History of SSA 1993-2000

|

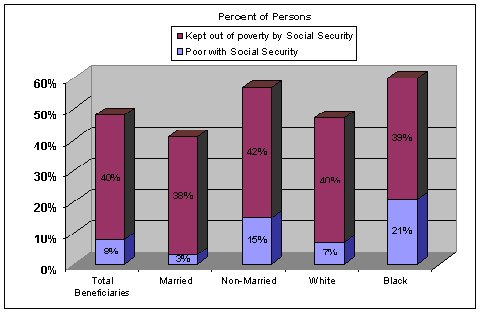

t is fitting that in the final year of the Clinton Administration, Social Security celebrated its 65th anniversary. Sixty-five years ago, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act into law, insuring in his words, “The security of home, the security of livelihood and the security of social insurance.” He was a true visionary and his actions in creating Social Security – along with creation of the rest of the New Deal, helped move this country out of the Great Depression. And President William J. Clinton has not only assured the viability of this great program, but has built on the solid foundation that FDR laid. It’s also ironic that this program, which is an integral part of the very fabric of our nation, thrives today in a time of economic prosperity, proving that Social Security is a timeless program, serving the American people well in all types of economic environments. The Social Security program has become the most successful, most popular domestic program in the nation’s history. This Administrative History is a testament to that legacy by providing a comprehensive picture of SSA’s efforts during the Clinton Administration in administering the Social Security programs. What follows highlights the major issues, significant events, and organizational changes at the Social Security Administration (SSA) during the past eight years. Because of their significance, information about the establishment of SSA as an Independent Agency and the long-term solvency of the Social Security program are presented as separate chapters. During the eight years, SSA made great strides in addressing the priorities established by its Commissioners: educating the public about the value of the Social Security program and its long-term challenges, as well as its role in personal, financial planning; assuring program integrity; providing responsive service to the public; improving the administration of its Disability and Supplemental Security Income programs; strengthening its long-range planning and policy making processes; and investing in its employees. This Administrative History will hopefully be of interest to historians, biographers and scholars from many disciplines. It provides a narrative compiled from the viewpoint of people who were actively involved in administering the Agency’s policy initiatives. In addition, a detailed chronology of major SSA events that occurred between 1993 and 2000 is included as Exhibit 1. SSA administers one of the largest and most complex Federal Government programs. The Agency provides social insurance coverage to more than 153 million workers, the self-employed and their families. The Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) and the Disability Insurance (DI) programs (commonly known as Social Security) are based in Title II of the Social Security Act. More than 48 million persons received monthly Social Security benefits, totaling in excess of $33 billion in June 2000. [1] Of these, more than 31.5 million were retired persons and their family members, but Social Security is also much more than just a retirement program. More than seven million family members of deceased workers and approximately 6.6 million disabled workers and their dependents received monthly Social Security benefits. The Social Security program is, in fact, an intergenerational compact that has become America’s family protection plan. Because of these programs, people in this country are doing much better economically. For example, since 1959, the poverty rate among elderly Social Security beneficiaries has declined by 72 percent, from 35.2 percent in 1959 to 9.7 percent in 1999, largely due to Social Security benefits. [2]

Social Security’s Role in Reducing Poverty for Persons Aged 65 and Older – 1999 [3]

SSA is also responsible for the management of the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. SSI, based in Title XVI of the Social Security Act, is a means-tested program that pays monthly checks to people who have limited assets and income, and who are 65 or older, blind, or disabled. Under Title XVI, about 6.6 million people received monthly SSI payments totaling $2.7 billion in October 2000. [4] Executive LeadershipThe original Social Security Act established a Social Security Board (Board) as an independent agency, comprised of three members appointed by the President. [5] The Chief Executive was the Chairman of the Board, who reported directly to the President. The Board was abolished in 1946 and replaced by the Social Security Administration. Since 1946, a single Commissioner has headed SSA. Thirteen persons held the position of Commissioner between 1946 and 2000. As the Chief Executive Officer, the Commissioner represents SSA, both internally and externally, as its leader. In this role, the Commissioner must be able to communicate effectively to the Congress and to the public. The Commissioner must lead with high energy and boundless enthusiasm, give employees a sense of purpose and direction, and plan for success. Commissioner Shirley Chater served as Commissioner during most of President Clinton’s first term. Commissioner Apfel led the Agency as its first confirmed Commissioner as an Independent Agency and served as Commissioner of Social Security during most of the President’s second term. [6] Shirley S. Chater, Commissioner of Social Security:

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Program Management

| SSA's

Mission "To promote the economic security of the nation's people through compassionate and vigilant leadership in shaping and managing America's Social Security programs." |

The Agency’s new mission statement, formulated in 1997, reflected SSA’s traditional role in American life and its expanded role as an independent agency. SSA had always taken pride in paying “the right check to the right person at the right time” and in treating each customer with care and compassion. The new mission signaled that these ideas were still important. It was clearly directed toward producing an outcome (“To promote the economic security of the nation’s people…”). This supported the Government Performance and Results Act’s mandate for a Government focused on producing outcomes rather then outputs.

SSA’s stewardship of the Social Security trust funds and general revenues has always been an important part of the Agency’s mission. The new mission elevated this traditional stewardship to one of “vigilant leadership in…managing” funds entrusted to the Agency. As an Independent Agency, SSA’s mission included, for the first time, leadership in the shaping of America’s Social Security programs through active policy development, research, and program evaluation.

In January 1994, under Commissioner Shirley S. Chater’s leadership, SSA revised the three Agency-level strategic goals established in 1991 [8] as follows:

· Rebuild Public Confidence in Social Security;

· Provide World-Class Service; and,

· Create a Nurturing Environment for SSA Employees.

In 1997, the Agency’s 1997-2002 Strategic Plan [9] created five goals. These goals elaborated on the 1994 goals and reflected SSA as an Independent Agency. They encompassed all of the Agency’s program activities, addressed the universe of competing needs of the wide variety of SSA stakeholders, and gave meaning to the work of every Social Security and Disability Determination Service (DDS) employee. The five strategic goals are listed below.

| 1. To promote valued, strong, and responsive Social Security programs and conduct effective policy development, research, and program evaluation. |

The first goal summarizes the Agency’s strategy to ensure that its programs provide a base of economic security for workers, the aged, and disabled, now and in the future. Critical analysis, research, and evaluation are integral to SSA’s role in shaping the programs so that they evolve to take account of future demographic and economic trends. Decisionmakers need information on program challenges and the impact of options for strengthening the programs to meet the current and future needs of beneficiaries and workers.

This strategic goal uses a mix of program outcomes and performance goals that measure the extent to which critical information is available for use by decisionmakers. The mix of goals reflects the fact that the effects of policy development, research, and program evaluation are difficult to quantify and measure, since many factors affect program outcomes related to a change in policy.

| 2. To deliver customer-responsive, world-class service. |

The second goal has guided the actions of SSA and DDS employees throughout SSA’s history. It demonstrates how the Agency places its customers and their needs first.

SSA has a longstanding reputation as the premier Government agency for providing customer service. As it looks to the future, SSA aims to provide the best services that organization – public or private – could provide.

| 3. To make SSA program management the best in business, with zero tolerance for fraud and abuse. |

The third goal emphasizes that SSA has a responsibility to pay benefits accurately and be a good steward of the money entrusted to its care. SSA set very high standards because it believes that the public deserves the highest possible level of performance consistent with fiscal responsibility.

SSA will deter fraud and make sure that those involved are accountable, whether the public or its employees commit it.

| 4. To be an employer that values and invests in each employee. |

SSA’s greatest strength lies in the attitudes, skills, and drive of its employees. The fourth goal recognizes that the employees of SSA and the DDSs are key to achieving its goals and objectives. It also reflects SSA’s conviction that employees deserve a professional environment in which their dedication to the SSA mission and to their own goals can flourish.

The focus of this goal is to ensure that SSA continues to hire and retain the highly skilled, highly performing, and highly motivated workforce that are critical to achievement of its mission. While SSA’s workforce is one of its most valuable assets, technology is also important because it is essential to the effectiveness of that workforce and indispensable to the success of serving the public. The Intelligent Workstation/Local Area Network (IWS/LAN) is the linchpin for both SSA’s customer service program and its entire business approach. [10]

| 5. To strengthen public understanding of the Social Security programs. |

One of SSA’s basic responsibilities to the public is to ensure that people understand the benefits available under the Social Security programs. The fifth goal ensures that people can make informed choices as they plan for their future.

SSA publishes more than 100 pamphlets, newsletters, booklets, and other information about its programs, policies, and procedures so that the public can be fully informed about its programs. SSA also produces information in audio, video, and electronic media. In addition, SSA produces about 20 administrative publications. Most of these publications are also available to the public on SSA’s website (www.ssa.gov). In addition, SSA began mailing Social Security Statements (Statements) to all workers 25 years of age or older starting in October 1999. The Statements assist all Americans in their personal financial planning.

These five strategic goals form the framing structure for five chapters of SSA’s Administrative History. The chapters capture and highlight the major issues, significant events, and organizational changes at SSA during the Clinton Administration.

SSA Faces Significant Challenges

The eight years of the Clinton Administration were eventful ones for Social Security. SSA faced significant programmatic challenges in the 1990s. The major ones included the long-range solvency of the Social Security trust funds, the disability claims process, growing disability caseloads and related return-to-work efforts, and the management of the SSI program. Sixteen pieces of significant legislation impacting on Social Security were enacted, including the Independent Agency legislation signed by President Clinton in August 1994. The Agency’s 2010 Vision was released outlining SSA’s efforts to plan for the future. Social Security reform was the subject of the first-ever White House Conference on Social Security in December 1998, and was the centerpiece of public debate during the 2000 Presidential campaign. The disability programs drew widespread attention as the Agency worked to improve its services to disabled applicants, and Congress wrestled with disability policy issues involving payments to noncitizens and children that were contained in the welfare reform bill which became law in 1996. Reports on fraud and abuse in the media and from the General Accounting Office (GAO) and SSA’s Inspector General raised questions about the management of the SSI program. GAO placed the SSI program on its “High Risk” list in February 1997 on the basis that the program was susceptible to fraud and abuse. Sending personal statements (called Social Security Statements) verifying individuals’ earnings history and estimates of benefits to all workers, 25 and older, began in 1999. They served to educate the public about the benefits available to them under the Social Security programs. These statements, more than 133 million in the first year, are considered the largest customized mailings by a Federal agency. Throughout the eight-year period, SSA received high marks from many sources, both public and private, and was recognized as a highly capable and well-run agency.

SSA Enters the 21st Century

2010 Vision

SSA is preparing now for the baby boom generation and the expected growth in disability and retirement workloads, newly evolving technologies and public expectations about quality service. To plan for the future effectively, Commissioner Apfel created a 2010 Vision initiative for the Agency. The 2010 Vision, formally released by Commissioner Apfel on September 7, 2000, was developed with input from a wide variety of stakeholders.

The mission of SSA—to promote the economic security of the nation’s people—can only be accomplished through fulfillment of its fundamental responsibilities to administer effective programs, provide quality service, ensure program integrity, educate the public, and value and invest in its workforce. Each critical responsibility poses challenges to the Agency, but it was the service challenge, resulting primarily from the factors noted below, that became the focus of the 2010 Vision.

· By 2010, workloads will swell to unprecedented volumes. The most significant factor contributing to this change will be the aging of the baby boom generation (those born in 1946 through 1964).

· Along with the workload increase, the incredible pace of technological change will have a profound impact on both customer expectations and SSA’s ability to meet those expectations.

· More than one-half of the current Federal workforce may be gone by 2010, over 28,000 SSA employees will be eligible to retire, and another 10,000 are expected to leave the Agency for other reasons. This retirement wave will result in a significant loss of institutional knowledge. The DDSs will also experience a retirement wave.

SSA’s 2010 Vision presented a picture of a changed Agency: one that, along with its DDS partners, has an integrated service delivery network using redesigned and streamlined processes supported by state-of-the-art technology. It presented an Agency that provides service comparable to or better than the private sector; an Agency that is considered an “employer of choice”—retaining, attracting, and developing a highly skilled and highly graded workforce providing world-class service.

The process of creating the Vision has been completed. The far more difficult process of pursuing the Vision is just beginning. In addition to obtaining the human resources and capital investments needed to achieve the Vision, SSA will link and sequence the Agency’s strategic planning and budget processes to the Vision to ensure that resources and priorities are properly aligned. Early initiatives will be announced in the areas of technology, training, upgrading of skills and positions, and activities that will move it toward greater operational flexibility.

SSA will engage in more detailed service delivery planning. The Agency will map out more specifically its business requirements—how its core business processes must change and organizational functions must adapt to realize the Vision. From the business requirements, SSA will outline how the Agency’s human and information technology resources must evolve to support new ways of delivering service. SSA’s five-year human resource plan will build upon the new business requirements and specify the target positions and skills that will be needed, and the action plans and timelines for delivering these resources. Likewise, its information technology plans will build upon these same requirements to specify systems infrastructure goals and the action plans and timelines for achieving them.

Policy Debate

Program Solvency

| Spending

exceeds tax revenues in 2015 Combined OASDI trust funds peak in 2024 Combined OASDI funds become exhausted in 2037 |

SSA is looking to the future and the preservation of the Social Security Program. Americans are living longer, healthier lives. In addition, the baby-boom generation is nearing retirement. These demographic changes create long-term funding issues for Social Security.

Currently, tax revenues to the Social Security system exceed benefit payments, and the system is building large reserves that are held in the trust funds. Under the March 2000 Board of Trustees Report, benefit payments will begin to exceed tax collections in 2015. [11] Total income (including interest earnings on the trust funds) will exceed expenditures through 2024. It is estimated that beginning in 2025, trust fund assets would have to be redeemed to cover the difference until the assets of the combined funds are exhausted in 2037. At that time, revenues will support only about 72 percent of benefits due.

In both his 1999 and 2000 State of the Union addresses, the President proposed plans to deal with the long term financing issues facing Social Security. His 2000 plan would extend solvency from 2037 to 2057. Other plans to ensure long-term program financing also have been proposed. The Solvency chapter discusses the efforts to resolve the long-range financing issue.

Improvements to the Disability Claims Process

SSA strives to deliver the highest levels of service by making fair, consistent and timely decisions at all adjudicative levels. However, applicants for disability benefits sometimes find the process complex, fragmented, confusing, impersonal, and time consuming. Some also perceive the process as one in which different decisions are reached on similar cases at different levels of the administrative review process, thus requiring applicants to maneuver through multiple appeals steps.

SSA’s current disability claims process consists of an initial determination by a Federally funded, but State-administered, DDS and up to three levels of administrative appeals if an individual is dissatisfied with the decision: (1) reconsideration, (2) hearing before a Federal administrative judge, and (3) an Appeals Council review. If the Appeals Council affirms the denial, the applicant can begin a civil action in a U.S. Federal district court.

To remedy the concerns and perceptions about the determination process, SSA implemented a plan beginning in 1993. The plan sought to improve the disability claims process from initial contact through final administrative appeal in order to improve service delivery to the millions of individuals filing for or appealing disability claims every year. Two major areas of focus have been process unification and modifications to the disability claims process.

The goal of process unification, begun in 1993, was to foster similar results on similar cases at all stages of the process through consistent application of laws, regulations, and rulings. The initiatives have shown promise. Over the last several years, there has been a decline in the allowance rates at the hearing level and an increase in the initial allowance rates at the DDS level. This trend is consistent with SSA’s objectives to make the correct decision as early in the process as possible.

SSA tested various process improvements to determine what changes would help provide better customer service. Several different modifications were piloted both singularly and in combination. Data from the most significant testing model, the full process model, showed that increasing examiner authority and responsibility, using medical examiner expertise better, and increasing interaction with claimants at the initial level resulted in better quality and customer service. The full process model testing began in 1997 in eight states. The Program Changes chapter contains detailed information about SSA’s efforts to improve the disability process.

Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999

The Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999 was enacted on December 17, 1999, with many of its important provisions effective January 1, 2001. The first provision of the law took effect in October 2000 and enabled many disability beneficiaries to be eligible for expanded Medicare coverage. This was a great improvement for disability beneficiaries who otherwise would have had to decide between working or keeping the health coverage they needed.

In 2001, SSA will begin a three-year national rollout of the “Ticket to Work and Self-Sufficiency” program. Implemented in a few States at a time, the program will give beneficiaries greater access to rehabilitation and employment services. Also, it will be easier for former beneficiaries who are working to receive benefits if they can no longer work because of their disabilities.

The new law focuses on many of the barriers that have long kept

people with disabilities out of the workforce. SSA expects

to make great progress in the area of work incentives, so that

those individuals with disabilities who want to work can do so.

Management of the SSI Program

The SSI program provides benefits to approximately 6.6 million financially needy recipients who are aged, blind or disabled. Like other means-tested programs that respond to changing circumstances of individuals’ lives, the SSI program presents challenges to ensure that it is administered efficiently, accurately, and fairly.

Over the years, legislation and court decisions have made the SSI program even more complex. As complexity has increased, so has the proportion of SSA staff resources devoted to program administration. Although the number of SSI recipients is less than 15 percent of the number of OASDI beneficiaries, SSA devoted 37 percent of its administrative budget to SSI in Fiscal Year 2000. The relatively high level of administrative costs is generally attributable to the frequent interaction required between field office staff and many SSI recipients.

SSA continues to face challenges in administering the complex provisions of the SSI program. [12] In an effort to deal with these challenges, Commissioner Apfel undertook a major initiative in 1998 to strengthen management of the SSI program. In October 1998, SSA issued the first management report on the SSI program, detailing the Agency’s aggressive plans: (1) improve payment accuracy, (2) increase continuing disability reviews (CDRs), (3) combat fraud, and (4) collect overpayments. [13] This multifaceted approach to improving SSA’s administration of the SSI program remains one of the agency’s highest priorities. SSA executed several of the initiatives outlined in the report, such as new computer matches and processing more eligibility redeterminations.

| 1. To promote valued, strong, and responsive Social Security programs and conduct effective policy development, research, and program evaluation. |

RETIREMENT EARNINGS TEST (RET)

Another significant change in Social Security during the Clinton Administration was the repeal of the Retirement Earnings Test (RET) which helped retirees to supplement their Social Security benefits with earnings. On April 7, 2000, President Clinton signed The Senior Citizens’ Freedom to Work Act of 2000 eliminating the retirement earnings test for beneficiaries aged 65-69, upon reaching their Normal Retirement Age.

Prior to the change, earnings above a certain limit would affect benefits. Although benefits withheld under the retirement earnings test were roughly offset by higher benefits later on, many people perceived the retirement earnings test as a tax on their earnings. Eliminating this perceived disincentive was expected to lead to a modest increase in work activity among some retirees.

As a result of this legislation, about 800,000 beneficiaries age 65-69 and 150,000 auxiliary beneficiaries, who previously had lost some or all of their benefits under the test, now receive full benefits. About 400,000 beneficiaries in this group were reinstated and received retroactive payments averaging $3,500 per person. SSA paid a total of $1.5 billion in refunds just three weeks after the legislation was signed into law.

Major Legislative Changes

The following chapters discuss, in detail, the impact of the legislative changes. The annual highlights of Social Security legislation enacted during the Clinton Administration included the following:

1993 Amendments

Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 (P.L. 103-66):

· Made up to 85 percent of Social Security benefits subject to the income tax for persons whose income plus one-half of their benefits exceed $34,000 (single) and $44,000 (couple).

· Required States to pay fees for Federal administration of their supplementary SSI payments.

Unemployment Compensation Amendments of 1993 (P.L. 103-152):

· Increased temporarily from three years to five years the period during which the income and resources of an immigrant’s sponsor will be “deemed” to the immigrant for purposes of determining the immigrant’s eligibility for and the amount of SSI benefits.

1994 Amendments

Social Security Independence and Program Improvements Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-296):

· Established the Social Security Administration as an independent agency, headed by a Commissioner appointed by the President to serve a six-year term.

· Placed new restrictions on Social Security disability insurance and SSI benefit payments to individuals disabled solely by drug addiction and alcoholism (DAA).

· Required SSA to perform a minimum of 100,000 CDRs of SSI recipients each year during FY 1996 through FY 1998.

Social Security Domestic Employment Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-387):

· Raised the threshold for coverage of domestic employees’ earnings paid per employer from $50 per calendar quarter to $1,000 in calendar year 1994. For calendar years after 1995, this amount increased in $100 increments as average wages increase.

· Allocated a greater portion of the OASDI tax rate to the DI trust fund beginning in 1994.

· Authorized SSA to use certain delinquent debt collection procedures available to other Federal agencies.

Social Security Act Amendments of 1994 (P.L. 103-432):

· Provided that the criteria used for determining disability of children would apply to any individual who is under age 18 (i.e., individuals who do not meet the SSI definition of a child because they are married or the head of a household).

Uruguay Round Agreements Act (P.L. 103-465):

· Permitted persons to request voluntary withholding from certain Federal payments, including Social Security benefits, for income tax purposes.

· Increased from 50 to 85 percent the amount of Social Security benefits that are subject to mandatory Federal income tax withholding because they are paid to nonresident immigrants.

· Required that in order to claim a dependency exemption for Federal income tax purposes, a taxpayer must include the Tax Identification Number or Social Security Number for that dependent on his or her return, regardless of age.

1996 Amendments

Contract With America Advancement Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-121):

· Gradually raised the annual earnings exempt amount for beneficiaries who have reached normal retirement age to $30,000 by 2002.

· Prospectively denied Social Security and SSI disability benefits to individuals disabled solely due to DAA and required SSA to perform medical redeterminations for such individuals who appealed their termination of benefits.

· Required representative payees for Social Security disability or SSI disability individuals who have a DAA condition and who are incapable of managing their benefits, and required treatment referrals for those on the rolls with DAA conditions.

· Authorized additional funding for CDRs and disability redeterminations for FY 1996 to FY 2002; and required annual reports to Congress on CDRs for those years.

Omnibus Consolidated Rescissions and Appropriations Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-134):

· Provided additional funding for processing CDRs and continued investments in automation.

· Required recurring Federal payments, including Social Security and SSI benefits (with exceptions), to persons who begin to receive them after July 1996 to be paid by electronic funds transfer.

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-193):

· Prohibited the payment of Social Security benefits to any noncitizen in the U.S. who is not lawfully present in the U.S. (as determined by the Attorney General).

· Prohibited SSI eligibility for noncitizens with several exceptions.

· Changed SSI eligibility based on childhood disability and required SSA to conduct redeterminations on SSI children on the rolls.

· Provided for incentive payments from SSI program funds to State and local penal institutions for furnishing information (date of confinement and certain identifying information) to SSA, which results in suspension of SSI benefits.

An Act making omnibus consolidated appropriations for FY 1997 (P.L. 104-208):

· Providing funding for SSA expenses and separate funding for automation, as well as continuing disability reviews.

· Added a new category to the definition of “qualified alien.”

1997 Amendments

Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-33):

· Expanded the categories of noncitizens that may be eligible for SSI.

· Extended the timeframes for receiving SSI for certain aliens subject to time-limited benefits as provided in the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996.

1998 Amendments

Noncitizen Benefit Clarification and Other Technical Amendment Act of 1998 (P.L. 105-306):

· Extended permanently the eligibility of all noncitizens that were receiving SSI benefits when the welfare reform law was passed in August 1996 (P.L. 104-193).

· Authorized SSA to collect SSI overpayments by offsetting Social Security benefits.

1999 Amendments

Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-169):

· Authorized the Commissioner to employ certain statutory debt collection practices to collect delinquent accounts.

· Added a new title VIII (Special Benefits for Certain World War II Veterans) to the Social Security Act to provide monthly benefits for each month certain qualified World War II veterans reside outside the United States.

Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999 (P.L. 106-170):

· Directed the Commissioner of Social Security to establish a Ticket to Work and Self-Sufficiency Program. A disabled beneficiary may use a ticket issued by the Commissioner to obtain employment and vocational rehabilitation services or other support services at SSA’s expense.

· Established a Work Incentives Advisory Panel and a Work Incentives Outreach Program and authorizes the Commissioner to make payments to protection and advocacy systems established in each State.

· Eliminated work activity as a basis for conducting continuing disability reviews for individuals entitled to disability benefits for at least two years.

2000 Amendments

Senior Citizens’ Freedom To Work Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-182):

· Eliminated the Social Security retirement earnings test in and after the month in which a person attains normal retirement age.

Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-386):

· Noncitizens, regardless of their immigration status, who are victims of “severe forms of trafficking in persons in the United States”, shall be eligible for SSI to the same extent that refugees are eligible.

A Well-Run Agency

The Administration and the Congress have challenged Federal agencies to manage more efficiently for results and accountability. The Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO), the Government Performance and Results Act of 1993 (GPRA), and the Government Management Reform Act of 1994 (GMRA) are all designed to promote a more effective federal government. In addition, the National Performance Review, under Vice President Gore’s direction, is aimed at making government work better and cost less. SSA strongly supported these efforts as important and necessary steps to improving its management. According to the General Accounting Office, SSA has surpassed many other Federal agencies in these areas. SSA is ahead of many Federal agencies in managing for results and improving financial accountability. [14]

Administrative Costs

The cost to administer the Social Security Program is extraordinarily low – less than one percent of net payroll contributions from taxpayers. In FY 1999, the total cost was $3.36 billion. [15] These costs included employees’ salaries and benefits, maintaining office buildings, office supplies, office automation systems, payments to the states to administer the DDSs, and every other expense related to the program.

In FY 1999, the administrative costs of the Retirement and Survivors Program were 0.5 percent of contributions to the OASI Trust Fund, and the administrative costs of the Disability Program were 2.5 percent of contributions to the DI Trust Fund. The combined costs of the OASDI Programs were .07 percent of contributions to the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds.

Net Administrative Expenses as a Percentage of Contribution Income and of Benefit Payments, by Trust Fund, Fiscal Years 1995-1999. [16]

|

OASI Trust Fund |

DI Trust Fund |

OASI and DI Trust Funds, combined |

||||

|

Fiscal Year |

Contribution Income |

Benefit Payments |

Contribution Income |

Benefit Payments |

Contribution Income |

Benefit Payments |

|

1993 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

3.0 |

2.8 |

0.9 |

1.0 |

|

1994 |

.6 |

.7 |

3.1 |

2.8 |

.8 |

.9 |

|

1995 |

.6 |

.6 |

1.6 |

2.7 |

.8 |

.9 |

|

1996 |

.6 |

.6 |

1.9 |

2.5 |

.8 |

.8 |

|

1997 |

.6 |

.6 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

.8 |

.9 |

|

1998 |

.6 |

.6 |

2.7 |

3.3 |

.9 |

1.0 |

|

1999 |

.5 |

.6 |

2.5 |

3.0 |

.7 |

.9 |

SSI payments and related administrative expenses are financed from general tax revenues, not the Social Security Trust Funds. In FY 1999, the administrative costs of the SSI program were 8.4 percent of benefit payments. The combined administrative costs of the OASDI and SSI programs were 1.7 percent of benefit payments in FY 1999. [17]

Chief Financial Officers Act (CFO) of 1990 and the Government Management Reform Act (GMRA) of 1994

The major purposes of the CFO Act were to correct longstanding shortcomings in financial systems, internal controls, and the use of assets, and to produce more reliable and useful financial information. The purposes of GMRA were to provide a more effective, efficient, and responsive government through a series of Federal management reforms, primarily in human resources and financial management. It builds on the CFO Act.

SSA was a leader among Federal agencies in producing complete, accurate, and timely financial statements as required by the CFO Act and GMRA. The Agency had a 13-year history of issuing audited financial statements, and from FY 1991 to the present, has had the distinction of being the first Federal agency every year to issue its audited financial statement. Since FY 1994, SSA’s financial statements have received an unqualified opinion. The financial statements were prepared in accordance with requirements of the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board, the Office of Management and Budget, the Chief Financial Officers Act and other relevant statutes.

SSA’s financial statements demonstrated that the Agency operated in a business-like manner, properly exercised its stewardship role and fiduciary responsibilities for the Social Security trust funds, and determined the adequacy of the Social Security trust funds, both now and well into the future. SSA’s financial statements were comprehensive and covered all SSA-administered programs.

In 1999, in partnership with the Association of Government Accountants, the Chief Financial Officer’s Council established the Certificate of Excellence in Accounting Reporting awards program to recognize the importance of accountability reporting in improving Government operations. SSA was one of only two Federal agencies to receive the first-ever Certificate of Excellence in Accounting Reporting in its inaugural year. (The other agency was the National Aeronautics and Space Administration). And, once again, in 2000, SSA was one of two Federal agencies to receive the Certificate, sharing the honor with the National Science Foundation. The Certificate was the highest form of recognition in Federal Government financial management reporting and represents a significant accomplishment for SSA. It was evidence of the fair presentation of the programmatic and financial affairs of a Federal agency.

Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993

GPRA sought to shift the focus of government decisionmaking and accountability away from a preoccupation with the activities performed (outputs) to a focus on the results, service quality, and customer satisfaction of those activities (outcomes). Federal agencies were held accountable for achieving program results.

In October 1997, SSA published Keeping the Promise, the Agency’s third strategic plan (ASP), and the first under GPRA. [18] It is also the first strategic plan since SSA became an independent agency in 1995. The ASP was developed with broad input from internal and external stakeholders, and served as the focal point for a major communications effort to employees throughout the Agency.

In developing the ASP, SSA not only looked at its traditional role of administering the Social Security programs, but also at its new status as an independent agency. While its emphasis remained on a longstanding commitment to quality, service and effective program administration, the Agency also acknowledged its broadened role in providing program leadership.

SSA’s Accountability Report for FY 1999 included its first Annual Performance Report required under GPRA. [19] It contained actual performance achieved in FY 1999 compared with its performance targets. During FY 1999, SSA was able to meet 60 percent of the FY 1999 goals.

National Performance Review (NPR)

The National Performance Review, now known as the National Partnership for Reinventing Government (NPR), was the Clinton Administration’s core effort to reform the Federal Government during most of the last decade. SSA has worked closely with NPR on improving and reinventing the way it does business. Commissioners Chater and Apfel committed SSA to the central NPR tenets – putting people first, adopting best-in-business service standards, and pursuing innovative changes that enable the Agency to “work better and cost less.” Customer-responsive service and maintaining program integrity figured prominently in SSA’s strategic goals and were supported by numerous specific objectives and measures.

Hammer Awards

Vice-President Gore’s Hammer Award honors teams who worked to improve customer service and free federal government of useless rules and red tape. Since 1994, SSA had been honored with 81 Hammer Awards. Some of these efforts were one-time-only projects; some were ongoing and have developed further over the years; and some were prototypes that have been replicated in other parts of the country.

Maxwell School Recognition

SSA was ahead of most agencies in managing for results. The Clinton Administration identified 32 Federal agencies as having a “high impact” on the American public. The Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University (Maxwell) rated the performance of 20 of the Federal agencies in 1999 and 2000. SSA received the highest marks among the 20 Federal agencies. SSA received an overall survey rating of “A” – only one of two agencies to do so. (The other agency was the Coast Guard.) The categories were financial management, human resources, information technology, capital management, and managing for results. The Maxwell report described a bright management picture at SSA. Social Security’s emphasis on efficient administration and service delivery was what won it high marks.

SSA’s National 800-Number

SSA’s National 800-Number Network operation was the most active in the Federal Government and one of the largest 800-number networks in the nation. SSA has 36 teleservice centers located throughout the country. The 800-number is the initial contact for a large percentage of SSA’s customers and receives an average of 65 million calls a year.

In April 1995, SSA was rated as the best telephone customer service from a list of nine “World Class” service organizations in an unsolicited study. Dalbar, Inc., an outside independent financial firm, rated eight private companies (Federal Express, AT&T Universal Credit Cards, Nordstrom, Southwest Airlines, L. L. Bean, Disney Companies, Saturn Corporation and Xerox) along with SSA in three qualitative areas: the attitude, accommodation, and knowledge of their representatives; and two quantitative ones: ring time and time on hold. SSA ranked number one in the first three categories, but lost points for keeping callers on hold. SSA still rated number one because of the exceptionally courteous, knowledgeable, and efficient service that callers received after reaching the Agency.

CIO Magazine

In 2000, SSA was the only major Federal agency named a “2000 CIO-100 honoree” by CIO Magazine. SSA was cited along with such major corporations as Amazon.com Inc., Chase Manhattan Corp., Ford Motor Co., Marriott International, and Intel Corp. SSA was recognized for demonstrating an innovative and sophisticated customer service approach that made the customer central to its business.

Y2K

Preparing for the change of century date – from 1999 to 2000 – was one of the biggest challenges ever to face the technology industry. SSA recognized the potential impact of the Y2K problem as early as 1989 and began early efforts to ensure that the January 2000 Social Security benefits were issued and delivered timely. The General Accounting Office, in 1999, recognized the Agency as a Federal leader in addressing Y2K readiness. [20]

SSA first noticed the year 2000 problem in 1989 when a system “broke.” It was a system that tracked repayments of people who owed SSA money because they were overpaid. Someone in a Social Security field office tried to input a repayment schedule out to the year 2000. The system abended, which meant it came to an abrupt ending. It didn’t work. SSA did a work-around to get the system back up manually. When the agency saw what went wrong, it realized that other systems were going to break. SSA then set up pilot projects to get an idea of the magnitude of the problem. [21]

President Clinton announced at an event at the White House on December 28, 1998, that the Social Security Administration had completed its preparations for the Year 2000 – a full year ahead of schedule, ensuring the government’s ability to deliver benefit checks to millions of Americans into the new millennium without computer problems. “The Social Security system is now 100 percent compliant with our standards and safeguards for the year 2000,” the President said.

SSA worked closely with the Treasury Department, Federal Reserve Bank, and the U.S. Postal Service to ensure that the Social Security and SSI benefit payments due in January 2000 were paid on time. Service to the public continued without interruption as the century date changed.

Tragedy

On April 19, 1995, at 9:02 a.m. Central Time, SSA experienced its greatest tragedy in the terrorist bomb attack on the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The Social Security office was located on the first floor of the building. Sixteen SSA employees were among the168 people who lost their lives.

The Agency established a memorial garden at its national headquarters in Baltimore to honor the SSA victims who died in the explosion. A committee of management, union, headquarters, and field employees, including a survivor of the blast, helped design the symbolic display, which captures SSA’s sense of loss.

President Clinton, in his 1996 State of the Union address, identified Richard Dean as an Oklahoma City Social Security employee who joined First Lady Hillary Clinton in her box at the event. The President recognized Richard for saving the lives of three women. He applauded him for “both his public service and his extraordinary personal heroism.” The President went on to say that Richard was forced out of his office when the government shut down. “And the second time the Government shutdown, he continued helping Social Security recipients, but he was working without pay.”

Government Shutdown

In the fall of 1995, the nation experienced an unprecedented event. Due to a budget deadlock in Congress, the Federal Government shutdown twice. The first shutdown was from November 14, 1995 through November 19, 1995, and the second was from December 16, 1995, through January 5, 1996.

The four-day furlough in November 1995 significantly impacted the Agency’s service to the public. SSA’s contingency plan allowed for the retention of 4,780 employees, while the other 61,415 were placed in furlough status. The American public was unable to conduct its business with SSA, and the effect of the shutdown was felt immediately. During the second day of the shutdown, President Clinton announced that Commissioner Chater had directed employees in direct service positions be recalled to work. A continuing resolution was passed and all federal workers returned to work on Monday, November 20, 1995.

The second shutdown, which began December 16, 1995, was the longest in history. Based on the experience during the November lapse in appropriations and the loss of four full days of production time, any further interruption in service would have had devastating long-term impact on SSA’s ability to process claims for benefits. Therefore, 55,000 direct service employees continued to report to work, and all other employees remained furloughed. Approximately 11,000 employees remained in furlough status. On January 5, 1996, President Clinton signed a continuing resolution through January 26, authorizing the immediate return of all Federal civilian employees affected by the lapse in appropriations.

The Gift Endures

In 1935, while there were long debate and votes on many amendments, the Congress passed the Social Security Act by an overwhelming majority. In the House, the vote was 372 yeas, 33 nays and 25 not voting. The vote in the Senate was equally positive, with 77 yeas, 6 nays and 12 not voting. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Act into law on August 14, 1935. Despite the strong support, there was vocal opposition to the Act, both in the Congress and externally. The minority members of the House Ways and Means Committee said it would impose a crushing burden upon industry and upon labor. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers opposed the bill. It became an issue in the1936 Presidential election. The unsuccessful Presidential candidate alleged that Social Security was “a fraud on the working man” and a cruel hoax. [22] The naysayers questioned the constitutionality of the Act and predicted Social Security’s demise. But the program outlived its early detractors and, during the Clinton Administration, Social Security celebrated its 60th and 65th anniversaries.

At a ceremony commemorating the 60th Anniversary of Social Security in 1995, Commissioner Chater, with the assistance of First Lady Hillary Clinton and Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, launched a series of public service announcements to educate the public about the value of Social Security benefits. The campaign, announced at a press conference in Washington, D.C. on August 14, 1995, was unveiled to coincide with the 60th anniversary of Social Security and focused on the real-life stories of two families. The announcements were part of a public information campaign to inform younger workers about the value of their Social Security taxes.

A Baltimore fire department inspector, his wife and son are living the American dream. Suddenly his family’s lives are shattered when his wife tragically dies while giving birth to their second child. A young admissions clerk at a trade school in Philadelphia is just beginning to get her feet on solid financial ground when a crippling spinal cord injury forces her to stop working.

Social Security was the common link. The fire inspector’s children received monthly survivor’s benefits because their mother worked and paid Social Security taxes. The former admissions clerk, with the help of her disability payments, went on to graduate school. to become a counselor to other people with disabilities.

The 65th Anniversary was recognized with a special program at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, N.Y., on August 5, 2000. On August 14, 2000, [23] Commissioner Apfel dedicated a 65th Anniversary Garden on the grounds of SSA headquarters in Baltimore. He described the Garden and its purpose:

“Today we are celebrating the 65th anniversary of the Social Security program. Many would agree that this program is the most successful domestic program in our nation’s history, as well as one of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s most important and lasting legacies. In many ways, it was his gift of hope to the American people during a very bleak period in our history. And the gift has endured.”

President Clinton, throughout his eight years in office, worked to strengthen Social Security. He spoke about the Social Security program often and said:

“it reflects some of our deepest values – the duties we owe to our parents, the duties we owe to each other when we’re differently situated in life, the duties we owe to our children and our grandchildren. Indeed, it reflects our determination to move forward across the generations and across the income divides in our country, as one America.” [24]

FOOTNOTES

[6] See the Independent Agency chapter for information about SSA’s Acting Commissioners and top leadership, including political appointees, during the Clinton Administration.

[7] See the Independent Agency chapter for specific information about major accomplishments during Commissioners Chater and Apfel’s tenure.

[8] The three 1991 goals were: (1) To serve the public with compassion, courtesy, consideration, efficiency and accuracy, (2) To protect and maintain the American people’s investment in the Social Security Trust Funds and to instill public confidence in Social Security programs, and (3) To create an environment that ensures a highly skilled, motivated workforce dedicated to meeting the challenge of SSA’s public service mission.

[12] For example, in February 1997, GAO designated the SSI program as a high-risk area, citing concerns in three programmatic areas: (1) financial eligibility, (2) continuing disability eligibility, and (3) return-to-work. Another GAO “high-risk” report issued in January 1999 on the SSI program cited the same areas.

[13] Management of the Supplemental Security Income Program: Today and in the Future, October, 1999.

[14] Social Security Administration: Effective Leadership Needed to Meet the Daunting Challenges, GAO/T-OGC-96-7, July 25, 1996.

[16] The 1995 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees, page 54; the 2000 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees, page 51.

[20] Social Security Administration: Update on Year 2000 and Other Key Information Technology Initiatives (GAO/T-AIMD-99-259, July 29, 1999).

[21] Interview with Social Security Assistant Deputy Commissioner for Systems Kathleen Adams, by the Government Computer News Magazine.

[22] John Winant, the Republican minority member of the Social Security Board resigned in order to be free to defend the Act.

[24] Remarks by the President on Social Security, Gaston Hall, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., February 9, 1998.

Exhibit 1: Chronology of SSA Events -- 1993-2000