go all that smoothly we had a poor director situation. The Social Security field staff was not emotionally equipped to handle a welfare program. I was still one of the few social work types in there with welfare experience. I remember talking to district offices and they'd say "what do you do when a client comes in and says blah, blah, blah." I'd say it doesn't bother me, they used to say that to me all the time. And they'd say, "well it bothers me, I don't think people should be talking that way." When you have a welfare clientele they're a little more emotional and get upset and may use obscenities now and then.

Social Security was equipped to handle the aged part, but the aged part soon became a very small part of SSI. We began with two million aged people and twenty years down the line we still have two million aged people. Whereas the disability population grew from a million or so, when we took it over, to four million. I feel the field Staff just couldn't handle it in the sense that they like the idea of people coming into the office and waiting their turn and telling their story and being listened to and being treated respectfully and treating the workers respectfully. I think Social Security had, the leadership problem, that was a given, and behind that was a problem of the field people not really being equipped to handle it. And then I think the Field Staff became angry at Central Office and said this is what killed Social Security.

They gave us the SSI program and it was terrible and became the tail that wagged the dog. It took a while for the SSI program to get off the ground, but I think by 75 or so it was running fairly well. It was running as well as it was going to run, and I don't think we did that bad a job after we got over the shaky period, the first couple of years.

Interviewer:

-

Can I ask you about that early period in SSI, you mentioned that in the field they had difficulty adjusting to this new type of program that we were taking over. Did you see any of that same sort of difficulty here at headquarters and the management aspect of it?

Schmulowitz:

-

No, except they had poor management to start with and then they began to replace it and got regular management type leadership.

Interviewer:

-

So it wasn't a culture shock for the headquarters and the regional offices?

Schmulowitz:

-

No. For us it was the same as it was before. We had data bases and paid checks out and got pieces of paper in and sent pieces of paper out. There was no difference in developing a research program for SSI, then developing a research program for Social Security. You use data bases and analyze data. The shock was in the district offices handling what they considered unruly clients, and which I considered not unruly clients, because they were less unruly than AFDC (Aid to Families with Dependent Children) clients, less emotional, but the district offices became angry because they were handling people who were drug addicts and alcoholics and they felt they were very difficult. And they always are, because they misspend their money and they do the wrong thing and they get arrested. I think the culture shock in the field was very difficult, but I think eventually the field got used to it. I think grudgingly, because I never heard a field person say I'm glad we had the SSI program. On the other hand, in central office, we were glad we got the SSI program because it was more work and more opportunity to prove yourself and promotions, like Medicare.

Medicare was terrific for the Agency. When Medicare came in it helped us solve the civil rights problem because we had all these appointments to make. When the Medicare program came in, between 1965 and 70 we were able to appoint a substantial number of black people to positions through promotions, all over the Agency not just in Medicare. People left one part of the Agency to go to Medicare so promotions and appointments were available all over. Since it wasn't a zero-sum kind of thing, when we appointed black people to positions we weren't taking away from white people. There were promotions and new appointments to go around and it really gave Social Security the opportunity to solve its internal problems. Medicare was exceptionally fortuitous.

In addition, the whole country loved Medicare. From the day Medicare started the old people were enthusiastic about it. It became their program and they liked the idea of the way it worked with the deductibles and the premium payment. You went and when you got your bill, it was in large part paid. You paid the provider what you had to pay. The only thing I heard people complain about was that it was complicated to fill out the forms, but when the program began it was instantly popular. I think even today, with its financial problems and everything else, it's difficult to cut the Medicare program. A lot of it is the people really like the program and it has become part of the culture of the United States. You can see the doctor, get complicated procedures done and not have to pay all that much.

But SSI, for Central Office, administratively, and from a management point of view, was good for the Agency. It created new opportunities, chances to hire new people, chances to promote them, which was not bad at all.

We began, as a division, to run down a bit in the late 70s, and by 1981 the Administration changed. The Reagan administration came in and there was talk that we had too much invested in statistics and research in the government as a whole. With that investment in statistics and research they began to think in terms that ORS itself was perhaps somewhat ineffective, didn't meet current needs. The research wasn't in keeping with what was needed and in 83 we had our major reorganization.

But that gets me a little bit ahead of things. I want to go into something that, while I was in the SSI division, got me into the work that has been very important and that I did for the rest of my time there. One of the institutions of the Office of Research and Statistics has been the Social Security Bulletin. It was a monthly for years and in 91, as ORS became smaller, we couldn't really maintain it as a monthly. Finally, the Commissioner ordered it to become a quarterly.

With the Social Security Bulletin, we began to put out, in 1955, a compendium of annual statistics called the Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin. There was an advisory committee and the first chairman of the advisory committee in 1955 was Lenore Epstein-Bixby, who was deputy to Ida Merriam for a long time, and one of the major figures in the development of ORS. After that the head of the Annual Statistical Supplement Committee was Al Skolnik.

When the SSI program started, I began attending meetings of the annual supplement committee to present the SSI tables that would be added to cover the program. I began attending the meetings regularly and then in 1977 Al Skolnik passed. We were without a committee chairman for a while. In 1978, Jack Carroll named me as Chairman of the Annual Statistical Supplement Committee.

The supplement, like everything else through the years, had become sort of moribund. By 1978 we hadn't published the 76 supplement yet. We used to have a convoy system for publishing. We wouldn't publish the volume called the 76 until all the tables for 76 were available, which could be as late as 78 or so. We didn't publish the 76 until 78 and I became Chairman in 78 and proceeded to reorganize the Supplement and try to get it more on time by taking it off the convoy.

I began adding material to it. The Annual Supplement Committee was made up of people from all over -- SSA ans non-SSA agencies. I guess I engaged in a little packing and got people who thought my way, to go on the Supplement Committee. I had sort of a majority on it and was able to put across my changes to the Supplement with the help of some people. Some people who didn't like what I was doing, dropped out. Those of us that remained had more control of it.

I think we really began to work toward making the Supplement the encyclopedia kind of compendium of the status of the social welfare programs in the United States. We concentrated, of course, heavily on Social Security and SSI, but increased our coverage of the other programs, Medicare and AFDC and began to have written material explaining the programs and giving detailed descriptions of how they worked. Slowly we built it into the kind of massive thing it is today. We're waiting for the 95 edition to come out, which will be at the end of this month and it's going to be something like 410 pages.

Interviewer:

-

So that expansion of the supplement to include the other programs and to be, in effect, a comprehensive compendium was a policy that you implemented?

Schmulowitz:

-

I initiated it, with the people that I got on the committee. Then the people who felt that it should remain primarily focused on Social Security data, which I considered to be old fogies, they more or less dropped out, which was not intended, but wasn't all that bad.

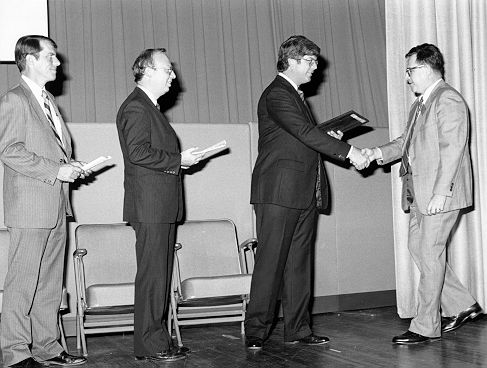

That was very successful and in 1981 Jack Carroll, who was the Associate Commissioner, recommended me for a Commissioner's Citation, which Jack Svahn presented to me. That was based on my work on the Annual Statistical Supplement. Again, although the Division of SSI, I think, was running down a bit at that time, the Supplement sort of took my interest to some extent, because that was on the way up.

Then in 81 or 82 there was a growing tension between the management of ORS. In 1978, under Stanford Ross' reorganization, ORS was put under the Office of Policy, and was pushed down a peg because it no longer reported to the Commissioner directly, but through the Office of Policy. Consequently, ORS no longer had a tie with the Commissioner, who at that time was Stanford Ross. Larry Thompson became head of the Office of Policy under Stanford Ross. There was tension then, I thought, between Larry Thompson and Jack Carroll, who was the head of the Office of Research and Statistics. That didn't change the outfit much, but when the administration changed, when Reagan came in, I thought there was a growing tension between the people managing Social Security at that time and Jack Svahn and the group that came in with him, between them and Larry Thompson and Jack Carroll, a feeling that ORS was too big.

We had been a large outfit, but in 1977 the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) was formed as an independent agency. HCFA received 150 people from ORS since ORS had a large health insurance division, which went over to the new HCFA. However, people still thought that ORS was too big an outfit, 300, 350, maybe 375 people and that we were not all that effective. We did what we wanted to do and we weren't listening to the needs of the Agency.

Then in 83, not as a complete surprise, but as a surprise, the reorganization of ORS was announced. As a result of the reorganization, we lost the program divisions. The Division of Disability Studies went over to the Office of Disability, the Division of SSI Studies went mainly over to the Office of Supplemental Security Income. Larry Thompson by that time had become Director of the Office of Research and Statistics and Jack Carroll had become deputy. Thompson negotiated to retain some people and myself, even though the division went over with Mike Staren, who was the Branch Chief, to head up the SSI research effort in OSSI and a good part of my branch left. Thompson had negotiated that I would stay with ORS, because of my work on the Supplement and that ORS would still be in charge of SSI statistics, to some extent. At least the statistics for the Supplement publication. I ended up keeping a certain number of people in, what was the SSI Analysis Branch, and Survey Branch which went over mainly to OSSI. I think I was the only Branch Chief from the old division that remained.

We didn't have a disability division anymore in ORS. We didn't have most of the SSI division, the RSI division also went over, with certain people staying to do what was considered overall type of work on social welfare programs and workers' compensation. It was a smaller ORS with about 120 people left, which is about the size it is today.

The question was, how do we reorganize ourselves? I had a plan for reorganization of ORS in Baltimore. We would consolidate the statistical group. My plan included SSI statistics and Retirement and Survivors statistics, which were then part of the Division of Statistics in Baltimore, and also included computer work and employment statistics. My plan was essentially, since we were thrown back on a limited kind of function, we should centralize the statistics and make every effort to improve technically the quality of statistics and their timeliness. I convinced Larry Thompson and Jack Carroll that a division should be formed made up of the SSI statistics people, that I was then in charge of, and that the two branches that did OASDI (Old-Age, Survivors & Disability Insurance) statistics and the employment/earnings statistics also be brought in, and a new entity formed. That was done in 83 on a tentative basis, and in 85 became permanent.

I emerged as head of the Division of Statistics Analysis which contained the three branches. We organized the statistics of Social Security and stopped working with the one hundred percent files produced by the Office of Systems (OS), at our specification. It took a long time to produce them and if OS made a mistake you couldn't get them run over. In 81 we were basically without statistics on the Social Security program because OS made a mistake and didn't want to run the files over again.

We began to use sample data bases, one percent samples and ten percent samples and small one hundred percent files. We developed data bases we could manage and access ourselves in ORS from the mainframe using our personal computers. We ended up revising the statistical program of ORS so that most of our statistics were done in house, within ORS, using sample data bases that we could manage ourselves. All that we depended on from the Office of Systems was to provide us once a year with a data extract and we did everything.

Interviewer:

-

While we are on these organizational issues there is one thing that always puzzles me and I'm not quite clear about, and that's the relationship between the ORS organization in Baltimore and the one in Washington. It seems like there has always been these two locations and that has continued throughout this whole period that we're talking about. Can you explain a little bit about the relationship through the years of those two?

Schmulowitz:

-

The Washington outfit had the major intellectual strength of ORS, because they had the Economics Division, which was a strong division, and always has been. Mrs. Merriam was there and Lenore Bixby, as well as, Dorothy Rice and Mollie Orshansky. The brain power to a large extent was in Washington.

In Baltimore I thought we had a reasonable amount of intellectual ability, but we didn't have the degree holders. We didn't have as many Ph.D.s and we didn't have as many people with masters degrees. Also, we allowed other people to be placed. We accepted placements from other outfits when people didn't work out there.

We ended up, from the Baltimore point of view, feeling we were treated colonially. We were looked down on. And Washington people felt we were treated quite fairly because we just didn't have the intellectual resources to match theirs, which was true too. There was always a strained relationship between Baltimore and Washington and now and again it would break into the open, but it was contained.

When the breakup of ORS took place in 1983, it affected both places. Some of the people in the Washington outfit had to move to Baltimore.

In 1975 there was a plan to combine the Washington and Baltimore outfits. At that time there was a vacancy in one of the office buildings that the federal government had used in the Prince George's Shopping Center in Hyattsville, Maryland, where there were three or four office buildings. There was a vacancy and there was an attempt to move the Baltimore ORS to Hyattsville, and move the Washington ORS to Hyattsville. Then ORS would be together as one outfit. At which point, a number of us who didn't want to move to Hyattsville or commute to Hyattsville--I don't drive so it would have been quite difficult for me. I would either have to move to that area or arrange for train transportation. I was probably the instigator who organized to prevent the move.

There was an obscure law which prevented the move. No one was aware of it. In 1953 when Social Security was planning to build the Woodlawn facility, the Congressman from my area in northwest Baltimore, Sam Friedel, was fearful that the then Secretary Mrs. Hobby would move part of Social Security to Washington. They would move the staff and professional outfits in Baltimore to Washington, the research, budget and so forth. the budget and so forth. In the appropriations bill of 1953 there's a provision which says that the headquarters of Social Security, then the Bureau of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance shall be in Baltimore, Maryland. This meant that staff components couldn't be moved from Baltimore to Washington. You could move individual people, but you couldn't move components.

(Ed. Note: This provision was in the Supplemental Appropriations Act of 1955, which became law on 8/26/54.)

We based our appeal against the proposed move on the Friedel Amendment. As far as I know that amendment is still in effect, and you can't move staff components to Washington. I think you can move individuals, and people can go voluntarily. We had a small letter writing campaign to the congressman from the Baltimore area and to Senator Mathias (Senator Charles McC. Mathias) the Republican from western Maryland. He was sort of a moderate liberal Republican. We pointed out the Friedel Amendment and then the commission backed away. We never did move together. Of course we understood, the Washington people didn't want to come to Baltimore, they didn't want to give up their homes and move to Baltimore and we didn't want to go to Washington.

Interviewer:

-

Now did that change at all after the 83 reorganization or was it just a case that both organizations were reduced in size?

Schmulowitz:

-

Both were reduced.

Interviewer:

-

Did the relationship stay the same?

Schmulowitz:

-

The relationship stayed the same. Washington still had more of the intellectual strength of the outfit. Baltimore felt that they were being disrespected and that kind of tension has remained. It may have eased a bit because in the last few years the directors of ORS have not been ORS people, initially. Peggy Trout was acting director, Mike Johnson was acting director, Peter Wheeler came in as Director or Associate Commissioner, but they were all from Baltimore to start with. It wasn't that management was always in Washington. That has eased it a bit, but I think the tension is still there.

1983 was a dramatic time for ORS. All our friends went to other places and began new careers and separate development from us.

The people I worked with, and myself, felt this is the time to work on improving what we are doing, get a better product out and make the product more accessible and not worry so much about the big research picture. And also take under advisement what the 83 reorganization told us. Make yourself a little more useful to the Social Security Administration and a little more amenable to direction. It appeared, that we did our own thing and weren't conscious of the problems Social Security was having. I think in Baltimore we really tried to improve our statistical presentation, provide advice to people outside ORS about how to do their own statistics and how to do their own research and small studies.

It was a difficult time. Jane Ross was the director. We were also knocked down from being an Associate Commissionership. We were under the Office of Policy, which had an Associate Commissioner, and we also had the indignity of a name change. We lost ORS and became ORSIP, and the name rankled everyone, the Office of Research and Statistics and International Policy. What does international policy have to do with research and statistics? I think Jane Ross was Deputy Associate Commissioner for a while and she was moved out of that and left the Agency. She became a major figure in GAO, studying Social Security disability problems. Larry Thompson had to leave and he went to GAO and became the deputy there. John Hambor, who was head of the Economics Division, became director after Jane Ross left. I think he was uncomfortable with it, because he left and went over to the Treasury Department. He's now the head of the tax policy office there. Larry Thompson came back when the Clinton people came in.

I think the period in the 80s was difficult for ORS. We were much smaller. People didn't think we were still the right size, that we should have been smaller then we were. We were attempting to reinvent ourselves and try to be more pragmatic. At least that's what my colleagues and I tried to do in Baltimore, and be as helpful as we could, and as inconspicuous as possible.

Interviewer:

-

Now another thing that was happening in the Agency in the program in the early 80s is of course all the turmoil around disability and around continuing disability reviews, the CDRs. I take it that some research work was done there, were you involved in any of that disability research around that time?

Schmulowitz:

-

No I wasn't involved in the research. We had the disability division, before the reorganization, and they did work on the CDRs and especially on the court work, the appeals process. And ORS did some good work on that. On the other hand, we were not to aware of the major mechanism of the change that was done in 81 to reduce the disability rolls. We were in some ways out of the loop.

I don't know if you recall the 81 period. What Jack Svahn wanted to do was, he felt and the administration felt, that the disability rolls were overblown. The legislation in 1980 had sort of said that something should be done. And he changed the rules of doing continuing disability reviews to a de novo concept. Generally, the rule in Government is that in order to make a change you have to show how the situation today differs from what it was yesterday. We assume that you got on the rolls legitimately. If you got on the rolls legitimately SSA has to prove that you got better from that point of view. Savhn felt that this was not fair, that the continuing disability review should be a de novo review. If you're not disabled today SSA doesn't have to see how it differs from before. Now that was not done by regulation. He did it by going into the Commissioner's rulings and doing it as an instruction to the staff. That it was his opinion that CDRs should be done de novo.

Under that cover, under that rule, a substantial number of people were removed from disability rolls from 81 to 83. There was a terrible outcry about it and in 1984 Congress reversed it and said CDRs have to be done on the basis of proving improvement. They said SSA had to develop new mental health regulations that were more in keeping with current mental health thinking. It was really a big push against what we had done in 81 to 84.

We brought in a new Associate Commissioner, Pat Owens, to head the Office of Disability. She arranged for a contract with the American Psychiatric Association to help us rewrite the mental health regulations. The net effect of it was, it probably went too far the other way. We've got the new legislation and regulations and then with the more favorable way the courts have looked at the problems of children under SSI, the Zebley case, we really had this big growth in disability caseload.

Interviewer:

-

Let me ask you about two particular studies and if you have anything to comment on either of these studies. One of things that happened in that early period of the CDRs is that we did some kind of a program to target CDRs on people who are likely to be recovered. So that, instead of taking a random selection of who was going to be reviewed, we developed some kind of statistical profile that we used to target likely cases, which on its face seems to be a reasonable management maneuver, but the net result was that the rate of people being taken off the rolls was very, very high at the start of that process because we were targeting folks, and that issue became a controversy in part of this history there. Do you know anything about that study or have anything to say on that?

Schmulowitz:

-

My feeling is that most of the removals from the disability rolls were based on de novo, and targeting was based on, it was easiest to establish that people were more or less symptom-free in mental health cases, where they actually were not. Generally, in disability you were eligible if you weren't working for six months and were in a mental hospital and had a psychiatric diagnosis. On the other hand, with all the psychotherapeutic drugs, when they came out of the hospital people on medication seemed symptom-free. Most of the removals were done on the basis of de novo review. Targeting was part of the de novo review. A lot of people on the outside felt that the targeting was discriminatory and was not a valid management tool, when taken together with de novo review of the CDRs. We ran into tremendous opposition on the outside, and then Congress followed. That whole period was a low point. I think a great deal of the feelings against Social Security, on the outside, the advocacy communities and mental health people, were based on the idea that we had become the bad guys.

Interviewer:

-

Now there is one other study I wanted to ask you about and it's sort of related to this issue of how you do sampling and targeting reviews and so on. This was a thing called the Bellmon Review.

Schmulowitz:

-

The Bellmon Review was a good study. It was done by the disability people and this was one of the studies ordered by 1980 legislation. I believe it was mostly directed at how the hearings were working out. That was not part of this negative thing at all.

Interviewer:

-

As I understand it, a similar complaint was raised by the Administrative Law Judges, who argued that the Bellmon Review, because the samples appeared to target ALJs with high reversal rates for review, this is the allegation, was prejudicial against allowance rates and so on. Is that the case?

Schmulowitz:

-

Again, the tensions between the ALJs and the Agency are of long-standing duration. Out of all the work of the early 80s the reaction was, a dramatic increase in the use of attorneys by disabled claimants. I recently studied attorney fee cases and in that year we had 140,000 people who won awards with an attorney. We paid attorneys $340 million in fees. People began to feel that they had to go to an attorney to win their case at the hearing level. The hearing level reversed, maybe it will change with the reengineering process, a large portion of our denials. We felt that we had no control over the Administrative Law Judges, that they were not operating according to the same rules we were. They felt we were misreading the rules and that they were operating reasonably. The net effect has been that the Administrative Law Judges were given greater independence and autonomy, and the clients win more cases.

Data for 1994 shows that half the people who are awarded disability benefits, get on for muscular-skeletal problems, back problems, orthopedic problems and so forth, that half the people in a year who are awarded with this diagnosis are allowed at the hearing level. Forty percent of the hearings cases are muscular-skeletal problems.

This long term problem is not near solution. It's the major thing tackled by disability reengineering. They're trying to get a way to handle the disability cases more fairly and more expeditiously at the initial level, so not that many cases have to go to the hearing level. And the decisions at the hearing level will not differ that markedly from the decision at the initial and reconsideration level. I don't know where the disability reengineering will go finally. It could lead, hopefully, to fairer more prompt decisions at the lower levels. I can't believe that it's good, that so many people who file for disability have to go to an attorney, pay thousands of dollars in fees, the average fee is $2,500, and a large chunk of the fees are at the maximum $4,000. You can go higher than that because you can get special fees approved by the ALJs, which many judges do.

The whole ALJ conflict with the Social Security disability determination process has to come to an end. I think it will under the disability policy reengineering. One of the goals, obviously the major goal, is to get a fairer decision made in a more reasonable length of time, that people shouldn't think they have to fight all the time to get Social Security benefits. This should bring a resolution to the conflict between the ALJs and the rest of the Agency.

I think there's justice on both sides. It seems you can win a case at the ALJ level. However, the people are represented a good deal of the time by attorneys. The attorneys seem to marshal medical evidence better, which is the attorney's major job in any kind of disability work. I think Social Security would like to close cases at an early level to prevent bringing in evidence gathered later. On the other hand, ALJs are saying people get sicker during the process, because the process takes six months to a year, and there's nothing wrong with bringing in the latest evidence. I think that disability reengineering is our only hope of getting some kind of settlement of the disability problem. The clients experience long waits for benefits, and feel that they had a hard time. The rolls keep getting larger and I think the disability problem has replaced everything else in Social Security as our major concern.

The disability problem, I think, was exacerbated in the early 80s by trying to prepare the rolls too rapidly. Certainly, I think the attempts to skirt the issue, the regular procedure for issuing regulations, and moving too fast on disability was, and then going the other way with the 84 legislation produced unfortunate results. We ended up getting back numbers of people who were thrown off, with large retroactive settlements and with everyone in the client population adopting sort of a confrontational attitude.

Disability has certainly run downhill in SSA, the last ten years. It's really a very serious problem and I hope the disability reengineering process is successful. I like the fellow who is running it, Chuck Jones. I think he understands it and will try to work out a reasonable arrangement for all parties.

Interviewer:

-

Let's go back to your chronology where we were in ORS in 1984, and bring us up after 1984. What happened next?

Schmulowitz:

-

In 84 Jane Ross went up to become the Deputy Associate Commissioner and then was removed. Then Mike Hambor, who was the ORS director after Jane Ross, felt he had to leave. We had a period of acting directors starting with Mike Johnson. Afterward, Peggy Trout was acting for a while. Pete Wheeler came in September of 92 with a permanent appointment. We got our name back as the Office of Research and Statistics. They stopped this ORSIP stuff. We're no longer under the Office of Policy, we have an Associate Commissionership and we report directly to a Deputy Commissioner again. It looks like things may be back on the up-swing.

Currently, a small number of components that were under the Deputy Commissioner for Programs and External Affairs, has now expanded and now taken in the program and policy components. They are working currently on a policy area reorganization, which may end up with bringing people back into the ORS who had left earlier.

Actually, the up-swing dates from Gwen King's coming in as Commissioner. I think Gwen King really believed in the idea that President Bush had expressed of a gentler, kinder America. From the time Gwen King came I felt better personally and began to work on minority statistics again. I started to develop a new data base for getting minority statistics in better shape, to cope with our enumeration at birth policy, with our classifications, and data base problems.

I felt a change in that the time was more amenable to research and statistics within the Social Security Administration. It seemed to get a little better, and currently this trend may continue.

We have two major research outfits that we had in ORS before that are now outside of ORS, Baltimore. They are both now in the Office of Program Benefits Policy because that combined old ORSI and old OSSI. In OSSI there's the outfit which is the old SSI division (ORS), except for the few of us that stayed behind. The old SSI division was much expanded by OSSI. On the other hand the leader of that group, which was a major branch in the old division, Mike Staren, passed several years ago after a long illness. The place doesn't have the intellectual strength it had before. Don Rigby, who was another Branch Chief in the old ORS group, retired last year. I think that there's consideration being given to that group rejoining ORS. In the Office of Disability, the old ORS disability division, which went over, has stayed there. We brought some of the people back to ORS a while back. We have a small disability group from that division, but basically the division is in the Office of Disability (OD) under Alan Shaffer.

They have many a lot of responsibilities through demonstrations and outreach work, and Project Network is sort of in their area. They've built a strong data base outfit. They did substantial work supporting the recent studies for the disability research initiative preparing data bases. If that group is brought back to ORS and the former OSSI group is brought back, ORS will of course be in size and importance, where it was before. If it's not brought back, if only one of the two would be brought back, it would probably be the OSSI group and the OD group may stay with OD.

I think that, in general, research and statistics prospects are somewhat better that they were in the 80s, though I don't think we'll ever have the standing in the Agency we had in the time of Ida Merriam. I don't think we can approach that level and probably the Agency's too amorphous for that kind thing. And I don't think we have that type of person on the horizon, an Ida Merriam or Dorothy Rice type to run it. Even if we did, they could obtain that kind of position. I look for ORS, having made progress in the last few years, to move ahead somewhat in the future, certainly better then they were in the 80s. Larry Thompson, our former leader, still the Commissioner's right hand person, is I think quite favorably disposed. Shirley Chater has said one of her major goals is to revitalize research and statistics.

This brings me to the end of my own time in ORS. As we finish this year I will have been the chairman for the 16th Annual Statistical Supplement. There were only twenty-two others besides the sixteen. And having gone through six issues of our explanation of what the social welfare structure in the United States looks like, Social Security Programs of the United States, which I coordinated. I had twelve years of that, six biennial issues, including the projected 1995 version.

At this point I think it's time for other people to take a crack at this stuff and have the responsibility without having many of us looking over their shoulders. We've had a very large leaving of the old guard in ORS in the current wave of buy-outs and lump sums. We lost the division director of the Division of Statistics, Warren Buckler. Two grade fifteen's, who had formerly held major positions also retired. Barry Bye, who did the Bellmon Study and who has been deputy in the Statistics Division left. In Baltimore it will really be a complete turn around and will give the people who have not had a chance to show their wares, a chance to show them.

Perhaps without us there, they will be more prone to come forward with new ways of doing things. If you're doing the SSI statistics this way for twenty years, if you're doing the Supplement this way, maybe we need to change something. Because while I was there, and while Barry was there and while Warren (Buckler) was there, it was difficult for the other people to say "lets throw this stuff out, it's not all that good." I believe change should take place and part of the way of change is the people in charge moving out. Otherwise it's very difficult to put changes through with the old people still in charge. You get quite dogmatic as you get older.

Here I am receiving my Commissioner's Citation from Jack Svahn, I guess that is. Who are the other two?

Interviewer:

-

The fellow on the left is Paul Simmons, who was Deputy Commissioner. . .

Schmulowitz:

-

Paul Simmons, passed a few years ago.

Interviewer:

-

I don't recognize the fellow in the middle.

Ed. Note: The picture depicts Jack receiving his Commissioner's Citation from Commissioner Jack Svahn. Also shown, left to right, Paul Simmons, SSA Deputy Commissioner for Policy and External Affairs, and David Swoap, HHS Undersecretary.

This is a picture of an award presentation to Phyllis Marbray, the third one over, (from the left) from the Publications Staff, who is the editor of the Supplement. This was her DCPEA (Deputy Commissioner for Policy & External Affairs) award and next to her is her supervisor, Marilyn Thomas, Chief of the Publications Staff. I'm over on the side there. (See photo)

Interviewer:

-

Let me ask you one last question just for the interview, and give you a chance to sort of give your overall assessment of your career of thirty-four years with Social Security. How do you assess it Jack? What's your impression?

Schmulowitz:

-

Well, it certainly exceeded my expectations. I was able to accomplish a good deal. I met my career expectations more than I thought I would.

I guess afterwards I thought, how is it that I was not selected for an SES, but I wasn't slated to be an SES. I consider on a personal basis, it was a good career. I've been a grade fifteen since 1974, supervisor for twenty-one years. I feel it has been very satisfying. I was able to do the kind of work that I had always wanted to do from the time I went to work for the Welfare Department, study the social welfare institutions of the United States.

I was always, what would be called today, the high school nerd. I liked to read, I liked to study. I've been able to do for a living what I enjoy doing, which is to be a student. I've been able to study the social welfare institutions of this country, monitor their progress, write about them, do statistics, analyze them, analyze specific problems that existed in the program and the agencies.

The last few years have not been the best for social welfare institutions. I think social welfare is in for a period of slow down. Looking at it overall, when I came here, public social welfare expenditures were twelve percent of the gross domestic product, today they're twenty-one percent. There was much less commitment in 61 than today. Now people feel it may be too much of a commitment.