Social Security Pioneers

Clark Bane Hutchinson

on her father

FRANK BANE

|

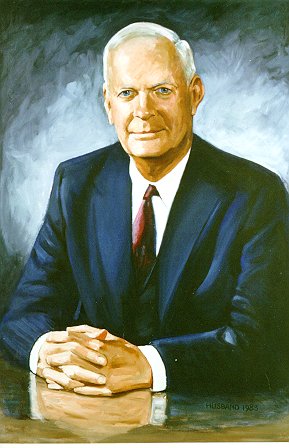

Frank Bane, from an oil portrait commissioned by Clark. There were four paintings made by artist John Husband, based on a photograph of Frank Bane. This particular portrait was painted in 1983. Donated to SSA History Archives by Clark Bane Hutchinson. |

|

Clark Bane Hutchinson, during her oral history interview, July 18, 1997. SSA History Archives. |

Soundclip excerpt from Mrs. Hutchinson's interview (in RealAudio format) |

Highlights of Frank Bane's Career |

Born: Smithfield, Virginia, ; son of Charles Lee and Carrie Howard (Buckner) Bane, April 7 1893; A.B., Randolph-Macon College,1914; Student at Columbia University, 1914-15; Cadet-Pilot, Aviation Corps, U.S. Army, World War I, 1917-1918; Married Lillian Greyson Hoofnagle, August 14, 1918, Children: Mary Clark, Frank; High School Principal, Nansemond County, Virginia, 1914; Superintendent of Schools, 1916-17; Secretary Virginia State Board of Charities and Corrections, 1920-23; Director of Public Welfare, Knoxville, Tennessee, 1923-26; Associate Professor of sociology, University of Virginia, 1926-28; Commissioner of Public Welfare, Virginia, 1926-32; Member of the President's Emergency Employment Commission, 1930-31; Director of the American Public Welfare Association, 1932-35 ; Lecturer in public welfare administration, University of Chicago, 1932-; General Consultant to the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, 1933; Consultant on Public Welfare Administration, Rational Institute of Public Administration, 1930; Consultant, Brookings Institute, 1931-35; Executive Director of Federal Social Security Board, 1935-1938; Director of the Division of State and Local Cooperation, Advisory Commission of the Council of National Defense, 1940-41; Member of Civilian Protection Board, Office of Civilian Defense,1941; Director of Field Operations, Office of Price Administration, 1941-42; Homes Utilization Division, National Housing Authority, 1942; Secretary-Treasurer, Governors' Conference, 1938-1958; Executive Director, Council of State Governments, 1938-1958; Chairman, Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations, 1959-1966; Regent's Professor, University of California, 1964; Lecturer, Seminar of American Studies, Salzburg, Austria, 1966; Lecturer, various universities, 1966-1976; Guest Speaker and Lecturer, various Washington-area universities, 1977-1982 Died: January 23, 1983, in Alexandria,Virginia at age 89. Buried in Arlington National Cemetery. |

Clark Bane Hutchinson This is an interview with Clark Bane Hutchinson. The interviewer was Larry DeWitt, SSA Historian. The interview took place on July 18, 1997 at Mrs. Hutchinson's home in Wilmington, Delaware. |

Before the formal taping began Mrs. Hutchinson was reviewing some of the documents she had regarding her father, including material she had previously sent to a researcher in Virginia.

Clark: All my brother sent him was the birth certificate and the death certificate and my daughter was calling me about it. She had a summer home near my brother's in Berkeley Springs, West Virginia.

So I sent all of his stuff to him and then sent his papers to the University of Virginia and that is in here. I have a double of that. I called to thank him and he said, "I've gotten so interested that I want to write a book."

I: You haven't heard from him and followed up with that?

Clark: No. His job is to write for the Historical Society of Virginia. I'm sure if he did he would let me know and part of it would go to the University of Virginia Library. Daddy used to lecture there.

Do you smoke? Does smoking bother you?

I: No. No go right ahead.

Clark: Oh great. I don't smoke in other peoples houses, but I like to smoke in my own!

Now I had all of these notes I made, because I thought that I would discuss various things with you. But before we start taping I wanted to look through some of this material.

(At this point Mrs. Hutchinson showed the interviewer some news clippings about a prank her father participated in during his college years at Randolph Macon Men's College. Bane was on the football team and he and his fellow team mates were suspended due to the prank and could not play. President William Howard Taft intervened to get the suspensions lifted. One of the young men who approached President Taft was H. Barett Prettyman, who would go on to serve as Soliciter General during the Taft's tenure on the Supreme Court. The two had a good laugh years later over this episode.)

Randolph Macon had two hundred students (during this time). I met somebody in Florida who, believe it or not, he and I were born in the same hospital, I met him six months ago, and his father was in the same fraternity with my father--two hundred people at Randolph Macon Men's College and he was in on this.

Now this is just for you to read for fun, it will only take you a second. They don't tell you what they did to get in trouble, but what they did was they had a little too much to drink and they put a cow up in the steeple at church!

I was just thrilled to death with this.

I: Yeah. Yeah. This is really nice. This is great that you got a copy of this.

Clark: You must read fast.

I: Well I'm not going to read every detail of it now.

Clark: Well you should, because it is the funniest story that I've ever heard.

I: That is a nice line. "You boys have your little fingers caught in the crack of the log and you want the President to put his big fingers in the crack so that you can get your little ones out." (Referring to President Taft.)

Clark: Yes, and he weighed 375 pounds!

I: (Reading another quote from the article.) "If they were locked up in the Federal Penitentiary over which he had authority he could release them."

Clark: You know that he never wanted to be President, it was his wife that wanted him to be President.

I: The President pleaded their case so that they could get released by the faculty to play.

Clark: And they weren't going to get any money from the alumni either.

I: Yeah I bet that is true. This is a cute story.

Clark: And then I just have this. . . This will give you an idea of what kind of a young man he was. He had the best sense of humor that you have ever seen in your life. And you know when you think of somebody you don't think of their personality.

I: Right. No, no. That is important, I am very interested in things like that, because it really helps to make the history vivid to people. If you can give a little of that color and a little bit of the personality then all the facts and figures have some life to them. Football, Baseball, and Latin. (Shown as Frank Bane's interests at school.)

Clark: He flunked Latin five times.

I: Is that why they put that in?

Clark: Yes, and I flunked it twice. So I had to take a Bachelor of Science degree because I couldn't pass Latin. And when the University of Chicago Dean said, "You can pass it." I said "No I can't. I am just like my daddy and he flunked it five times in college . . ."

I: And look at him he was a success! Now before I forget let me show you something that I brought you. About what I did with the portrait and how we are using it. Now I didn't take a photograph of it yet, because this roll of film isn't ready to be developed so I didn't have a chance to take a photograph. But I took a photograph with my little digital camera, which doesn't use film, it just plugs into the computer and then you can see it on the computer screen and print it out in the printer. So I just printed out a copy to show you and later I'll take a photograph.

Clark: Then we will all come to see it.

I: Yes, certainly. This is the entrance to our History Room. There is a big room here with all kinds of displays, but it is right in the front entrance in display with the portrait. And then there are a couple of other things there, a couple of pictures of your father. These are 8 x 10 pictures I had of him and a picture of him with members of the Social Security Board. And a copy of an article that he wrote for our employee magazine in 1977.

Clark: Yes. You call that OASIS. I gave you a copy of that, because I didn't know if had copies.

I: And this is of course a little description, a little bio, a little description of your father and his role in the organization. So that is right in the door as you walk in the door it is right by the plague.

Photo gallery of Frank Bane as Director of Council of State Governments

Clark: And I have something here that I am giving you. Have you ever heard of Louis Brownlow?"

I: Yes, sure.

Clark: Well he was like my grandfather and I have something here just for you to read. This is the first time that he ever met my father. . .

"Frank Bane has a knack of getting group consent to a specific program because he is a genius at simplification. Time and time again I have seen him go into a meeting where the most diverse views were held by the most belligerent persons, each declaring that he would never yield a jot or a tittle, and yet Bane would come out at the end of a long discussion with a unanimous agreement. Invariably that unanimous decision will have the form of three, four, or five propositions. Always they are numbered 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Never are there more than five. Rarely does one of them exceed a sentence in length. Rarely does the whole document cover more than a page. The reason Bane gets them together is that he is able to distill out of intellectual discussion and the emotional quarrels basic propositions on which the group can be brought to agree, and he has the knack of writing them out in simple, direct and brief form. His success is largely due to the fact that he is able to add to his genial personality this particular piece of technical skill."

|

I: This is from Brownlow's book?

Clark: Yes. And Brownie took daddy. . . Daddy said that he learned everything from social workers, and women social workers. And some of the smartest people he ever met were women. And daddy and Brownie would go to meetings . . .

Daddy loved to dance and my mother had two left feet. And so he had bet somebody ten dollars that I could dance before I could walk, and he won. He took me when he was a Principal of a school he'd take me to the school band and put my play pen right next to it and he won his ten dollars. And I did the same things with my two grandchildren.

I: They would dance to the music?

Clark: I had them dance before they could walk.

But this the first time Brownie ever met daddy. I read his book and stayed up to 5 o'clock reading this. It starts right here . . . My dad at this time is like 28 years old.

I: What was he doing at this time? What was your dad doing?

Clark: There was no Social Security then. His job was to work with the jails and the insane asylums and the reformatories.

I: In the state of Virginia?

Clark: Yes, and the poorhouses. Brownie, if you didn't know, he was very pompous.

I: So tell me about him. I would be happy to hear you tell me about many of these people that you met--these famous people that we've all heard about. I would be delighted to have you talk about them.

Clark: Well he was like my grandfather from the time I was two years old.

They would go to all of these meetings together and then they would go to dances and Brownie couldn't dance. So one time Brownie was telling daddy not to tell anybody, and he was 58 years old, but he said, "I am sick and tired of sitting at the table when you dance. So I went to Arthur Murray and took dancing lessons."

And so mother and daddy gave Brownie a coming out party at the Quadrangle Club at the University of Chicago. I get a phone call at 9:30, "Toot's get dressed in an evening dress and come right over. None of the women know how to dance the new dances that Arthur Murray taught Brownie."

So up unto he was 80, Brownie and I went dancing together all of the time.

They used to have tea dances at the Press Club every Saturday. And if I was ever in Washington working or anything we went every Saturday to tea dancing. And the last time we went dancing he was 79, and he died at 80 making a speech on a platform.

I: I didn't realize that. How interesting.

Clark: Fourteen of my family were here for a child that got married. I have one married for 20 years. I have five children, and none of the others were married and then I had three get married in 3 years.

I: Oh? How nice.

Clark: I have one left who isn't married, and he is in Kuala Lumpur. I thought that . . .

I: You can proceed however you want.

Clark: So this recorder is turned on? So you have got all of my crazy conversation?

I: Yes that is fine, don't worry about it.

Clark: I thought this would explain something about daddy. Karl Menninger was on a lot of daddy's boards throughout the years. One time he said to daddy, "Tell me about your childhood. You are the best adjusted person I've ever met in my life. How come?" And dad said, "Well my mother died when I was three and I was raised by a colored mammy." And I said that my dad is the only person that I ever knew with no prejudices against any group or any person.

Mary Bethune used to come and stay at our house and when different colored people would come and make speeches they would always come and stay at our house when they couldn't stay at hotels. And we had the same maid for 26 years and she was just as close to me really as my mother was.

Bill Robinson, the tap dancer, was from Richmond Virginia. And he built a settlement house for children in Richmond. Daddy always arranged to go to the settlement house one Saturday a month to see the woman that ran it. (This was part of his job for the State of Virginia.) And he would take me when he went to the settlement house. That is where I learned to do the Charleston and the Black Bottom. And I played as much with colored children as I did with white children. There were white children in my neighborhood.

But as a result I ended up with no prejudice. As a result all of my kids have friends that are colored. And I like that word much better than "black" and "African-American," and as long as there is the National Association of Colored People, I'm going to call them colored.

And all of my children were saying, "How come you are more comfortable with our colored friends than we are?" And I said. "Because I've known them all of my life and I have never felt any different with them."

I: Tell me, just give me a outline, where you lived over the years. Because it sounds like the family lived different places over the years.

Clark: Yes, you will find the whole history of where we lived in that oral history, which is a great history. (Referring to a previous oral history her father gave to the University of California in 1965.)

I: Yes. I'm anxious to get my hands on that. It turns out that I can't get it for two to three months. For some reason it is going to take them three months to send it to me.

Clark: Well I bet that they are going to have to re-tape it.

I: Yes, well I think that they have to redo the transcript or something, I am not sure what.

Clark: I wasn't going to send you this one, it is the only one that we have.

I: Well I understand.

Clark: Well he started out . . . Do you want to know where he was born?"

I: Yes, tell me. Just give me the outline of where he was and then we will go back and talk about each of those periods.

Clark: His father was a minister, a Methodist minister, and he was born in Smithfield, Virginia. And Tom Dewey would always introduce him, in every speech that daddy made when Dewey introduced him, he would introduce him as "Frank Bane from Smithfield, Virginia--where the hams come from."

I: Ha, ha, ha! That's good.

Clark: And then his mother died when he was three. Then he had a brother and a sister and they moved in with his grandmother in Ashland, Virginia. They had lived in Charlotte, Virginia and the colored nanny is the one that raised daddy.

His brother later went to Randolph Macon and he became a lawyer and he worked for the Federal Trade Commission. Then he was head of the Legal Section of the Securities and Exchange Commission. When President Roosevelt appointed Kennedy, Joseph Kennedy, as Securities and Exchange Commissioner, my uncle asked him why and Roosevelt replied, "It is just to put the fox in the hen house."

I: Oh that is good. That is funny!

Clark: And then he went to a prep school. There are two Episcopal high schools in Virginia--one is in Lynchburg. And he played semi-pro baseball for Lynchburg--did you know that there is a Lynchburg league?

I: I didn't know that.

Clark: Yes. In fact there is--oh what was that movie? Bull Durham. It was in the same league. And he did that all the way through college.

Then he went to Columbia. Daddy told me that he had taken Political Science at Columbia and he had told my daughter that he had taken Law, and that in the summer he had worked at Sing Sing (the state prison). So when this man who was doing the biography of him went to look at his papers he found that daddy had taken Law and didn't like it and had switched over to Political Science.

Then the war came and he was in the Air Corps for two years, I think. He was in the Air Corps from 1916 to 1918, I think, and then he married my mother.

When the war was over he went to Nansemond County, Virginia, that is where Suffolk is and not too far from Norfolk, as Principal of a school. And all of this will be in the oral history. At 23 they made him Superintendent of the school. I was a year and a half old so I guess he was there for maybe a year-and-a-half or two years. And then he went to Richmond and that is where he met Brownlow. Because we moved to Richmond when I was 18 months old and stayed until I was three.

Brownlow was made City Manager of Knoxville, Tennessee and asked daddy to come to set up a Welfare Department there. And the fascinating thing was that daddy got there and found out the doctors were splitting fees.

I: What does that mean?

Clark: Well I send you a patient and then you give me half of what you charge that patient. So daddy took that to the courts and that isn't written up any place that I have read so far. But anyway he did away with it and he reorganized the whole medical profession. And so they said that if he got sick or if anything happened to us we were in "real trouble," because nobody, no doctor, would wait on us. Then mother had my brother when I was there and the doctor did do it, but the doctor said he should name my brother after him,(the doctor), since he was so nice to be the doctor after the trouble with daddy.

But then I'll get back to what I was doing about commenting . . .

I: Now I am going to take some pictures of you while we are talking . . . just keep talking don't let it distract you.

Clark: I never wear glasses except when I read, because I have cataracts.

Let's see, I remember when we were living in Richmond from the time I was six years old until I was eleven. That is the longest that we have ever lived anywhere when daddy was Director of Public Welfare.

Oh, he left Knoxville and then came back to Richmond when Bird became Governor and Bird wanted to set up a Welfare Department and I think it was the second Welfare Department that they set up in the United States. New York had the first one and Richmond had the second one. I don't know where Brownie went, when daddy went back to Richmond.

They used to take me to Sunday School. And my dad having had a father who was a minister, having gotten so many demerits when he was in college, and every time you got a demerit you had to memorize a chapter of the bible, so daddy knew any part of the Bible backwards and forwards.

I told daddy that I didn't like Sunday School. All that I heard about was the devil and damnation and I thought that religion should be happy. So daddy said that you don't have to go anymore.

So daddy started taking me to the colored churches, whenever we would be driving around the church would be in session, and we would sit in the back of the colored church. And so I don't know many hymns, but I know all of the spirituals from all of the colored churches. I can sing any of them.

He knew so many brilliant women and as I said they are the ones that really trained him in social work and made him the welfare worker and he brought some of the best ones in the United States to come and work with him in Richmond.

When I was seven he gave me a book on the Famous Women of The World and he said, "There isn't anything professionally that a woman can't do that a man can do, as long as she has the brains and the motivation." And I don't know if you've ever heard of Edith Abbot and Grace Abbot or Sophonisba Breckinridge?

I: Yes.

Clark: Edith Abbot was head of University of Chicago Social Work School, but Sophonisba Breckinridge started it. And they were from Kentucky and her father is the one who ran for President and was a Senator or Congressman during the Civil War time. She was one of my favorite people. I never came home to Chicago that she didn't have a present waiting for me.

Anyway we had that book for years and we moved so much that when I was away working I lost the book--I mean we had thousands of books, and I lost that book. But the thing was that I didn't have the motivation or the intellect . . . Well, I ended up with a Masters Degree in Social Work, but I majored in "social life" during high school. And now there isn't a single subject you bring up that I can't tell you about, because I'm hooked on Public Radio and I listen to it 24 hours a day.

I: That's good.

Clark: So now I'm bright, but at school I wasn't, but I had a glorious time.

I: Now your father, I think, had the view that a life outside of work was also important. Right?"

Clark: Oh yeah. But you know in those days you worked 48 hours a week and then he always worked overtime.

Did I send you the article of me that I was talking about meeting with Mrs. Roosevelt for the first time?

I: Was that in that newspaper clipping?

Clark: I went to my son's 40th birthday party and met this young man who was fascinated about government. And I was talking to him, about it. So the man came and interviewed me about knowing Mrs. Roosevelt and I ...

I: Well tell me that story again and we will put it down on the tape.

Clark: Well let me, well what I will do is I'll give you a copy of that. I am pretty sure that I gave you a copy.

I: Let me look maybe I have it.

Clark: You know you can just put this in here and just read this later. Now what was the question that you asked me?

I: You were going to tell me a couple of things, you were going to tell me . . . why don't you tell me the story of meeting Mrs. Roosevelt?

Clark: Starting when I was two years old daddy took me on all of his business trips all around Virginia. So I went to all of the insane asylums and all of the reformatories. And the people in the prison made me a doll bed. And I would go up to every body in the jail or reformatory that I met and I would go up to all of them and say, "What did you do?" And then I would say, "You promise that you will never do it again?" And that went on until I was five years old and then I stated kindergarten.

But he would take me all over Virginia to all of these different institutions. He had a very beautiful voice and he taught me all of the World War I songs and all of the songs from 1910 to 1930 and then from 1930 I taught him all of the songs. But on these trips he would sing to me and he would quote poetry.

I: So he took you around . . .

Clark: From the time I was two. And at the University of Virginia he would sit me down on a bench and then he would go and lecture and then he would come back and pick me up on the bench. And he would show me where the lavatory was, and where to wait for him.

When they moved from Suffolk ,Virginia . . . they grew up in a little town called Ashland, Virginia. It still is a little town. The population is now two thousand four hundred and when they grew up there the population was like two thousand five hundred. It is the only place that hasn't changed. The house where my mother lived is still known as the Hoofnagle house. The houses are still known. The Prettyman's house is still known as the Prettyman's house. The man that owned the race horse "Citation" lived four houses down from where my grandparents lived, and right behind their house was a minister named Hepburn, and that was Katherine Hepburn's grandfather.

I: No kidding? Isn't that amazing?

Clark: So one time (Katherine Hepburn) came and did Jane Eyre in Washington when I was around sixteen or seventeen. I saved all of my money to go to see the play and when she came out I was standing outside and she said, "Did you like the play?" And I said, "I loved it!" And I said, "Do you know that my grandfather lives right behind your grandfather?" And she said, "Isn't that fascinating? Why don't hop in the car and we'll talk about it?" Imagine this gracious lady doing this to this seventeen year old kid.

I: Wow! What a great time. What a great story!

Clark: That little town is still exactly like it used to be.

Instead of reading poems like A. Milne and all my father would read me Kipling and Robert W. Service--starting when I was four, five, and six years old. And when I was in the second grade . . . did you ever read Robert W. Service or Kipling?

I: I read some Kipling.

Clark: Well he wrote some things about India and then he wrote some very naughty ones.

I: Oh I see, the ones that I read were about India.

Clark: In the second grade I had to memorize a poem and do it. And so daddy taught me Kipling's "If You Had Your Choice Of Two Women To Wed." And it goes, "one is beautiful and kind of sinful and the other is ugly and a puritan," and it ends asking "would you take a scarlet saint or a sparkling sinner?" And when daddy came home from work that night he came rushing in and said, "How did you do your poem and what did you say?" And I said, "The teacher said that I said it well, but it was not appropriate"

I: That's funny! I am very interested in the fact that your father took you around as a young girl and let you watch his work and see where he went and what he did.

Clark: Well he had to drive all over the state and he thought it was more fun to (take his little girl along). When mother was pregnant he said, "Nobody will believe it, but I hope it's a girl, because a girl you can spoil."

We did all of the singing together, but I did not inherit his singing voice, I can't carry a tune and I have to mouth things.

He would come home from work every day and I would meet him at the door and I would reach in his pockets and he had Hershey Kisses and so I would call them "Pocket Kisses" instead of Hershey Kisses.

We had a big broom for my daddy and a little broom for me, and then we would walk around the dining room table before dinner and be soldiers and sing all of the war songs from World War I.

My brother was born seven years later. When he was born that is when daddy was Director of Public Welfare, and then he was very young. After that we moved to Chicago and as head of the American Public Welfare Association he was only home a week out of a month. So he never got to know my brother as well as he got to know me. And so I was lucky as a "duce" to be around (in the early days).

I: Now you mentioned a minute ago that your father said, that a lot the women in the social work field were an influence on him and a lot of women were important in his career. Can you think of anybody specifically that he had in mind? Anybody that you want to mention now or are you going to mention them later?"

Clark: Well Edith Abbot and Grace Abbot and Sophonisba Breckinridge and there was somebody named Hoey.

I: Oh yeah she worked at Social Security.

Clark: I've got some material . . .

I: Oh good, oh good. I am very interested in her.

Clark: Where he is giving her a farewell party and then he wrote her a letter about the "red-headed gal" that he talked into coming down from New York, because she really didn't want to come down to Virginia, I mean to the Social Security, to Washington.

I: Okay yeah, Jane Hoey.

Clark: Jane Hoey was there a lot longer than daddy was.

I: Right she stayed a lot longer after he left.

Clark: And then I don't know if you have ever heard of Maurine Mulliner?

I: Oh sure, and as a matter of fact . . .

Clark: Did you see her in US News and World Reports?

I: No, but she was on ABC TV just two weeks ago. They interviewed her about . . .

Clark: It was some exercise thing that she did?

I: Recently? In U.S. News?"

Clark: Yeah it was two weeks ago. I have got that in here for you.

I: I think they interviewed her on ABC News too. I have been thinking of going to talk to Maurine about her oral history.

Clark: It is going to be hard trying to find her. She is not listed in the phone book.

I: I know where she is, I have her address.

Clark: Oh you do?

I: I have her address and phone number. I didn't bring it with me. I have it in the office. I will call you and give it to you.

Clark: Oh my heavens! I will call and get it. When my daughter was here from Puerto Rico she went down there to try and find Maurine and she is not listed in the book.

I: Yeah I've got it. I'll give it to you.

Clark: But they said in here that she is still active in the Unitarian Church.

I: Oh how interesting!

Clark: So I said to call the minister there.

I: In fact, I have an oral history interview by her in which she mentions your father a lot and I was going to ask you about some of the things that she said about him. She says some very flattering things about him.

Clark: One time after my daddy was a widower . . . Maurine did not like children and I have never seen Maurine really laugh. And I have known her . . . she came, she was Executive Secretary of Social Security Board.

I: Right.

Clark: And was hired by Winant. You know who Winant was? When they fired Joe Kennedy, Winant went over to England and she went with him.

I: That's right.

Clark: And another time when she went to England--I put this out, because I thought that you would be interested--she brought this back to daddy. That is after Truman fired General MacArthur.

I: Oh yeah. These are bottle stoppers (shaped to look like MacArthur and Truman).

Clark: But Maurine did not like children and she had a very peculiar growing up. She grew up in Utah and her parents were Mormons. Is this in her biography?

I: She didn't talk about that in her oral history.

Clark: She didn't get along with her parents and then her brother disappeared and she never found her brother. She kept in touch with her sister, but she went with Winant.

You will find here that daddy worked for Winant, to help setup, reorganize his government, when I was twelve years old, and that is where he got to known him.

I: To help Winant when Winant was Governor?

Clark: Yes, of New Hampshire.

I: Okay. So that is how he got to know Winant? And you met Winant then too?

Clark: Yes. And that is why daddy left Social Security. This is one of the things that I want back--daddy's description of Winant. And I have given you some things that are kind of private, but you can use them, I thought, with everybody dead now.

I: Sure. Okay, good.

Clark: Because Winant's wife . . . when we were in New Hampshire we never met her, she raised dogs and that was all that she was interested in. And she didn't go to Washington with him and she didn't go to England with him and then when he came back from England he committed suicide.

I: Right.

Clark: Daddy had a secretary, who he had for years, as Head of Council of State Governments, and she died and Maurine took off six months from work to go out and be daddy's Office Manager and get things straightened out that Mary Lou had done. And get the things all organized.

"Mr. Bane is the kind of man that is not only a lot of fun, but a rate privilege to work for. He is always gentlemanly, pleasant, and cheerful. He has a sparkling wit, and is one of the country's best story-tellers, I think, yet he give sober attention to the job at hand. He is generous with his time--and I should know--to the little fellow as well as the big one. You'll notice how his office door here is never closed. He keeps his staff well informed of all phases of our work, he details jobs to others, then lets them go ahead without interference and with a feeling that he has confidence in them." |

I: That's when he was at the Council of State Governments?

Clark: Yes. She just took a six-month leave of absence and then went back to Health, Education and Welfare. They were just the very best of friends. But life to her . . . it was so funny, because daddy was one of the few people who could really make her laugh. "Life was real and life was earnest" always with Maurine.

And when she had gone to take up ballet lessons at, she went to ballet school and was in the Chicago Ballet and then did something to her back, and so then went to the University of Chicago and got a Ph.D. I think, if I am not mistaken, in psychology. And she wrote a book, when she was a student, with the man who taught psychology there, a man named Mandell Sherman. And his graciousness is unbelievable. On the book he puts his name and her name just as big, as authors. Now you know most people will just list you in the credits or not even mention it.

I don't know how she got into Social Security. I did not know her during the Welfare years.

I: Actually I know that story. She worked for Senator Wagner from New York, and Senator Wagner recommend her to Winant, and that is how she got there.

Clark: Oh? She got there through Senator Wagner?

I: Yes. She got there through working for Wagner. Well why don't you just tell me about Winant too?

Clark: I know nothing about him, but there is a write-up in here, that daddy describes Winant. And he was the most peculiar person. Daddy was a day person and went to bed every night at nine. Winant could never make up his mind. As daddy was saying, Winant was the most unique and kind of peculiar person he had ever met. They would have a meeting and they would decide what they would do and then daddy would get a phone call from Winant at 2 o'clock in the morning saying, "Frank I am not sure that this is what we are supposed to do." And after three years of this, daddy went with the Council of State Governments.

Daddy said anyway that he loved taking different a job every three years, because that broadened his interest in things. Because if you stay too long you get stale. And you really don't add anything to the organization.

Frank Bane," declared Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen, "is the best administrator in the country." |

I: Tell me how about Winant, could you give me any description of him?

Clark: I never saw him.

I: Okay. So you never met Winant?

Clark: I never met Winant. We stayed out on Lake Winnipesaukee and daddy would go in to the Capital (to help Governor Winant) but Winant never had us for dinner.

Two years before he had done the same thing (consulting on government organization) for Tudor Gardener, who was Governor of Maine. And they had us for dinner and then they also took us down Kennebunkport River in a Criss-Craft. I had never been in a Criss-Craft before! And Tudor Gardener had a big place at KennebunkPort and he had us there for the weekend. And it was his son that later married a champion skater, who became a doctor and later they were divorced. But he was utterly charming.

I never saw Winant at all. I don't know if my mother ever saw Winant. We never had him over and we always had people over for dinner. But I don't remember Winant ever wanting to come.

Daddy was on the First Hoover Commission. That was the next thing. Back when daddy was in Virginia Hoover put him on this board to find out why they had the Depression. And I have the different articles that they wrote about where daddy told Hoover that there was no way that the private agencies could do it. You had to have public agencies coming in.

But daddy said that he made the biggest mistake that he ever made. He never made it again. A New York Times man came to interview him after one of the meetings and he said that Hoover was dead wrong, that there was no way that they could have private agencies do the things, and they had to have a welfare set-up. Hoover called him in on that. And daddy said that after that he was never "Frank," he was always "Mr. Bane."

And about 30 years later, or something like that, he gets a phone call from Hoover to come to New York and met him at the Waldorf Astoria. And then he said that he was setting up the Second Hoover Commission and he wanted daddy to help him set it up. So he had forgotten about the past.

I: So he worked on the Second Hoover Commission too?

Clark: No. No. He didn't go and work for them. But he was very flattered that Hoover asked him too.

I: Okay.

Clark: So the next thing was Frances Perkins. . . and you will see this in daddy's write up. Roosevelt was very much against welfare--he was running as a conservative Democrat. And if we wasn't against welfare he would not get any votes. So nobody could talk him into welfare.

But Mrs. Roosevelt, was very much interested in it. And Frances Perkins was one of her best friends and she was interested in it. And when she became Secretary of Labor, she suggested, and that is to Brownlow . . .

Oh, when daddy was on the Hoover board about the Depression, a man named Woods from The Rockefeller-Spelman Foundation was on it. And he became very impressed with daddy. So he went back and talked to the Rockefeller-Spelman Foundation about it and that is when they set up the American Public Welfare Association.

I: Okay.

Clark: And that was financed by the Rockefeller-Spelman Foundation.

And then Woods retired and a man named Guy Moffett took his place. Then daddy and Miss Perkins and Guy Moffett and Louie Brownlow and . . . oh let me think, Beardsly Ruml, who was a Professor, always wanted to be a Professor, but his father unfortunately owned Macy's Department Store, so when his father died he had to go back and take Macy's over. But I knew him when he was a Professor at the University of Chicago and I was a little girl. And a lot of them went to Europe, they went three times to study the European system. There was a German, years ago, not von Hindenberg, but one way back, that started the first Social Security setup in any government.

I: Right, that was Bismarck.

Clark: Bismarck! Thank you very much. So daddy was having lunch at the Dodd's house. Ambassador Dodd had taught my mother German when she went to Randolph Macon Women's College. When we moved to Chicago with the American Public Welfare Association he was Head of the German Department at the University of Chicago, and then Roosevelt appointed him as Ambassador to Germany.

Mother and dad were over in Germany doing this study and the Dodds had them over for lunch. And that is the day that von Hindenberg died and Hitler marched in. And so Mrs. Dodd after lunch was over said to mother, "Did you notice that the maid who served our lunch, changed in the middle of the luncheon?" Hitler had taken the kitchen help out and had put his people in without the Dodds knowing it.

I: Wow!

Clark: He started writing Roosevelt, and anybody in Washington that he knew, and the professors in Chicago and everybody and telling them what Hitler was doing to the Jewish people and nobody believed it. And I had dated his son when I was in high school--you dated everybody in those days. Anyway, Hitler said that he had to be fired, so Roosevelt fired Dodd and brought him back, but he still thought that Dodd was crazy. Nobody could be doing that to the Jewish people and he never believed it. My dad didn't believe it. And I said to daddy, "Why don't you?" Because the Dodd's were telling me this and I went over to their house several times. And daddy said, "I just think that he has had a nervous breakdown."

And so Dodd would go and speak anywhere he could on what was going on with the Jewish people in Germany. He could never get a big hall, so he would go to any little church or any little community group and I would go with his son and we would pass out pamphlets about it. And then Dodd had kind of a nervous breakdown and he was walking down a lonely road one night and was hit by a car and was killed in Virginia.

I: Wow.

Clark: But Roosevelt really didn't believe it. Honestly at that time the United States had no knowledge at all of it

I: Right, hardly anybody did.

Clark: And we didn't know about it until we found one of those concentration camps. But Dodd knew about it. He had a daughter named Martha Dodd, who became a very famous communist. That was during the McCarthy era, and so McCarthy was going to investigate her and have her arrested so she ran away to Russia and lived in Russia. I think that she was indicted for becoming a communist, and she wasn't a spy or anything. But she had such a reaction to the fact that the people wouldn't believe her father. And when Carter became President he pardoned her and said for her to come back to the United States and she didn't, but she went to Czechoslovakia and she had married a Russian.

"Bane, one of the wartime government's elite volunteer dollar-a-year men, had a reputation for handling gigantic tasks. He helped work out the nation's civilian defense plan and in three weeks was able to organize and start a rationing system."

|

I: How interesting! Wow! It is amazing how many different events that we have gone through here.

Clark: Oh it's unbelievable! Like when Guy Moffett took over the Rockefeller-Spelman Foundation, and at that time daddy was working for Social Security . . . Nothing is going to be in context . . .

Anyway, I was terrible in geometry and I didn't know that Guy Moffett was coming for dinner and I went down and said to daddy, "Can you help me with my geometry?" and daddy said, "No we are having company for dinner." And Guy Moffett had come and he was sitting on the back porch and he heard me and after dinner somebody knocked on my door, came up stairs and knocked on my bedroom door, and it was Guy Moffett and he said, "I'm awfully good in geometry may I help you with it?" And we became best friends from then on. Up until he died I would go and visit him where he lived in Virginia, after he retired. We wrote each other letters back and forth, we talked on the telephone, he never came to Washington that we didn't see each other and up until . . . In fact, have you heard of Luther Gulick?

I: No.

Clark: Well he was head of Political Science at Columbia. You will read about Luther Gulick, he was also setting up Social Security and he is in all of this.

I: Oh?

Clark: You said that you got some information from Columbia?

I: Well the Oral History interview. Your father had an oral history interview with Columbia, as well as the one out at Berkeley.

Clark: So Luther Gulick will be in that.

Well when Guy Moffett died, his wife married Luther Gulick. And I went to see them seven years ago and she was 96 and Luther was 99. Last time that I heard Luther was 101, but I haven't heard from him in seven years so I don't know if he is still alive.

I: How interesting. So now your father knew Frances Perkins because of his work with the American Public Welfare Association, or he knew Frances Perkins before that?

Clark: He knew her before that, and I don't know how.

But he knew Mrs. Roosevelt. Mrs. Roosevelt came to campaign for Al Smith in Richmond, because Roosevelt could not campaign. So we had her for dinner. And then daddy drove her throughout the state to do the campaigning, and I could sit in the back seat, if I didn't say anything. This is why I talk so much now, I was raised so that I could be seen and not heard. Because everything was political, so daddy never wanted me to discuss any of the things I heard. I was eight years old and for about four days I drove around Virginia with the two of them.

And they had a program on public radio, it wasn't Terry Gross, but somebody else in the area of Philadelphia, and she had Doris Kerns Goodwin on. And they were comparing Mrs. Roosevelt with Mrs. Clinton. Well I went apoplectic and I told them. . .

I: You phoned in?

Clark: Yes. And there were other people on the line, and they said, "What are you calling about?" And I said, "I've known Mrs. Roosevelt since I was eight years old and this comparison is the worst that I have ever seen." I never knew anyone, anybody, that was more gracious and more charming and more unassuming than Mrs. Roosevelt. And I never knew anybody that was more "bossy" and ungracious than Mrs. Clinton. So Doris Kerns Goodwin said, "You mean that you knew her?" "You knew her personally?" And I want to get in touch with her sometime to give her some more information about the Roosevelt family.

When Anna Roosevelt and her mother broke up at the time that Roosevelt died, because Anna Roosevelt had been arranging for, you know she found out about Lucy Mercer.

I: Right.

Clark: And so for three or four years they had nothing to do with one another. And there was a man named Paul Appleby, who was Henry Wallace's Assistant, when he was head of Agriculture. And then he was Assistant Head of the Bureau of Budget and then he headed the Maxwell School at Syracuse. And I had known his daughter years ago and then I went and had lunch and dinner with Maurine one night and she said that she was having dinner with somebody else and it was Ruth Appleby. Ruth Appleby was amazed that I had known her daughter 30 years ago and she and I became best friends until she died in 1996.

And she was the most brilliant lady. Ruth Appleby became Anna Roosevelt's kind of "surrogate mother" for those four years. And she kept in touch with them. Then she got to know Anna's daughter real well and then Anna's granddaughter real well. And she was also a good friend of Paul Douglas. So I was over to Paul Douglas' for several times and Anna's daughter was there.

And the only person that I have met that I have hated, every time he has walked into the room I got up and left, daddy let me get away with it, because he had been so rude so many times, was Harry Hopkins.

I: Oh really? Well tell me about him.

Clark: I just wanted to do the most interesting things. That is a person that I just knew very, very well.

I: You knew Hopkins very well?

Clark: Hated him! He went on every vacation with us in the summer.

To get back to Anna Roosevelt. Her second husband was a newspaper editor named John Boettiger. And he had twin daughters who went to the University of Wisconsin when I went there. I knew them, I used to play bridge with one every week, and they were absolutely devastated when their father divorced their mother and married Anna. And then later he was a newspaper editor in Seattle, Washington and he jumped out of the window and committed suicide.

But anyway she kept in touch. Ruth told me the story.

Harry Hopkins was married the first time and his wife worked his way through Social Work School.

I: She supported him while he went to school?

Clark: Right. And then he divorced her and left her with two kids. And married this beautiful, wonderful gal named Barbara. And they had a child named Diane and she died, Barbara died of a brain tumor.

Anna Roosevelt's third husband was a doctor, and he was like 60 or 70, and he wanted to write a book on Harry Hopkins' illnesses from a medical point of view. And so Ruth Appleby introduced him to Harry Hopkins' daughter who was like 30 years younger than he was, and they married each other-- and so she found a father at last.

I: Let me take you back to that story of Mrs. Roosevelt coming to Virginia and you riding around with them in the back of the car. Can you tell me anymore about that?

Clark: I just remember her being the most unassuming person that I ever met in my life, and utterly charming. We lived in a little row house and she stayed at a hotel, but she was unpretentious, utterly charming, she was the one person that never changed. Nothing ever went to her head. And no, I guess, you see at that time I was eight years old.

I: Right, you were young then and you couldn't remember.

Clark: You know that Roosevelt built her a house at Hyde Park. And then she built a little furniture factory there and she gave me a doll chair that they built in that furniture factory and my daughter has that now.

I: Did you meet Mrs. Roosevelt later on any other occasions?

Clark: The last time that I saw her I was 28 years old and I had met her first when I was eight years old.

I know somebody who had sent her a wedding invitation to her wedding and she had sent her a present and then when I bumped into her when I was 28 she said, "Are you married yet because I have never gotten a wedding invitation?" And I said, "I would never presume to send you a wedding invitation."

The last time that I saw her she had been appointed by Truman to the United Nations. We had gone to a Governors Conference in New Hampshire and then we came back and stopped by to see the United Nations and Mrs. Roosevelt was there. And that was the last time that I saw her.

But after daddy met her, when she came to make that speech, they became best friends. Anytime he needed somebody to make a speech when he was head of Public Welfare (he would ask Mrs. Roosevelt). She made speeches everywhere. And he would put her next to the most militant Republican that he could find and then it was absolutely fascinating, daddy said, to watch at the end of the meeting she had that man eating completely out of her hand.

I: Because of her personal charm?

Clark: Total charm and no ego, and her interest in people. I mean, and I am sure she and daddy had been talking, but if she had been talking to me, she would have shown interest in me. If she hadn't I wouldn't have gotten that doll chair.

You know that she was not close to any of her children, except Elliott, who was her favorite child and he was the one that was an alcoholic just like her own father.

And then after she died he wrote not a nice book about her and it broke my heart, because she was the most wonderful, unassuming person. And I loved that cartoon about her in the New Yorker that they have of her down in the coal mines and somebody says, "My God there is Mrs. Roosevelt."

Everybody knew that Roosevelt was very much in love with Missy Lehand and so they lived totally separate lives. But they were very congenial. But Roosevelt had this wonderful sense of humor and he loved to play poker, and all of that, but for Mrs. Roosevelt "Life was real and life was earnest." Because of the childhood that she had, that had been so traumatic with the father she adorned, who was an alcoholic, and the mother that had died.

And then she was the "ugly duckling" in the family. She said that, I have a marvelous biography of her I'll lend it to you. She really wasn't happy until she went to Europe and went to school in Switzerland and at this wonderful school she found out that she was a person. Then she started getting very much interested in public affairs and all and became her own person.

I: Do you remember any other particular times that you met Mrs. Roosevelt? Any anecdotes that you could tell me?

Clark: No mainly just watching her, because I never set next to her at a speech. Oh I went to the teas at the White House, and she would talk to me because I was daddy's daughter.

The place that I would have liked to have been was on December the 7th 1941, my mother and father were having lunch at the White House and I was in Chicago and I was listening to the radio and we were having a house party for all these midshipmen, these 90-day wonders and all. And at 1:30 p.m. I was listening to the radio and right in the middle of the symphony they interrupted and talked about Pearl Harbor.

Mother and dad were staying at what became the Roger Smith Hotel. They were going to have lunch at the White House, and I started calling them at 2 o'clock, you know, just frantic. And I at last got them at 5 o'clock, because they kept waiting for President Roosevelt to come to lunch and at last the butler came down and said, "He will not be down for lunch because something is happening in the East." And daddy was thinking that it must be something in the Philippines.

I had two great heroes, my number one great hero is George Marshall and my second one is Edward R. Murrow. And Edward R. Murrow was invited at the same lunch, but when he came in Roosevelt had them bring him right upstairs. So mother and dad didn't meet him until years later in 1948, when I was allowed to pick the speakers for the Governors Conference. We usually had Presidents and Admirals and Generals and things like that. So I picked Edward R. Murrow and Dorothy Thompson. That is when I got to know Edward R. Murrow. And then he and dad became very, very, good friends.

Daddy was there in Germany when Hitler marched in. And they were having lunch at the White House at the time of Pearl Harbor. He was Regent Professor at the University of California in 1966 when they had the first student riots. So Brownie and everybody said to daddy, "For Gods sake don't go anywhere there because everywhere you go there is a disaster!"

I: Ha! Ha! Ha! That's fascinating. Lets go back to Harry Hopkins. You mentioned Harry Hopkins, tell me about Harry Hopkins. Tell me some stories.

Clark: There is one word that describes him: "bastard."

I: Okay.

Clark: When daddy was head of American Public Welfare every time that we turned around the door bell would ring and there was Harry. He would come from New York and he had not been invited for dinner, we didn't know that he was coming, he just arrived and he would say that he was going to spend the night with us.

I: Wow.

Clark: We used to go to Virginia Beach every summer and so Harry said he and Barbara were going on vacation with us to Virginia Beach. It was not suggested that he go there, he was trying to get a job with The American Public Welfare I am sure.

I came home one time, and I guess I was, gosh I am trying to think how old I was then, American Public Welfare, so I would have been about 14. And Robert Maynard Hutchins had invited my dad and my mother to come to the football game and to sit in his box. This was the last year that they had it, when Jay Berwanger got the first Heisman Trophy (1935).

My mother had gotten a new dress and a new coat and was so excited. Harry arrived the night before to spend the night and he called up Hutchins and then said to my dad, "Now Gray wouldn't be interested in a football game and I certainly would, so why don't I go instead?" And I came back from the football game and my mother was sitting in a bay window and tears were streaming. And I said, "What's the matter?" and she said, "Harry took my ticket and went to the football game."

And from then on every time that he walked in the house daddy would say, "Toots here is Harry." and I would say, "I know it," and I would then walk back to my bedroom and wouldn't eat dinner with them that night.

One time he came by in Chicago. And I said, "Harry I am raising rabbits, you must see them on the front porch." And he said, "Clark I don't have to see them I can smell them two blocks away."

But when he would go to Virginia Beach with us, he and Barbara-she was a love--and we would go fishing, he couldn't stand to get in waves, because he would get sea sick. So we would get on a boat, we would charter a boat to go fishing, and we would be there ten minutes and he would throw up and we would have to come back. But he did it for five years.

And he was Mrs. Roosevelt's friend, he was not Roosevelt's at all, Roosevelt didn't know him. And when Barbara died he then married a lady who was Assistant Editor at Vanity Fair or Harpers Bazaar.

He loved to play the races. He loved to play poker, as who didn't, because that was the first game that my children learned and their Grandfather taught them, they were playing poker when they were four years old.

But he married this gal, who couldn't care less about the child that he had by Barbara. So Mrs. Roosevelt had them move into the White House and it was soon after that . . .

Who was that wonderful man that worked for Roosevelt for years, and after he got polio he worked for him when he was Governor in New York, and then he went to the White house and worked with him, and he smoked like a house afire. He was the one who taught Mrs. Roosevelt how to make speeches. Because when Roosevelt was campaigning for President he couldn't go all of these places. He taught Mrs. Roosevelt to make all of these speeches and they became very close, I mean they were good friends anyway, and he is the one that talked Roosevelt into running for Governor even though he had polio. Anyway he died, and when Harry Hopkins moved in and took his place and then he treated Mrs. Roosevelt like dirt.

There is a man named Lewis, that wrote a book on Mrs. Roosevelt, who was a very good friend, and that is the only book that this came out in. But Roosevelt had nothing to do with Mrs. Roosevelt after that. He just, then he became Roosevelt's right hand man--Louie Howe, that's the name. Taking Louie Howe's place. But he broke her heart, because he was so cruel to her and here she was raising his daughter.

I: How about your father and Harry Hopkins? What was their relationship?

Clark: They got along fine. I don't know anybody that my dad disliked. He had this most amazing knack of taking people as they are--you'll see this in these different write-ups. He had no prejudices against anybody, if somebody did a poor job he was terribly disappointed. And he left Social Security because of Winant. He liked Winant as a person, but he didn't like being waked up at 4 o'clock in the morning. As daddy said, "Social Security was great until they hired a bunch of lawyers and they told you all of the things that you couldn't do instead of all of the things that you could do."

He had a consultant, who was a Professor at the University of Chicago, who would meet once a month with them at American Public Welfare and on the Council of State Governments. He had the same guy who would meet with them if he ever needed a lawyer, then he would call George Bogart. And he never had a lawyer on the American Public Welfare staff or on the Council of State Government staff because he said, "All they do is tell you no."

I: So he was frustrated with Winant's indecisiveness?

Clark: Yes. Winant could never make up his mind. He liked him as a person, he thought that he was one of the most peculiar people he ever met and that is what is in this write up about it.

It is fascinating because there is a letter from Brownlow to daddy and it is strictly confidential but I thought now that it didn't have to be so confidential.

Oh I left out one part. Daddy was not planning to go to Social Security. He just helped write the Act and then he went over and Roosevelt gave him the job of selling it. And he went all over the United States making speeches for Social Security and there was something called "Town Meeting Of The Air." Well that was a wonderful program and it was on once a week on different topics, for an hour.

I: Oh yeah, we talked about, but say it again because I didn't get it on the tape.

Clark: We listened to it and somebody, I don't know who, was talking on the other side and was very much against it. And daddy was very much for it. And this one man said to daddy, "Mr. Bane how do we know that Social Security will do what they say, because it is only the government's promise to pay." And that's when my dad said, "Are there ushers here?" And they said "yes." And he said, "Would you all please bring the biggest waste basket you can find and put it at the end of each aisle?" And then he said to the audience, "Now when you all leave all of you put your paper money into those waste baskets, because they have no value at all, it's only the governments promise to pay."

I: Ha, ha! That was great. That was great!

Clark: But anyway he was not planning to work for Social Security at all, and Daddy said that he never liked to stay, I told you, at any job longer than three years.

I: He had been there three years at APW.

Clark: At American Public Welfare. So he had accepted the job to be the head of Political Science at University of North Carolina. When Graham was President, I think he is the best President that they ever had at North Carolina. But anyway we were up in a cottage, with friends--Simeon Leland was on a lot of these committees when they were doing Social Security and so you will be reading about him, and he taught at the University of Chicago and later at Northwestern. And they had a place on the lake, but they didn't have a telephone. And we were all sitting on the beach by the lake and all of sudden here comes two cars with lights on the top of one. And two men walk up and one is a policeman and one is a sheriff and they wanted to know if Frank Bane is there? And mother said, "What have you done now?" And they were saying, "You don't have a telephone and the White House, the President, has been trying to get a hold of you for days and he had you tracked down and so will you please come with us so you can talk to the White House?"

I: Wow!

Clark: And then Roosevelt offered him the job as Director of the Social Security Board. And then there was all of this discussion that Brownlow and all these people from the Rockefeller-Spelman foundation would try and get Winant to accept daddy as the Director of Social Security. He thought that there should be two people, and half should be done by one and half should be done by the other.

I: This is Winant's idea?

Clark: That was Winant's idea.

I: Okay.

Clark: And this is his long letter on that. Maurine had sent daddy a copy and said, "Please send it to Columbia, so that Columbia will have the history of this." Even though it was supposed to be confidential. But daddy wouldn't take the job if it was that way, and nobody backed Winant up on that, so daddy was made Director of Social Security.

"As Executive Director of the Social Security Board, Frank Bane has the 'key post' in an organization that has the tremendous task of guarding the welfare of approximately 26,000,000 people. Chairman Arthur J. Altmeyer of the Board is in charge of the general policies but Bane is on the 'firing line' in the fight for security and has to handle the details of the job."

|

I: So then you guys had to relocate from Chicago down to Arlington. Okay. How old were you approximately at that time? This is 1935 I guess.

Clark: I was 15 to 18 years of age. And it was really the most exciting time, because in this article this man said, "You know who did you date and who were your friends among important people?" And I said that it was such a little town that you knew all of the people and I didn't want to give to give him any names.

But I had dated John L. Lewis, the adopted son. John L. Lewis and his wife looked exactly the same--the wife even had a goatee. He was the most disagreeable thing. And the daughter looked exactly the same. That was when women would go and leave their calling cards everywhere and you would go to see his wife--mother didn't drive so I would drive her to all of these teas, so I got to meet John L. Lewis' son. It couldn't have been his real son, because he was blond and medium height and utterly charming, while the rest of the other three were "something."

I will never forget-let's talk about Ickes for a minute. They built a building for Social Security and Ickes got it for the Interior Department. (See Frank Bane's article at the end of this interview.)

He got married a second time to a woman who was much younger than he was. We didn't go to the wedding, but it is such a small town and such a small group down there, that he had all of the people in government to come to a reception picnic at Great Falls, which is a park right outside of Washington. And so when I see Harold Ickes Jr. I think "I saw your mother," he looks like his mother, "I knew you before you were even a sperm."

So who was the one who never forgot a name? Farley! Jim Farley. I met him once when daddy was head of the American Public Welfare and years later I met him in Washington and he said, "Hi Clark how are you?" Imagine remembering a name that far.

I: That was part of his skill as a politician.

Clark: But he never forgot a name. He was a computer with that.

But from the time you were sixteen you were invited to anything in the White House if your parents were invited there. And it was the most fun, because I got to go to the receptions and the balls at the White House.

I called everybody I knew, nearly everybody that I knew had gone in the Senate and all, but I called my Congressman and the few Senators I knew in Washington, to say do not put Roosevelt in the wheelchair in his memorial. That it would just break his heart, because he did everything to cover up and they are going to do it. They had decided to do that.

But when you would go down the White House reception line, and Mrs. Roosevelt knew me, and she would say, "Hello Clark" and all, and then Roosevelt would make you feel that he had been waiting the whole time just for you to get there. He had a charm, I've never seen anybody--remind me later to tell you a story about Henry Kaiser and his wife and Roosevelt-but I have never seen anybody in my life with as much charm as he had.

I'll never forget the first time that I went there they had all of these people from West Point and Annapolis to dance with the single ladies and this one asked me to dance and I danced with others, and anyway he asked my daddy if he could take me home, and when he was taking me home he asked me for dates for three or four big occasions coming up and then he said, "By the way how old are you?" And I said "15" and he said, "Forget it. I'll call you again in a year."

I: That's funny.

Clark: But when daddy was appointed head of Social Security there was a Senator from Virginia named Carter Glass. Carter Glass wanted daddy to give a job to one of his friends and daddy wouldn't do. Have you heard this story before?

I: Yes. But please tell it again.

Clark: And so Carter Glass had daddy's salary cut from ten thousand to nine thousand five hundred. Eventually this was reversed.

I: That was an amazing event.

Clark: How did you hear that story? Maurine must have told you.

I: Yeah that is in Maurine's oral history.

Clark: Because I don't know of anybody else that could have told you.

I: Yeah I think that is in Maurine's oral history, that story. Yeah I have it documented somewhere, absolutely. It is an amazing story, I just can't believe it. I mean that it is amazing on so many levels. It is amazing as a good testament to your father's integrity; but it is amazing because it is a story about politics. It is amazing to think that they could just pass a law to get just one person reduced in salary.

Clark: You know that it is fascinating my dad never made that much money and never cared about money.

When he was Superintendent of Schools he had a secretary and he took her to Richmond when he went to work in Richmond. Her husband had deserted her when her child was six months old and so daddy helped send her child to college, when daddy was head of Welfare in Virginia. And daddy got him a hardship scholarship and paid some of the money at Washington Lee. Her son later became Vice President of Ford Motor Company.

Harry Hopkins had two or three sons by his first wife, and never sent them to college, and daddy got them partial scholarships and then sent them to college--on a salary of eight thousand a year.

I: Wow.

Clark: When he was head of Council of State Governments and Dewey was head of the Governor's Association, he raised daddy's salary --daddy was making 14 thousand--and he raised it to 36 thousand. And daddy had his secretary list all of the Governors salaries and divide them by 48 and he said he wasn't going to make anymore than the average of what all of the Governors made. And so that was 16 thousand and so he took the other 12 thousand and raised everybody on his staff two thousand dollars.

I: Really? That's amazing!

Clark: They were making 14 thousand. His secretary was making 12 thousand, daddy was making 16 thousand.

I: Wow.

Clark: So when he retired from the Council of State Governments he called me up one time and he said, "Toots you wouldn't believe it I am getting all of these phone calls offering me a 100 thousand dollars, 60 thousand dollars, 50 thousand dollars as a lobbyist. If they think that I am going to use my influence they are out of their minds."

So what he did was join a lecture group, they gave lectures to government seminars, there is one in Charlottesville. So then he started lecturing in colleges with this lecture group. And if he ever got money ahead he would help somebody out that needed it. This would drive my mother out of her cotton-picking mind.

I: I imagine that it would.

Clark: Money has never meant anything to me either as a result of this. My kids said that I am the only person that they know that feels like they are a millionaire and yet I take boarders.

He was absolutely amazing in that he was just horrified of how he felt that people "prostituted" themselves as lobbyists, and the number of people that did.

"Probably no Virginian in this generation, in a non-elected position, has had more influence on national affairs than Frank Bane."

|

"No man in American history has worked with so many Governors as has Frank Bane. Certainly none has worked more effectively with them. His modesty is such that the public has heard little about him at these meetings. But we of the Governors' Conference know that the role he has filled for us is above any price."

|

I: Yeah, sure. You mentioned Henry Kaiser, you were going to tell me a story about Henry Kaiser.

Clark: My dad told me three things when I was very little and one was never impose on anybody, never be late, and never give any advice to people when you don't know what you are doing. He said, "Your mother didn't know how to drive a car and yet every time that I had to change a tire, she would always tell me how to do it."

And my children said that they have always loved me because of the fact that I never gave them any advise on anything that wasn't my business.

And so we were going to get back to . . .?

I: Henry Kaiser.

Clark: So anyway I read a book called "Kaiser Makes A Doctor" and he started the first prepaid medical plan.

I had been working in Washington and then I got transferred to Chicago, and it was the first time I went to the University of Wisconsin, for two years. I never even went out there to look at it, but it had eight men to every girl. So that was how I chose it--and it did. It was absolutely fabulous.

My mother said that I was being absolutely selfish to be going there when I could come and live at home and go to the University of Chicago for free, because daddy lectured there also. So I went to the University of Chicago for two years. And I went to work and so I saved enough money and the day after I graduated I hopped a train and went to Washington with two hundred dollars so I could find a job.

I: What did you do? What job did you do?

Clark: Ellen Woodward wanted me to work in her office as her "Girl Friday." And she was the best friend.

I: Where was she at this time?

Clark: She was on the Board of Social Security. And one thing that I swore was that I would never work in any job that I had to get through daddy, because of my connections with daddy, and so she had made a little office and had a miniature desk for me and I worked there for free for two months while I was looking for another job.

And I thought that I was stupid--and I mean everybody thought that I was, because of my grades. I found my grades going through here. When I graduated from the University of Chicago, Robert Maynard Hutchinson stopped the whole procession when it got to Clark Bane and handed me my diploma and said, "Is this possible?"

I: That you had done so well?

Clark: Because I had done so poorly. We didn't think for a minute that I was going to make it. I took a Bachelor of Science and we had an eight hour comprehensive on physics and chemistry and all of these things that I hadn't taken, so I had all of these "D's" and so I mean that I got through just barely, but oh I had a wonderful time though.

So then I went (to look for a job). I couldn't type, but I thought that I could get a job as a clerk. They set up a Central Administrative Services group to handle personnel for all the government agencies. So I went there to get a job as a clerk and they gave us all an IQ test, all fifty of us. When I came back she said to me, "What do you mean you want to be a clerk?" "You got the second highest IQ of the fifty." I said, "You are out of your mind, go and look it over again, because I am not very bright." And the other guy, the one that got the highest IQ, was somebody that had a Ph.D., a young colored man from some colored college--the most brilliant one of all of us.

I was a Personnel Classification Analyst for the Office of Defense Transportation, and then they transferred me to the Chicago office. My mother thought it was terrible that I should take an apartment when there were so few. She thought I should live at home.

My boss one day gave me a low evaluation and I said, "What have I done that is so wrong? My evaluation is not good and the people that I work with think I am great." And he said, "I asked you for a date your Freshman year at the University of Wisconsin and you turned me down."

I: You are kidding!

Clark: And I didn't even remember him, and that made him even madder.

And so after that I was walking down the street and I bumped into a teacher who had taught me Child Development at the University of Chicago and he said that they were setting up a 24-hour nursery school for the children of workers in the Kaiser Ship Yard.

I: Okay.

Clark: And Lois Meeks Stokes was setting it up and she asked me would I be interested in a job? And I said, "Sure. When?" And she said that they want people right away. So I gave two weeks notice and got on the train and went out to Portland, Oregon, having never been there. Doris Kerns Goodwin was talking another time on public radio and she was saying that the 24-hour a day nursing school was Mrs. Roosevelt's idea.

I got there before it opened up and then they had a big open house and I was working with the 2-year olds. Lois Meeks Stokes came from the University of California and wanted to meet the person who had set up this room for the 2-year olds. And so the boss called me in and I met her and she said, "How in the world could you get into a 2-year old's mind like that? That is exactly like how they would go about growing." I said, "That was a 23-year old mind working her head off trying to do it right!"

But you know instead of singing Jack and Jill goes up the hill, I would sing all of the songs with them that they had heard on the radio, and one of them was "Pistol-Packin' Mama." And I was jumping up and down with all the kids on this jumping board, and we were all jumping up and down singing "lay that pistol down babe" at the top of our lungs. So I thought that I was going to be fired pretty soon!

Incidentally as I said, I never got a job that I applied for. So I went over to Kaiser's Hospital in Vancouver, Washington to get all of this material on it, because, as I said, I'd read the book. The Superintendent was kind of a smart-aleck young man named Frank. And he was on the phone for a long time while I was waiting. Then in walks this gray-haired man, soaking wet, looking so down and so unhappy. And Frank put the phone down and said, "Miss Bane, this is Dr. Nagle."

It turned out that Wally Nagle was chief of staff at the hospital. And he was waiting to talk to Frank. He asked me what I was doing and I told him I was working over at the nursery school. He asked me how I liked it. I was working with 2-year-olds, and a lot of them weren't housebroken. So every time I had to change pants, I'd throw up. So half the time, I was lying down with a wet towel on my head. So Wally said, "How would you like to come over here to work?" The nursery school was at Swan Island in Portland, Oregon. And across the river, was Vancouver Ship Yards-they built the baby flattops, the baby aircraft carriers. And Edgar Kaiser was running that.

So anyway, my new job was to be the doctor's bedside manager. Because we had so many patients, and no matter how many doctors we had, it wasn't enough. So my job was to keep the patients happy.

And it was fascinating. I learned to play pinochle. In those days, they had the Arkies and the Okies--the migratory farmers. So we had mainly Okies and Arkies working in the shipyard. Then they needed all the labor they could get, so a lot of colored people came from the south. Well, anybody who was colored who left the south had to be mighty bright, and mighty courageous. Because if you leave Mississippi and go to Oregon or the State of Washington, you were as smart as you could be.

We had integrated housing--the first integrated housing for the workers. And one day a colored minister who worked there came and wanted to know if he could have an appointment with me. And I said, "Sure." And he said, "Miss Bane, would you do me a favor? Would you talk to Mr. Kaiser and ask if we could have segregated housing?" And I said "segregated housing? I have been for you people having integrated housing all my life." And I said, "Why in the world do you want that?" And he said, "We can't stand having our children playing with the poor white trash."