Commissioner, Social Security Administration

before the House Committee on Ways and Means,

Subcommittee on Social Security

March 20, 2012

Chairman Johnson and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for this opportunity to discuss our disability programs. They are a crucial part of America’s safety net. Through these programs, we provide vital support to some of the most vulnerable members of our society. Today, I will discuss how the definition of disability has changed over time, how we evaluate disability claims, the role State agencies play in the disability claims process, and a legislative proposal in the President’s current budget request that would restore Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) demonstration authority and initiate a pilot project to simplify return to work rules.

Introduction

Under the Social Security Act (Act), we administer two major programs that provide cash benefits to persons with disabling physical and mental disorders: the SSDI program and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. The SSDI program provides benefits to disabled workers and to their dependents and survivors. Workers become insured under the SSDI program based on contributions to the Social Security trust funds through taxes on their wages and self-employment income. Under the Act, most SSDI beneficiaries receive Medicare after being entitled to cash benefits for 24 months. SSI is a Federal means-tested program funded by general tax revenues designed to provide cash assistance to aged, blind, and disabled persons with little or no income or resources to meet their basic needs for food, clothing, and shelter. Last fiscal year, our programs provided an average of about 15 million beneficiaries with a total of approximately $175 billion in benefit payments.

These programs have grown in both complexity and the number of people who depend on them. Over the last five years, we have improved the disability process despite the huge influx of new disability claims that has strained our limited resources. We have met new program and administrative requirements at minimal cost to the taxpayers. Our overhead is approximately 1.5 percent of all the benefit payments that we make. During my time as Commissioner, we have faced several extraordinary service delivery challenges. The aging of the Baby Boomer population affected us in two ways: we saw an increased workload, and we lost our more experienced employees to retirement. We have seen an increase in initial disability claims of about 25 percent during the economic downturn.1

For FY 2013, we are requesting $11.760 billion for our administrative expenses, a modest increase from FY 2012. I urge Congress to pass this level of funding because we have proven that we deliver. We have drastically reduced the time claimants wait for a hearing decision. In FY 2011, we cut the average wait below one year for the first time since 2003. Wait times were also down in field offices and on our 800-number. Busy signals on our 800-number were the lowest ever. Through the hard work of our employees and technological advancements, we have increased employee productivity by an average of about four percent in each of the last five years. Few, if any, organizations have accomplished similar improvements.

We achieved these improvements even as we have steadily increased our program integrity work as well. Since 2007, we have doubled our Supplemental Security Income (SSI) non-disability redeterminations and increased our medical Continuing Disability Reviews (CDRs) by over 80 percent, and we will conduct even more reviews this fiscal year. The benefits we save through these efforts far outweigh their costs, and we have seen a significant increase in SSI payment accuracy. The Administration strongly supports the program integrity cap adjustments authorized by the Budget Control Act, which would put Social Security on a ten-year path to eliminate the backlog in program integrity reviews. The President's Budget requests $1 billion for SSA program integrity in 2013 and calls on Congress to appropriate the remaining $140 million in program integrity funding authorized under the BCA for 2012.

Despite these remarkable outcomes, in FY 2011 and FY 2012, we received appropriations that were far below what the President requested. Although our annual appropriation increased between FY 2011 and FY 2012, due to rescissions to our information technology account in FY 2012 we are operating with $400 million less than we had in FY 2010. The lower-than-requested appropriation, coupled with the IT account rescissions, forces us to make hard choices so that we can direct our limited resources to our most vital services.

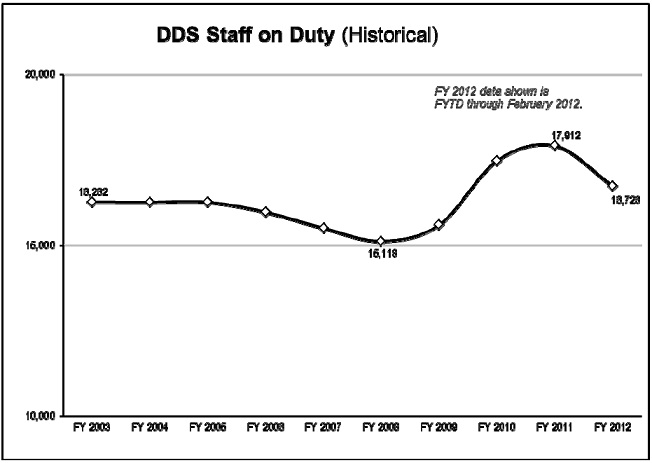

Our FY 2013 budget request is lean. We have already curbed lower priority activities so that we can continue to achieve two of our most important goals – eliminating the hearings backlog and focusing on program integrity work. While we will achieve goals associated with these priorities, we simply cannot do all of the other work we are required to do. We expect to lose over 3,000 employees in FY 2012 and over 2,000 more in FY 2013, on top of the more than 4,000 employees we already lost in FY 2011 – a total loss of more than 9,000 Social Security and State Disability Determination Services employees in just three years. When I leave office in 2013, the agency will have about the same number of employees that we had when I arrived in 2007 even though our work has increased dramatically. Retirement and Survivor claims will have increased by over 30 percent and disability claims will have increased by nearly 25 percent since that time.

In addition to increases in our core program workloads, we offer lesser-known but important services that lead to millions of Americans visiting our field offices or calling us each year. For example, in FY 2011, we issued about 1 million replacement Medicare cards, and handled nearly 1 million transactions in administering the Medicare lowincome subsidy program. Other responsibilities include supporting the Department of Homeland Security’s program to verify new employee hires, for which we handle nearly 125,000 inquiries each year. In fact, if you look at our waiting rooms today, you see very few older Americans. You do see younger Americans, often with children, waiting for a document some other Federal, State, or local agency is requiring for authentication purposes. It could be a replacement Social Security card or a benefit verification; we handle about 25 million requests for these documents each year. Together, we need to figure out how to build upon our successes in light of these challenges.

Definition of Disability

For both the SSDI and SSI disability programs, the Act generally defines disability as the

inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) due to a physical or mental

impairment that has lasted or is expected to last at least one year or to result in death.2

Under this very strict standard, a person is disabled only if he or she cannot work due to a

medically determinable impairment. As the Committee on Ways and Means noted in its

report that accompanied the Social Security Amendments of 1956, even a person with a

severe impairment cannot receive disability benefits if he or she can engage in any SGA.

Moreover, the Act does not provide short-term or partial disability benefits.

Let me emphasize that the Act uses a specialized definition of disability developed over the years by Congress to address the stated statutory purposes of the SSDI and SSI programs. The Act’s definition of disability would not be suitable for other Federal programs with different purposes. Under SSDI, insured workers who become disabled receive monthly benefits based on their past earnings. In contrast, the Department of Veterans Affairs provides disability compensation to veterans based on the severity of disabilities resulting from injuries or diseases incurred while on active military service, or were made worse by active military service; furthermore, veterans may receive benefits for partial disability. This specialized standard for Americans who have sacrificed their health for the good of the entire country is appropriate for the specific circumstances they are intended to address.

To provide a more complete understanding of our definition, I will sketch the history of its development.

1950s

Congress first defined disability in the Social Security Act Amendments of 1952. This law applied to workers who were either blind or unable to engage in SGA because of any medically determinable impairment, which could be expected to be permanent. The law did not provide cash benefits to disabled workers but instead protected their ability to receive retirement benefits. Retirement benefits are computed based on earnings; therefore, a disabled worker with a “period of disability” could have experienced reduced or no retirement benefits due to his or her lost earnings. The 1952 amendments established the concept of a “disability freeze,” under which we could exclude a disabled worker’s periods of disability when calculating his or her retirement benefits. However, as enacted, the law expired on July 1, 1953, and did not allow a person to file a claim until after June 30, 1953. It was essentially non-operative.

Two years later, the Social Security Amendments of 1954 created the first operational Social Security disability program; it instituted the disability freeze for workers who met the law’s definition of disability. The 1954 law defined disability as blindness or the “inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity by reason of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment which can be expected to result in death or to be of long-continued and indefinite duration.” Other than a slight change in the durational requirement, this definition did not differ from the 1952 definition.

Congress established the payment of cash benefits in the Social Security Amendments of 1956. To be eligible for cash benefits, the legislation defined disability to also require that the claimant had to be between the ages of 50 and 65, complete a 6-month waiting period, and could not qualify on the basis of blindness. The Committee on Ways and Means reported:

[R]etirement protection for the 70 million workers under old-age and survivors insurance is incomplete because it does not now provide a lower retirement age for those who are demonstrably retired by reasons of a permanent and total disability.3

It is important to remember that during the debate on the 1956 amendments, some

opponents of this legislation argued that Congress had not properly assessed the future

cost of providing disability benefits. In response, the legislation’s supporters argued that

the very strict definition of disability and other features of the new program would ensure

that it would remain financially sound.

1960s and 1970s

The Social Security Amendments of 1960 removed the minimum age requirement (50) for receiving disability benefits. Congress then changed the durational requirement from "long-continued and indefinite duration" to "expected to last for a continuous period of not less than 12 months" in the Social Security Amendments of 1965.

In the Social Security Amendments of 1967, Congress adjusted the definition of disability to clarify when a person is considered unable to work due to impairment.4 Specifically, Congress supplemented the definition of disability to clarify that:

[A]n individual . . . shall be determined to be under a disability only if his physical or mental impairment or impairments are of such severity that he is not only unable to do his previous work but cannot, considering his age, education and work experience, engage in any other kind of substantial gainful work which exists in the national economy, regardless of whether such work exists in the immediate area in which he lives, or whether a specific job vacancy exists for him, or whether he would be hired if he applied for work.5

In passing this law, the legislative history indicates that Congress intended to overturn judicial interpretations that effectively made it easier for persons to be eligible for disability benefits.

Rounding out the legislative activity of this period, Congress reduced the waiting period from six months to five months in the Social Security Amendments of 1972. These amendments also created the SSI program, which used the SSDI definition of disability. Congress would not again revise the definition of disability until 1996.

1990s

Between 1989 and 1994, the number of people on disability and program costs increased significantly. In fact, in 1992 the Board of Trustees predicted that the DI Trust Fund would run out in 1997, and urged prompt legislative action.

Congress subsequently held a number of hearings from 1993 to 1995 on the disability program’s rising costs. One issue discussed in these hearings was the increasing number of disability allowances based on drug addiction or alcoholism (DA&A). Congress initially passed legislation in 1994 to limit benefits to beneficiaries with DA&A. However, in the Contract with America Advancement Act of 1996, Congress narrowed the definition of disability to exclude DA&A; a claimant is not considered to be disabled if DA&A is a contributing factor material to the determination of disability.

The Role of Work Incentives

Since creating the disability freeze in 1954, Congress has consistently emphasized the importance of vocational rehabilitation (VR) for disabled persons. Congress has established various work incentives to help disability beneficiaries return to work. These work incentives allow SSDI and SSI beneficiaries to continue to receive benefits while performing some level of work. However, over the years, these work incentives have been difficult to administer and difficult for beneficiaries to understand. They have also complicated the definition of disability.

The Social Security Amendments of 1956 allowed SSDI beneficiaries who were participating in a state VR program to work at SGA for up to one year. This provision was the forerunner to the trial work period (TWP), which Congress originally enacted in 1960 in order to broaden the work incentives offered to disabled beneficiaries. The TWP now allows SSDI beneficiaries to test their ability to work for 9 months over a rolling 60- month period; during the TWP, disability beneficiaries receive full SSDI benefits regardless of how high their earnings might be.

In the Social Security Disability Amendments of 1980, Congress created a 15-month reentitlement period, known as the extended period of eligibility (EPE), for disability beneficiaries who have completed a TWP. Under the EPE, a beneficiary may receive benefits at any time during the re-entitlement period when work activity falls below the SGA level. In 1987, Congress subsequently expanded the EPE to 36 months.6

For the SSI program, Congress took a different approach to removing work disincentives. It created rules for counting income from earnings that were more beneficial to SSI disability beneficiaries. For example, the Social Security Amendments of 1972 created the Plan to Achieve Self-Support. This provision allows beneficiaries to set aside other income or resources for a specified period to pursue work goals that will reduce their reliance on benefits. The Social Security Disability Amendments of 1980 eliminated SGA as a reason to terminate an SSI disability beneficiary’s benefits. Congress added section 1619 to the Act, which provides special benefits to SSI disability beneficiaries who perform SGA.7

I will now discuss the way we apply the definition of disability in order to evaluate

disability claims.

Evaluating Disability Claims – The Sequential Evaluation Process

For both disability programs, we evaluate adult claimants under a standardized five-step evaluation process (sequential evaluation), which we formally incorporated into our regulations in 1978. At step one, we determine whether the claimant is engaging in SGA. SGA is significant work normally done for pay or profit. The Act establishes the SGA earnings level for blind persons and requires us to establish the SGA level for other disabled persons.8 If the claimant is engaging in SGA, we deny the claim without considering medical factors.

If a claimant is not engaging in SGA, at step two we assess the existence, severity, and duration of the claimant’s impairment (or combination of impairments). The Social Security Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984 revised the Act to require us to consider the combined effect of all of a person's impairments, regardless of whether any one impairment is severe.9 Throughout the sequential evaluation, we consider all of the claimant’s physical and mental impairments singly and in combination.10

If we determine that the claimant does not have a medically determinable impairment, or the impairment or combined impairments are “not severe” (i.e., they do not significantly limit the claimant’s ability to perform basic work activities), we deny the claim at the second step. If the impairment is “severe,” we proceed to the third step.

Listing of Impairments

At the third step, we determine whether the impairment “meets” or “equals” the criteria of one of the medical Listing of Impairments (Listings) in our regulations.

The Listings describe for each major body system the impairments considered so debilitating that they would reasonably prevent an adult from working. The Act does not require the Listings, but we have been using them in one form or another since 1955. The listed impairments are permanent, expected to result in death, or last for a specific period greater than 12 months.

Using the rulemaking process, we revise the Listings’ criteria on an ongoing basis.11 When updating a listing, we consider current medical literature, information from medical experts, disability adjudicator feedback, and research by organizations such as the Institute of Medicine. As we update entire body systems, we also make targeted changes to specific rules as necessary.

If the claimant has an impairment that meets or equals the criteria in the Listings, we allow the disability claim without considering the claimant’s age, education, or past work experience.

As part of our process at step three, we have developed an important initiative - our Compassionate Allowance (CAL) initiative – that allows us to identify claimants who are clearly disabled because the nature of their disease or condition clearly meets the statutory standard for disability. With the help of sophisticated new information technology, we can quickly identify potential Compassionate Allowances and then swiftly make decisions. We currently recognize 113 CAL conditions, and we expect to expand the list later this year. We continue to review our CAL policy to ensure it is based on the most up-to-date medical science.

Residual Functional Capacity

A claimant who does not meet or equal a listing may still be disabled. The Act requires us to consider how a claimant’s condition affects his or her ability to perform previous work or, considering his or her age, education, and work experience, other work that exists in the national economy. Consequently, we assess what the claimant can still do despite physical and mental impairments – i.e., we assess his or her residual functional capacity (RFC). We use that RFC assessment in the last two steps of the sequential evaluation.

We have developed a regulatory framework to assess RFC. An RFC assessment must reflect a claimant’s ability to perform work activity on a regular and continuing basis (i.e., eight hours a day for five days a week, or an equivalent work schedule). We assess the claimant’s RFC based on all of the evidence in the record, such as treatment history, objective medical evidence, and activities of daily living.

We must also consider the credibility of a claimant’s subjective complaints, such as pain. Such decisions are inherently extremely difficult. Under our regulations, disability adjudicators use a two-step process to evaluate credibility. First, the adjudicator must determine whether medical signs and laboratory findings show that the claimant has a medically determinable impairment that could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms alleged. If the claimant has such an impairment, the adjudicator must then consider all of the medical and non-medical evidence to determine the credibility of the claimant’s statements about the intensity, persistence, and limiting effects of symptoms. The adjudicator cannot disregard the claimant’s statements about his or her symptoms simply because the objective medical evidence alone does not fully support them.

The courts have influenced our rules about assessing a claimant’s RFC. For example, when we assess the severity of a claimant’s medical condition, we historically have given greater weight to the opinion of the physician or psychologist who treats that claimant. We followed this policy because a treating source usually is the most knowledgeable about his or her patient’s medical condition and is in the best position to assess its severity. While the courts generally agreed that adjudicators should give special weight to treating source opinions, the courts formulated different rules about how adjudicators should evaluate treating source opinions. In 1991, we issued regulations that articulate how we evaluate treating source opinions.12 However, the courts have continued to interpret this rule in conflicting ways.

Once we assess the claimant’s RFC, we move to the fourth step of the sequential evaluation.

Medical-Vocational Decisions (Steps 4 and 5)

At step four, we consider whether the claimant’s RFC prevents the claimant from performing any past relevant work. If the claimant can perform his or her past relevant work, we deny the disability claim.

If the claimant cannot perform past relevant work (or if the claimant did not have any past relevant work), we move to the fifth step of the sequential evaluation. As I will discuss later, we have proposed slight modifications to this rule to streamline the adjudication process. At step five, we determine whether the claimant, given his or her RFC, age, education, and work experience, can do other work that exists in the national economy. If a claimant cannot perform other work, we will find that the claimant is disabled.

We use detailed vocational rules to minimize subjectivity and promote national consistency in determining whether a claimant can perform other work that exists in the national economy. When we issued these rules in 1978, we noted that the Committee on Ways and Means, in its report accompanying the Social Security Amendments of 1967, said that:

It is, and has been, the intent of the statute to provide a definition of disability which can be applied with uniformity and consistency throughout the Nation, without regard to where a particular individual may reside, to local hiring practices or employer preferences, or to the state of the local or national economy.13

The medical-vocational rules, set out in a series of “grids,” relate age, education, and past work experience to the claimant's RFC to perform work-related physical and mental activities. Depending on those factors, the grid may direct us to allow or deny a disability claim. For cases that do not fall squarely within a vocational rule, we use the rules as a framework for decision-making. In addition, an adjudicator may rely on a vocational expert to identify other work that a claimant could perform.

I now will explain the role that State agencies play in administering both of our disability programs.

Disability Determination Services

Our disability process consists of several levels of review. Our partners in the State agencies play a crucial role in our disability claims process. When we receive a disability claim, we generally send the claim to a State disability determination service (DDS).14

We rely upon the 54 State DDSs to develop medical evidence and determine whether claimants are disabled or whether beneficiaries continue to be disabled. We fully fund what it costs the DDSs to make these determinations, including the salary and benefits of DDS personnel. DDS employees are State employees, but States are required to follow our program rules in a consistent and uniform manner.15 There is only one national definition of disability in the SSDI and SSI programs. DDSs generally use a team consisting of a disability examiner and a medical or psychological consultant to adjudicate claims.

If the claimant is dissatisfied with the initial disability determination, our regulations provide for the following three levels of administrative review: a reconsideration by the DDS;16 a hearing before an administrative law judge; and a request for review by our Appeals Council. If the Appeals Council denies the request for review (or if the Appeals Council grants the request and issues a decision), the claimant may appeal to Federal district court. Although it is not the focus of this hearing, the appeals process is an important part of the disability determination process and an area that we have devoted a great deal of energy and resources to over the past five years.

History of the Federal-State Relationship

Our relationship with the DDSs dates back to 1954. At the time, the States already had responsibility for administering vocational rehabilitation programs under the Vocational Rehabilitation Act. Congress tasked the States with determining whether workers qualified for the disability freeze; it reasoned that the States routinely undertook medical and vocational case development and had well-established relationships with medical professionals through the existing vocational rehabilitation programs. We entered into negotiated agreements with the States to administer the disability freeze under criteria and procedures that we established. When Congress created the SSDI program in 1956 and the SSI disability program in 1972, we extended those negotiated agreements to the new programs.

Following public criticism of the lack of uniformity and quality in State disability decisions, Congress ended our negotiated agreements with the States in the Social Security Disability Amendments of 1980. Under that law, Congress instead required the States to make disability determinations in accordance with the standards and criteria contained in the Act and our regulations. The 1980 Amendments also authorized us to issue regulations containing performance standards and other administrative requirements. Congress gave each State the option of turning over the disability determination function to us, and authorized us to assume the disability determination function of any State that we found, after notice and opportunity for a hearing, to be substantially failing to make disability determinations consistent with our regulations and other written guidelines. To date, we have not assumed the disability determination function of any State.

Performance Standards and Quality Review Initiatives

We take our responsibility to be good stewards of the trust funds and taxpayers’ money very seriously and strive to provide the highest quality service possible. We have performance standards and multiple layers of quality review to ensure that the DDSs uniformly and correctly apply our program rules.

Our rules require the DDSs to have an internal quality assurance (QA) function. In addition, our Office of Quality Performance (OQP) conducts QA reviews of samples of the initial, reconsideration, and continuing disability review (CDR) determinations of the DDSs. Between FY 2007 and FY 2011, OQP reviews showed that the DDSs improved their accuracy across the board. The DDSs increased their initial claims decisional accuracy from 93.8 percent to 95.5 percent. They increased their reconsideration decisional accuracy from 91.9 percent to 95.3 percent. Moreover, they increased their CDR decisional accuracy from 95.6 percent to 97.7 percent.17

As required by the Act, we perform a pre-effectuation review of at least 50 percent of all DDS initial and reconsideration allowances for SSDI and SSI disability for adults. We also review a sufficient number of DDS CDR determinations that continue benefits. These pre-effectuation reviews, which are separate from the OQP reviews mentioned above, allow us to correct errors we find before we issue a final decision. These reviews result in an estimated $558 million in lifetime program savings, including savings accruing to Medicare and Medicaid. Based on our most recent data, the return on investment has been roughly $11 for every $1 of the total cost of the reviews. 18

To improve the consistency and quality of DDS decisions, we established the Request for Program Consultation (RPC) process. The RPC process allows DDSs and our quality reviewers to resolve differences of opinion they have on cases that OQP has cited as deficient. In general, DDSs use the process to resolve the most complex cases. Our policy experts in headquarters thoroughly review these cases. We post all RPC resolutions and related data on our intranet. The process serves several key functions. It provides real life examples of proper policy application, identifies issues and areas for improved disability policy, and provides our regional offices and DDSs information to assess local quality issues. Since 2007, we have reviewed almost 5,000 cases and posted their resolutions online. Further, the RPC team has worked directly with policy components to develop policy clarifications, training, and other resources that can further improve the consistency and quality of disability determinations at all adjudicative levels.

The Act and our regulations set out a process to help a DDS that does not meet our expectations. Currently, our threshold level for performance accuracy in the DDSs is 90.6 percent. When a DDS falls below that threshold during a quarter, we notify the DDS in writing and provide performance support. Based on available resources, we may work with the DDS to identify the root cause for the drop in quality and to prevent another quarter below the threshold. Corrective actions may include DDS in-line and end-of-line quality reviews and additional training. We then provide the DDS a threemonth adjustment period. We have provided optional support to States that have fallen below the accuracy threshold for two consecutive quarters. With our help, those States improved their accuracy rates to meet our threshold level. All DDSs are currently meeting performance accuracy expectations.

Budget Process

When we develop the DDS budget, we initially estimate how much funding DDSs require to do their three workloads: initial disability claims, reconsiderations, and CDRs. We consider actuarial forecasts for initial disability applications, Administration and congressional priorities (such as program integrity), staffing levels, attrition rates, and productivity. We determine our expected case production and desired workload targets, and we decide the amount of resources that DDSs need to meet those targets. We formulate an Annual Plan in advance of a fiscal year; we ask our regional offices and DDSs to submit their estimated funding and capacity needs based on a national estimate for workload processing.

As the appropriations process unfolds, we constantly communicate with our regional offices and DDSs and adjust the Annual Plan as necessary. Based on the resources that Congress appropriates, we adjust our case production and workload targets as necessary. Once we determine the pool of money available for DDS work, we allocate funding to individual DDSs according to our targets in the Annual Plan. During the second and third quarters of a fiscal year, we also conduct a quarterly spending plan process to allow the regional offices and DDSs to update their plans based on workload targets, any changes in the budget, and actual DDS spending and staffing changes.

Current Challenges and our Response

Prior to FY 2009, we received about 2.6 million initial disability claims each year. Since 2009, that level has increased dramatically; in FY 2011, we received nearly 3.3 million disability claims. We moved nimbly to shift resources into initial claims in order to help the States avert a potential new backlog. We hired approximately 2,600 DDS employees in FY 2009 and FY 2010; those hires became fully productive in FY 2011.

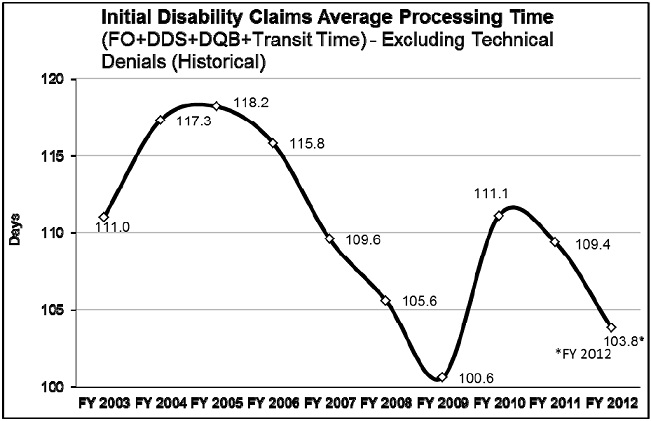

In addition, we developed flexible national resources to help us quickly direct additional support to the most stressed DDSs. We created Extended Service Teams (ESTs) in four DDSs with a history of high quality and productivity (Arkansas, Mississippi, Oklahoma and Virginia), and we increased the capacity of our Federal disability units across the country. As a result, we completed a record number of initial claims in FY 2011 and reduced our pending claims from our historic high in FY 2010. The dedication of our DDS staff and support from these national resources have helped us keep initial disability claims significantly below projected spending levels. Furthermore, as the chart below shows, our average processing time of 104 days to date this year is near a record low since we began tracking the current measure. Our success during a time of abruptly increasing applications is a tribute to the skill and dedication of the State employees who handle these claims.

Our FY 2012 funding is about $1 billion less than the President’s request. Based on this funding level, we expect a net loss of 3,000 State and Federal employees this fiscal year, which is on top of the 4,000 State and Federal employees we lost last fiscal year. With the hiring freeze in FY 2011 and only limited critical hiring in FY 2012, this level of performance will be short-lived. We project the amount of time it takes to decide a disability claim will increase to 111 days by the end of this fiscal year. Similar to our successful strategy for eliminating the hearings backlog, reducing the processing time for initial disability claims will require a multi-year approach.

The Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) outlined a level of program integrity funding that would have required DDSs, with the help of our national disability resources, to complete 569,000 CDRs in FY 2012-- a 65 percent increase over the FY 2011 CDR level in addition to a continued high level of initial disability claims. Unfortunately, our FY 2012 appropriations did not provide the BCA level of funding for program integrity work; therefore, we can only complete 435,000 medical CDRs this year.

In addition, we have evaluated our extremely limited resources, our success in holding down the initial disability claims pending level and average processing time, and a further spike in hearings requests. As a result, we decided to temporarily redirect our Federal disability units, which would have helped handle the BCA level of CDRs, to help screen hearing requests for cases where they can make fully favorable decisions without the need for a hearing before an ALJ.

Further exacerbating the our challenges in handling initial disability claims is the

decision of many governors to respond to fiscal crisis by furloughing DDS employees

whose salaries and benefits we fully fund. Since December of 2008 through February

2012, DDS furloughs have resulted in $53 million in delayed benefits and about $108

million in lost administrative funding to the States. More information on DDS furloughs

is available at www.ssa.gov/furloughs. We encourage you and your constituents to visit

the site, and we are happy to work with you on this issue.

Despite the many challenges we face in the DDSs, we are doing what we can to make our disability processes more efficient. We have developed faster and easier online services to meet the Baby Boomers' expectations and keep pace with the high number of disability claims.

Our easy-to-use online application, iClaim, has been a huge success. Disability applicants can now file for benefits online at their own pace and on their own schedule. Meanwhile, the increase in online claims has helped us to deal with the additional economy-driven claims and to reduce our field office waiting times. In FY 2009, we rolled out the first phase of iClaim, and we immediately saw a significant increase in internet claims as a result. Our numbers continue to increase. In FY 2011, more than one million SSDI claimants (33 percent of the total) filed online, almost quadrupling the volume from the year before iClaim. For the first 5 months of FY 2012, 37 percent of SSDI claimants filed online.

We are continually identifying ways to streamline the disability claims process. Over the next several years, we will be making significant improvements. We are modernizing our internet disability appeals by streamlining data collection and improving functionality. To make our electronic folder completely electronic, we will begin capturing electronic signatures for medical authorization and allowing users to upload supporting files directly into our disability systems.

As we expand and improve our online services, we must provide the DDSs with the tools they need to quickly and accurately decide disability cases. In addition to the CAL initiative I discussed earlier, our Quick Disability Determination (QDD) uses a computerbased predictive model in the earliest stages of the disability process to identify and fasttrack claims where a favorable disability determination is highly likely and medical evidence is readily available, such as low birth-weight babies, certain cancers, and endstage renal disease. We expect that our enhancements to QDD and CAL will allow us to fast-track about 165,000 claims for the most obviously disabled Americans while maintaining decisional accuracy. Identifying and paying clearly eligible claimants early in the disability process benefits persons with severe disabilities, and at the same time, it helps our backlog reduction efforts.

The Electronic Claims Analysis Tool (eCAT) is a web-based application designed to assist the examiner throughout the sequential evaluation process. eCAT helps examiners document, analyze, and adjudicate critical aspects of disability claims consistent with our policy. eCAT uses “intelligent” pathing whereby user-selected options determine the subsequent questions and guidance presented. eCAT’s features, such as quality checks and quick links to relevant references, aid examiners in producing well-reasoned determinations. This documentation is particularly useful for future case review because it enables an independent reviewer to understand the examiner’s actions and conclusions throughout the development and adjudication of the claim.

In addition to enhancing the documentation, quality, and consistency of our disability decisions, eCAT has been an extremely useful training tool for new examiners in the DDSs. Training through eCAT is helping new examiners more quickly gain proficiency in handling complicated cases. We are currently planning for every State to fully implement eCAT by September 30, 2012, which is a testament to our partnership with the DDSs.

We continue to make significant progress in developing the Disability Case Processing System (DCPS). DCPS will replace the 54 different COBOL-based systems that support the DDSs with state-of-the-art web-based technology. This system will integrate case analysis tools and health information technology (health IT). It will allow us to disseminate policy changes faster, and it will improve consistency among the DDSs. It will save money because each time we want or need to modify our system, it will be one set of changes instead of 54 very different sets of changes. We expect the changes to improve processing times and decisional accuracy. We plan to begin testing the initial version of DCPS later this year. We believe full DCPS implementation will make it easier to implement other important technology changes to improve the disability process.

Health IT is one of those important technology changes because it has the potential to revolutionize our disability determination process. We rely upon doctors, hospitals, and others in the healthcare field to timely provide the medical records that we need; we send more than 15 million requests for medical records annually. This largely paper-bound workload is a very time-consuming part of the disability decision process. As the medical community moves toward electronic health records, we are moving towards an electronic system of requesting and receiving medical records. With the consent of our claimants, we will have near instantaneous access to their medical records. Health IT will dramatically improve the speed, accuracy, and efficiency of this process, thus reducing the cost of making a disability decision for the both medical community and the taxpayer. Once health IT becomes standard, our accuracy should improve significantly and we, along with Congress, will want to study changes to the disability process that build on this success.

In addition to paradigm-shifting technology, streamlining and updating our business processes will also help us to decide claims more quickly without disadvantaging the claimant. For example, we allow adjudicators to proceed to step five of the sequential evaluation process when we have insufficient information about a claimant’s past relevant work history to make the findings required at step four. In certain cases, if we find that a claimant is able to do other work based solely on his or her age, education, and RFC, we could deny the claim without determining whether the claimant is able to perform past relevant work. This change would promote administrative efficiency and help us make more timely disability determinations.

To make consistent, better-informed decisions on whether disability claimants meet our disability criteria, we are developing a new Occupational Information System to replace the Dictionary of Occupational Titles. In FY 2009, we convened a panel of experts to guide us in the development of the Occupational Information System. In FY 2011, we developed a research and development plan that we will update annually, and we completed critical baseline activities to inform the design of the Occupational Information System. In FY 2012 through FY 2013, we will design and develop prototype components of the Occupational Information System, which will lay the groundwork for pilot testing scheduled to begin in FY 2014.

Reducing the Hearings Backlog

Congress has made it clear that addressing our hearings backlog is still our top priority. We have made great strides in cutting the average wait for a hearing decision from a high of nearly 18 months to below one year for the first time since 2003. We have drastically reduced the wait for justice despite receiving a 45 percent increase in hearing requests since FY 2008. In fact, we estimate that we received over one million more hearings requests than we expected when we implemented our 2007 hearings backlog reduction plan. We are so close to achieving our commitment to reduce the average wait for a hearing decision to 270 days by the end of FY 2013, but severe budget cuts for the last two years and associated the inability to hire a sufficient number of ALJs are challenging our progress. Nevertheless, we are doing everything we can to achieve this commitment. We are working with the experts and the Office of Personnel Management to address our needs to identify and hire qualified ALJs in the near-term as well as the long-term to help meet our commitment.

SSDI Demonstration Authority, Work Incentives Simplification Pilot

Our authority to initiate demonstration projects to test changes to the disability program rules expired in December 2005. The President’s FY 2013 budget includes a legislative proposal that would give us the authority to initiate new projects for five years, which is important for generating and testing new ideas for how to improve the SSDI program. One of the ways we would use this demonstration authority would be to initiate the Work Incentives Simplification Pilot (WISP).

The current set of work incentive policies and post-entitlement procedures have become very difficult for the public to understand and for us to administer effectively. The goal of WISP is to conduct a test of simplified SSDI work rules, subject to rigorous evaluation protocols, that may encourage beneficiaries to work and reduce our administrative costs. WISP would eliminate complex rules on the TWP and EPE. It would also eliminate performing SGA as a reason to terminate benefits. Further, we would count earnings when they are paid, rather than when earned, which would better align the rules of the SSDI and SSI programs. If a beneficiary’s earnings fell below a certain threshold, we could reinstate monthly benefit payments as long as the person is still disabled.

WISP has great potential to both encourage individuals with disabilities to return to work and simplify administration of the disability program. We urge you to support this legislative proposal.

Conclusion

Since 1956, Social Security disability benefits have provided a vital safety net for those Americans who constitute the most vulnerable segment of society. However, over time the program has become more difficult and complex to administer. We strive to provide the best possible service to these Americans, and we continuously look for ways to improve. Our IT investments and policy improvements demonstrate that we understand that we cannot do business as we always have.

We are proud of our efforts over recent years to improve how we manage our disability programs. Social Security remains a sound investment. Our administrative costs are very low, and our productivity has increased by about 4 percent each of the last 5 years. We have been able to absorb the increase in disability claims because the DDSs have done an exemplary job of keeping pace with it, but the gains we have made are not sustainable without adequate funding. We urge Congress to provide us the level of funding that the President has requested for us in FY 2013.

Tough choices loom. The complexity of the disability programs requires skilled employees to make disability decisions. Uncertain budgets make it hard to replace the experienced employees because we do not know if we can afford to keep new hires.

I am happy to work with you as you consider ways to improve the disability programs.

______________________________________________

1 See http://www.socialsecurity.gov/legislation/testimony_120211.html.

2 The Social Security Amendments of 1972 created the SSI disability program for children under age 18, using a definition of disability that was based on “comparable severity” to an impairment that would be disabling for an adult. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 amended the Act to create a separate definition of disability for children seeking SSI. To qualify for SSI disability benefits, a child must have a physical or mental condition that results in marked and severe functional limitations. This condition must have lasted, or be expected to last, at least one year or result in death. My testimony will focus only on the definition of disability for SSDI workers and SSI adults.

3 H.R. Rep. No. 1189, 84th Congress, 1st Sess., at 3.

4 The 1967 amendments also changed the definition of blindness from central visual acuity of 5/200 or less to the current standard of 20/200 or less.

5 Pub. L. No. 90-248, § 158, 81 Stat 821, 868.

6 This extension was in the Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA 1987).

7 Initially a temporary provision, Congress made it permanent in OBRA 1987.

8 For blind persons, the SGA earnings limit is currently $1,690 a month. Currently, other disabled persons are

engaging in SGA if they earn more than $1,010 a month. Both SGA amounts are indexed annually to average wage growth. However, the Act specifies that we cannot necessarily count all the person’s earnings. For example, we deduct impairment-related work expenses when we consider whether a person is engaging in SGA

9 This law also focused on other aspects of the evaluation process. For example, it temporarily codified our existing policy for evaluating pain and other symptoms.

10 Prior to this law, our regulations required a claimant to have at least one severe impairment. Thus, we would have denied claimants who had two or more non-severe impairments, but no severe ones.

11 We have also revised our listings to meet statutory requirements. The Social Security Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984 required us to revise the criteria under the Mental Disorders category.

12 Under those regulations, we will give controlling weight to a treating physician's opinion if it is well-supported by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques and is not inconsistent with the other substantial evidence in the record. In that case, a disability adjudicator must adopt a treating source's medical opinion regardless of any finding he or she would have made in the absence of the medical opinion.

13 H.R. Rep. No. 544, 90th Congress, 1st Sess., at 30.

14 A claimant can apply for disability benefits online, by telephone, or in a field office. A claims representative

interviews all claimants filing their claims by telephone or in a field office. During this interview, the claims

representative explains the definition of disability and our disability claims process and obtains all required

applications and forms. When claimants file online, our system provides the definition of disability and an

explanation of the claims process, and a field office employee reviews the information the claimant provides.

15 To help ensure disability adjudicators apply our policy uniformly at all levels, we use the same language in all of our policy instructions when communicating our policy to our adjudicators. We have followed this practice since 1996.

16 A different adjudication team that was not involved in the initial decision makes this reconsideration. We are

currently conducting a prototype project in ten states that authorizes the disability examiner to make the initial

disability determination alone (instead of working with a medical or psychological consultant) in some cases and eliminates the reconsideration step.

17 The percent is based upon a statistically valid sample of cases OQP reviews. It reflects the percent of cases

reviewed where OQP agrees with the decision made by the DDS.

18 Details can be found in Annual Report on Preeffectuation Reviews at

http://www.ssa.gov/legislation/PER fy09.pdf