Statement of Michael J. Astrue,

Commissioner,

Social Security Administration

before the Committee on Ways and Means

Subcommittee on Social Security

June 27, 2012

Chairman Johnson, Ranking Member Becerra, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for this opportunity to discuss our appeals process, which is one of the largest administrative adjudicative systems in the world. We are committed to continuing to improve this process for our disability claimants. Today, I will provide an overview of the appeals process, update you on our efforts to eliminate the hearings backlog, and discuss the President’s fiscal year (FY) 2013 funding request.

General Administrative Review Process

The Supreme Court has accurately described our administrative process as “unusually protective” of the claimant. 1 Indeed, we strive to ensure that we make the correct decision as early in the process as possible, so that a person who truly needs disability benefits receives them in a timely manner. In most cases, we decide claims for benefits using an administrative review process that consists of four levels: (1) initial determination; (2) reconsideration determination; (3) hearing; and (4) appeals.2 At each level, the decision-maker bases his or her decisions on provisions in the Social Security Act (the Act) and regulations.

In most States, a team consisting of a State disability examiner and a State agency medical or psychological consultant makes an initial determination at the first level. The Act requires this initial determination.3 A claimant who is dissatisfied with the initial determination may request reconsideration, which is performed by another State agency team.

A claimant who is dissatisfied with the reconsidered determination may request a hearing.4 The Act requires us to give a claimant “reasonable notice and opportunity for a hearing with respect to such decision.”5 Under our regulations, an administrative law judge (ALJ) conducts a de novo hearing unless the claimant waives the right to appear in person, or the ALJ can issue a fully favorable decision without a hearing; in these cases, the ALJ issues a decision based solely on the written record.6 If the claimant is dissatisfied with the ALJ’s decision, he or she may request Appeals Council (AC) review.7 The Act does not require administrative review of an ALJ’s decision. If the AC issues a decision, it becomes our final decision. If the AC decides not to review the ALJ’s decision, the ALJ’s decision becomes our final decision. A claimant may request judicial review of our final decision in Federal district court.8

The Administrative Appeals Process

Our administrative appeals process consists of three levels: reconsideration, hearing, and appeal. My testimony will focus primarily on the hearings and appeals process; however, I will first briefly describe the reconsideration level of review.

Reconsideration

The reconsideration stage is the first level of appeal in our disability claims process. A team consisting of a State agency disability examiner and a medical or psychological consultant, neither of whom were involved in making the initial determination, reviews the claimant’s case.9 If necessary, the team will request additional evidence or a new consultative examination.

The reconsideration determination is a thorough and independent examination of all evidence on record. The team is not bound by the determination made at the initial level.

If the claimant is dissatisfied with the reconsidered determination, the claimant has 60 days after the date he or she receives notice of the determination to request a hearing before an ALJ, unless we extend the deadline for good cause. A claimant may request an extension of time to file an appeal at every level of agency review and may request an extension of time to file a civil action in Federal court.

Hearings and Appeals Process

We have over 70 years of experience in administering the hearings and appeals process. Since the passage of the Social Security Amendments of 1939 (1939 Amendments), the Act has required us to hold hearings to determine the rights of individuals to old-age and survivors’ insurance benefits.

To hold the hearings required by the 1939 Amendments, we established the Office of the Appeals Council (OAC) in 1940. The OAC consisted of 12 “referees” and a Central Office staff.10 The referees, who heard cases and issued decisions, were located in each of the then-12 regional offices across the country.11 The Central Office consisted of a three-member AC and a consulting referee (whose role eventually developed into the Office of General Counsel). The Chairman of the AC also served as the head of the OAC. To promote uniformity and ensure correct decisions, the AC reviewed all referees’ decisions. The 1939 Amendments allowed claimants to appeal our final decisions to Federal court.

After establishing the OAC, we changed the name of that component several times. Since 2006, we have called it the Office of Disability Adjudication and Review (ODAR). ODAR manages the hearings and AC levels of the administrative review process.

Over the years, the numbers of ALJs and hearing offices rapidly grew as the Social Security program grew. Recently, we added staff to help us meet growing demand and allow us to focus our resources on those parts of the country that need our services most. In addition, we have expanded the use of video hearings, opened five national hearing centers, and realigned the service areas of some of our offices. However, the essential attributes of the hearings and appeals process have remained essentially the same since 1940. When it established the hearings and appeals process in 1940, the Social Security Board sought to balance the need for accuracy and fairness to the claimant with the need to handle a large volume of claims in an expeditious manner.12 Those twin goals still motivate us. As the Supreme Court has observed, the Social Security hearings system “must be fair – and it must work.”13

Hearing Level

When a hearing office receives a request for a hearing from a claimant, the hearing office staff prepares a case file, assigns the case to an ALJ and schedules a hearing. The ALJ decides the case de novo, meaning that he or she is not bound by the determinations made at the initial and reconsideration levels. The ALJ reviews any new medical and other evidence that was not available to prior adjudicators. The ALJ will also consider a claimant’s testimony and the testimony of medical and vocational experts called for the hearing. If a review of all of the evidence suggests that we can issue a decision that is fully favorable to the claimant without holding a hearing, an ALJ or attorney adjudicator may issue an on-the-record, fully favorable decision.14 If an on-the-record decision is not possible, an ALJ holds a hearing.

As I have testified before this subcommittee previously, the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) contains provisions that ensure qualified decisional independence for our ALJs and places certain limits on the performance management of our ALJs. For example, by law ALJs are exempt from performance appraisals and cannot receive awards based on performance.15 We support Congress’ intent to ensure the integrity of the hearings process.16 A key component of the integrity of our hearings process is that ALJs act as independent adjudicators — who fairly apply the standards in the Act and our regulations. We respect the qualified decisional independence that is integral to the ALJ’s role as an independent adjudicator. Indeed, the Supreme Court has recognized that Congress modeled the APA on our hearings process.

In contrast to Federal court proceedings, our ALJ hearings are non-adversarial. Formal rules of evidence do not apply, and the agency is not represented.17 At the hearing, the ALJ takes testimony under oath or affirmation. The claimant may elect to appear in-person at the hearing or consent to appear via video. The claimant may appoint a representative (either an attorney or non-attorney) who may submit evidence and arguments on the claimant’s behalf, make statements about facts and law, and call witnesses to testify. The ALJ may call vocational and medical experts to offer opinion evidence, and the claimant or the claimant’s representative may question these witnesses.

If, following the hearing, the ALJ believes that additional evidence is necessary, the ALJ may leave the record open and conduct additional post-hearing development; for example, the ALJ may order a consultative exam. Once the record is complete, the ALJ considers all of the evidence in the record and makes a decision. The ALJ decides the case based on a preponderance of the evidence in the administrative record. A claimant who is dissatisfied with the ALJ’s decision generally has 60 days after he or she receives the decision to ask the AC to review the decision.

Appeals Council

Upon receiving a request for review, the AC evaluates the ALJ’s decision, all of the evidence of record, including any new and material evidence that relates to the period on or before the date of the ALJ’s decision, and any arguments the claimant or his or her representative submits. The AC may grant review of the ALJ’s decision, or it may deny or dismiss a claimant’s request for review. The AC will grant review in a case if there appears to be an abuse of discretion by the ALJ; there is an error of law; the actions, findings, or conclusions of the ALJ are not supported by substantial evidence; or if there is a broad policy or procedural issue that may affect the general public interest.

If the AC grants a request for review, it may uphold part of the ALJ’s decision, reverse all or part of the ALJ’s decision, issue its own decision, remand the case to an ALJ, or dismiss the original hearing request. When it reviews a case, the AC considers all the evidence in the ALJ hearing record (as well as any new and material evidence), and when it issues its own decision, it bases the decision on a preponderance of the evidence.

If the claimant completes our administrative review process and is dissatisfied with our final decision, he or she may seek review of that final decision by filing a complaint in Federal district court. However, if the AC dismisses a claimant’s request for review, he or she cannot appeal that dismissal.

We also rely on the AC to improve the quality of our hearing decisions. In September 2010, we established the Division of Quality (DQ) within the AC, in order to expand our quality assurance role and to help maintain appropriate stewardship of the Trust Fund. Currently, DQ reviews a statistically valid sample of un-appealed favorable ALJ hearing decisions before those decisions are effectuated (i.e., finalized). In FY 2011, DQ reviewed 3,692 partially and fully favorable decisions issued by ALJs and attorney adjudicators, and took action on about 22 percent, or 812, of those cases.18

DQ also conducts focused reviews on specific hearing offices, ALJs, representatives, doctors, etc.19 ODAR identifies potential subjects for focused reviews from a variety of sources, including data collected through our systems, findings from pre-effectuation reviews, and internal and external referrals received from various sources regarding potential non-compliance with our regulations and policies. One way we use these reviews is to identify common errors in ALJ decisions. The results of these reviews show common errors to be failure to adequately develop the record, lack of supporting rationale, and improper evaluation of opinion evidence. Furthermore, we use the comprehensive data and analysis provided by DQ to provide feedback to other components on policy guidance and litigation issues.

Federal Level

If the AC makes a decision, it is our final decision. If the AC denies the claimant’s request for review of the ALJ’s decision, the ALJ’s decision becomes our final decision. A claimant who wishes to appeal an AC decision or an AC denial of a request for review has 60 days after receipt of notice of the AC’s action to file a complaint in Federal District Court.

In contrast to the ALJ hearing, Federal courts employ an adversarial process. In District Court, an attorney usually represents the claimant and attorneys from the United States Attorney’s office or our Office of the General Counsel represent the Government. When we file our answer to that complaint, we also file with the court a certified copy of the administrative record developed during our adjudication of the claim for benefits.

The Federal District Court considers two broad inquiries when reviewing one of our decisions:

whether we correctly followed the Act and our regulations, and whether our decision is

supported by substantial evidence of record. On the first inquiry – whether we have applied the

correct law – the court typically will consider issues such as whether the ALJ applied the correct

legal standard for evaluating the issues in the claim, such as the credibility of the claimant’s

testimony or the treating physician’s opinion, and whether we followed the correct procedures.

On the second inquiry, the court will consider whether the factual evidence developed during the administrative proceedings supports our decision. The court does not review our findings of fact de novo, but rather, considers whether those findings are supported by substantial evidence. The Act prescribes the “substantial evidence” standard, which provides that, on judicial review of our decisions, our findings “as to any fact, if supported by substantial evidence, shall be conclusive.” The Supreme Court has defined substantial evidence as “such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion.”20 The reviewing court will consider evidence that supports the ALJ’s findings as well as evidence that detracts from the ALJ's decision. However, if the court finds there is conflicting evidence that could allow reasonable minds to differ as to the claimant’s disability, and the ALJ’s findings are reasonable interpretations of the evidence, the court must affirm the ALJ's findings of fact.

If, after reviewing the record as a whole, the court concludes that substantial evidence supports the ALJ’s findings of fact and the ALJ applied the correct legal standards, the court will affirm our final decision. If the court finds either that we failed to follow the correct legal standards or that our findings of fact are not supported by substantial evidence, the court typically remands the case to us for further administrative proceedings, or in rare instances, reverses our final decision and finds the claimant eligible for benefits.

History of Hearing Workloads and Initiatives

We have made great strides in reducing the hearings backlog in recent years. To provide some context, I will sketch the history of our hearing workload and our prior attempts to manage its increases.

Hearing Workloads

When we established the hearings process in 1940, we designed it to handle a larger number of cases, relative to other hearing processes.21 However, hearings originally constituted a small workload compared to today’s numbers. In FY 2007, we received nearly 580,000 hearing requests; last fiscal year, we received over 859,000 hearing requests, which was a record number.

Legislative activity is one of the catalysts for this growth. Over time, Congress expanded the scope and reach of the Act, and these legislative changes resulted in increasing dockets. For example, the Social Security Amendments of 1954 created the first operational Social Security disability program; it instituted the disability freeze for workers who met the law’s definition of disability.22 Due to this legislation, hearing requests increased from approximately 3,800 in 1955 to 8,000 in 1956. After the implementation of the Social Security Amendments of 1972, which created the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, and the Black Lung Benefits Act of 1972, hearing requests more than doubled from FY 1973 to 1975.23

As our workloads drove pending levels and processing times up, the courts took notice. In the 1970s, several Federal District Courts entered judgments in statewide class actions requiring us to hear cases in their States within specific timeframes.

Previous Initiatives

Over the years, we tried to find ways to meet the demand for hearings. For example, in 1975 we started our first decision-writing program. Under this program, staff attorneys wrote the ALJ decisions based on instructions they received from the judges.24 By lessening the decisionwriting burden for our ALJs, we enabled them to issue more decisions. While this change took hold, other well-intentioned initiatives have fallen short.

Disability Process Reengineering

In 1993, the agency established a task force to reengineer the disability claims process. The task force devised a plan “to dramatically improve the disability claim process,” and the agency released this plan in September 1994. 25 As a part of this redesign, the plan contemplated two changes to the hearings and appeals level. First, the plan created a new position, the adjudication officer (AO). The AO would explain the hearings process to the claimant, conduct personal conferences, prepare claims, and schedule hearings. Moreover, the AO could allow the claim at any point prior to the hearing if sufficient evidence supported a favorable decision. The plan would also allow claimants unsatisfied with their hearing decisions to appeal them directly to Federal district court, rather than requesting AC review.

The plan included 83 initiatives. Interested parties criticized the scope and complexity of these initiatives. For example, in September 1996 the Government Accountability Office testified before this subcommittee that the number of complex initiatives would likely delay the plan’s completion, and that the agency should focus its efforts on fewer initiatives.26 Consequently, the agency never fully implemented this plan.

Hearings Process Improvement (HPI)

In March 1999, the agency released a plan to improve the agency’s management of the disability program. As a part of this plan, in June 1999 the agency implemented HPI. This initiative sought to improve hearing process efficiency by addressing the following problems: 1) the high number of hearing office staff involved in preparing a case for a hearing; 2) the “stove pipe” nature of employees’ job duties; and 3) inadequate management information necessary to monitor and track each case through the process. HPI sought to create a process that fully prepared the cases for adjudication by first determining the necessary actions early in the process and ensuring that case development or expedited review occurred. A few of the changes HPI made to hearing office organization, such as creating the position of hearing office director, are still in place today. However, Congress would not fund HPI as originally conceived, and in its truncated form it failed to increase the efficiency of our hearing process to the extent envisioned.

Disability Service Improvement (DSI)

In August 2006, the agency began the roll out of DSI. This initiative sought to streamline the entire disability claims process and ensure that the agency made the right decision as early in the process as possible. At the hearing level, the record would close after an ALJ decision, and the Decision Review Board would gradually replace the AC. DSI also created a new position, the Federal Reviewing Official (FedRO), to review State agency determinations upon the request of the claimant; this level would replace the reconsideration level of review. The Quick Disability Determination initiative, which we use today, originated under DSI. However, the administrative costs of other features of DSI, such as the FedRO, were more than expected. Moreover, the staffing requirements under DSI had very little connection to reducing the hearings backlog.

Hearings Backlog Reduction Plan

Despite these well-intentioned efforts, the disability backlogs continued to rise. During my first week as Commissioner in February 2007, I testified before this Subcommittee about the hearings backlog. To put it mildly, you were extremely upset about the hardships your constituents faced while waiting for a disability decision. The backlogs had steadily risen, and the plan I inherited to fix those backlogs, DSI, was draining precious resources and making the problem worse. The numbers tell the story. At the time, over 63,000 people waited over 1,000 days for a hearing, and some people waited as long as 1,400 days. We were failing the public. Rather than devise yet another signature initiative that would not stand the test of time, we went back to the basics.

We developed an operational plan that focused on the gritty work of truly managing the unprecedented hearings workload. We made dozens of incremental changes, including using video more widely, improving IT, simplifying regulations, standardizing business processes, and establishing ALJ productivity expectations, to name just a few. Importantly, with your support, we also committed the resources employees needed to get this work done.

We have hired additional ALJs for the offices with the heaviest workloads. We expanded the Senior Attorney Adjudicator program, which gives adjudicators the authority to issue fully favorable on-the-record decisions in order to conserve ALJ resources for the more complex cases and cases that require a hearing.

We opened five National Hearing Centers (NHCs) to further reduce hearings backlogs by increasing adjudicatory capacity and efficiency with a focus on a streamlined electronic business process. Transfer of workload from heavily backlogged hearing offices is possible with electronic files, thus allowing the NHC to target assistance to these areas of the country. We implemented the Representative Video Project (RVP) to allow representatives to conduct hearings from their own office space with agency-approved video conferencing equipment. 27

In 2010 and 2011, we opened 24 new hearing offices and satellite offices. While a lack of funding forced us to cancel plans for additional offices, those we did open are making a substantial difference in communities that were experiencing the longest waits for hearings.

We increased usage of the Findings Integrated Templates (FIT) that improves the legal sufficiency of hearing decisions, conserves resources, and reduces average processing time. We introduced a standard Electronic Hearing Office Process, also known as the Electronic Business Process, to promote consistency in case processing across all hearing offices. We also built the “How MI Doing” tool that allows ALJs and support staff to view a graphical presentation of their up-to-date individual productivity as compared to others in their office, their region, and the Nation.

We expanded automation tools to improve speed, efficiency, quality, and accountability. We initiated the Electronic Records Express project, which provides electronic options for submitting health and school records related to disability claims. This initiative saves critical administrative resources because our employees burn fewer CDs freeing them to do other work. In addition, appointed representatives with e-Folder access have self-service access to hearing scheduling information and the current Case Processing and Management System (CPMS) claim status for their clients, reducing the need for them to contact our offices. We have registered over 9,000 representatives for direct access to the electronic folder. We also implemented Automated Noticing that allows CPMS to automatically produce appropriate notices based on stored data. We implemented centralized printing and mailing that provides high speed, high volume printing for all ODAR offices. We implemented Electronic Signature that allows ALJs and Attorney Adjudicators to sign decisions electronically.

We have Federal disability units that provide extra processing capacity throughout the country. In recent years, these units have been assisting stressed State disability determination agencies. After evaluating our limited resources, our success in holding down the initial disability claims pending level, and a further spike in hearings requests, we redirected these units in February 2012 to assist in screening hearings requests. Our Federal disability units can make fully favorable allowances, if appropriate, without the need for a hearing before an ALJ.

We also listened to criticism from you and others. We have tried to make the right decision upfront as quickly as possible. For instance, we are successfully using our Compassionate Allowance and Quick Disability Determination initiatives to fast-track disability determinations at the initial claims level for over 150,000 disability claimants each year, while maintaining a very high accuracy rate. Currently about 6 percent of initial disability claims qualify for our fasttrack processes, and we expect to increase that number as we add new condition to our Compassionate Allowance program. This helps keep these cases out of our appeals process altogether.

Results

This plan has worked. Average processing time, which stood at 532 days in August 2008, steadily declined for more than three years, reaching its lowest point of 340 days in October 2011.

I want to talk about measuring the hearings backlog. In 2007, filing rates had been stable for some time, so looking at the number of pending cases was a reasonable, if imperfect method to measure progress.

As the recession hit and the number of requests for a hearing dramatically increased, we steadily improved our performance when measured by average processing time, the best metric for tracking progress, particularly in times when filings are changing rapidly. When people request a hearing, they want to know how long it will take to get a decision. Much like a line in a store, the customer’s experience depends not on how many other people are waiting, but on how quickly we help them. Nobody wants to get bumped and jostled; nobody wants to stand in a line that does not move; and everyone becomes frustrated when there are not enough cashiers to handle the customers. With grocery stores, we can choose where we get our groceries and decide if we are willing to accept a particular store’s customer service, but Americans seeking Social Security benefits have only one place to go. With your help, we are working to make their experience fair, accurate, and timely.

The most important metric for claimants is how long they will have to wait for a hearing decision; consequently, our primary goal is now average processing time, which is the average number of days it takes to get a hearing decision (from the date of the hearing request). In August 2008, people waited an average of 532 days. Today they are waiting only 350 days.

Average processing times also became more uniform across the country. The most dramatic improvements have occurred in the most backlogged offices. To provide concrete examples, average processing time in Atlanta North dropped from 900 days to 351 days in May 2012. Oak Park, Michigan improved from 764 days to 254 days. Columbus, Ohio went from 881 days to 351 days. Currently, no office has an average processing time greater than 475 days. Fifteen offices have hit our goal of 270 days or less, and many others are getting close. While our goal is to reach an average processing time of 270 days by the end of next fiscal year, that number depends on our ability to timely hire judges and support staff.

These numbers are even more impressive because we have given priority to the oldest cases, which are generally the most complex and time-consuming. Five years ago, we defined an aged case as one waiting over 1,000 days for a decision. At that time, 63,000 people waited over 1,000 days for a hearing, and some people waited as long as 1,400 days, which is a moral outrage. Since 2007, we have decided over 600,000 of the oldest cases. Each year we lower the threshold for aged cases to ensure that we continue to eliminate the oldest cases first. We ended FY 2011 with virtually no cases over 775 days old. Through the steady efforts of our employees, we now define an aged case as one that is 725 days or older, and we have already completed over 90 percent of them. Next year, our management goal is to raise the bar on ourselves again by focusing on completing all cases over 675 days old.

This emphasis on eliminating aged cases increases average processing times, so we also look ahead to see how long people in the queue have been waiting for a hearing. At the beginning of FY 2007, the number was 324 days. That number today is just 208 days, a 36 percent decrease, and we are hopeful that figure will drop again next year. Also, at the beginning of FY 2007, nearly 40 percent of pending hearing requests were older than one year. We reduced this figure to 14 percent at the end of May 2012.

To reduce the hearings backlog, we set an expectation that our ALJs should decide between 500 and 700 cases annually.28 When we established that productivity expectation in late 2007, only 47 percent of the ALJs were achieving it. By the end of May 2012, 72 percent met the expectation, and we expect that percentage to continue to rise throughout this fiscal year. I thank them for their hard work.

This improvement in productivity has helped us make progress despite the significant increase in requests for hearings. In FY 2011, we received over 859,000 hearing requests, which is about a 19 percent increase from what we received in FY 2010.

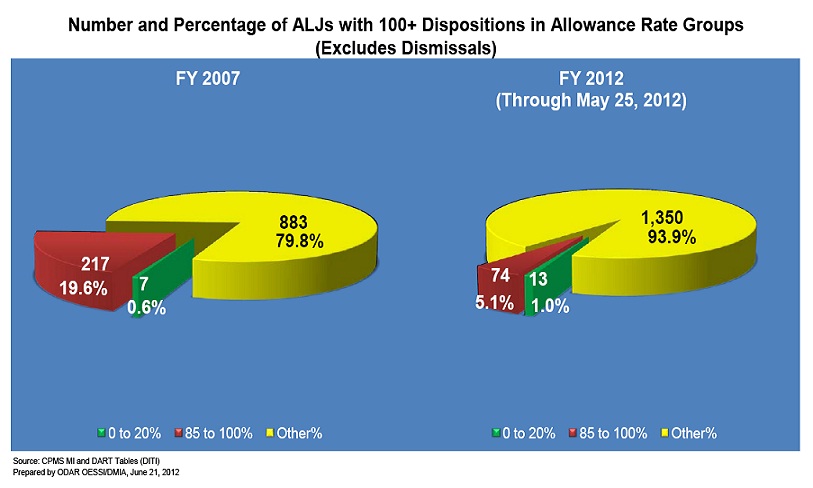

Our ALJs are not meeting our productivity goals by “paying down the backlog,” as has sometimes been alleged. Instead, over this time period, outcomes across ALJs have become more standardized, reflecting an emphasis on quality decision making. There are now significantly fewer judges who allow more than 85 percent of their cases than there were in FY 2007 (see the chart at the end of my testimony).

We have created new tools to focus on quality. Each quarter we train our adjudicators on the most complex, error-prone provisions of law and regulation. We provide feedback on decisional quality, giving adjudicators access to their remand data. We also make available specific training to address individualized training needs.

Moreover, since we are handling more hearings, the number of new Federal court cases filed challenging our denials has gone up. In FY 2007, dissatisfied claimants filed 11,951 new cases. That number rose to 14,236 in FY 2011, and we project that there will be about 19,100 new cases filed in FY 2013. Although the actual number of civil actions increased, the ratio of civil actions filed versus our denials has declined. Our success in the courts has also improved. In FY 2011, courts affirmed our decisions in 51 percent of the cases decided, up from 49 percent in FY 2007, and court reversals have decreased from 5 percent to under 3 percent of cases over this time.

President’s FY 2013 Budget Request

I am concerned that despite our employees’ hard work, we will begin to move drastically backwards on most of our key service goals. In fiscal years 2011 and 2012, the difference between the President’s Budget and our appropriation was greater than in any other year of the previous two decades. Also, last year Congress rescinded $275 million from our IT carryover funding, which will damage our efforts to maintain our productivity increases through IT innovation.

We are starting to see the consequences of these decisions. Not letting you know the consequences of Congress’ decision would be a disservice to you, the American people, and the agency. Despite our employees’ hard work, the progress in addressing our hearings backlog is happening more slowly than the public deserves. It has slowed in the last year, and we lost our margin for error when, for budgetary reasons, we cancelled our plans to open eight new hearing offices in Alabama, California, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New York, and Texas.29

We are doing what we can to compensate. We are hiring additional ALJs, albeit fewer than we had planned, and using our reemployed annuitant authority to bring back experienced judges who have recently retired. We are maintaining a high support staff-to-ALJ ratio to ensure cases are ready to hear, and we are allowing the hearing offices to work overtime to try to keep up with the surge in hearings.

We need your support and we need a timely and adequate supply of well-qualified judicial candidates from the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). If we are not appropriately funded and we cannot timely hire enough qualified ALJs and support staff, our progress will erode. We also need our projections for the number of initial claims and hearing requests to be on target if we are to achieve our goal of an average processing time of 270 days by the end of next year.

I urge Congress to support the President’s request because we have proven that we deliver when we are properly resourced. Through the hard work of our employees and technological advancements, we have increased employee productivity by an average of about four percent in each of the last five years, a remarkable achievement that very few organizations—public or private—can match.

Conclusion

Congress made eliminating the hearings backlog our top priority. If you told me in 2007 that we would have to contend with budget cuts for two straight years and the most severe economic downturn since the Great Depression, I would have said that it would be impossible to eliminate the backlog. The fact that we are still in a position to realize this goal is a testament to our employees’ dedication and skill. Amid huge economic and budgetary unpredictability, we have stayed focused on eliminating the causes of your moral outrage in 2007. Now we need Congress to enact the President’s Budget request so that we can meet our important commitments to the American people.

________________________________________________

1 Heckler v. Day, 467 U.S. 104 (1984).

2 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.900, 416.1400. My testimony focuses on disability determinations, but the review process

generally applies to any appealable issue under the Social Security programs.

3 Sections 205(b) and 1631(c)(1)(A) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(b), 1383(c)(1)(A).

4 For disability claims, 10 States participate in a “prototype” test under 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.906, 416.1406. In these

States, we eliminated the reconsideration step of the administrative review process. Claimants who are dissatisfied

with the initial determinations on their disability cases may request a hearing before an ALJ. The 10 States

participating in the prototype test are Alabama, Alaska, California (Los Angeles North and West Branches),

Colorado, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, and Pennsylvania.

5 Sections 205(b)(1), 1631(c)(1)(A) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(b)(1), 1383(c)(1)(A). A claimant has 60 days after

the date he or she receives notice of the determination to request a hearing before an ALJ.

6 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.929, 416.1429.

7 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.967-404.968, 416.1467-416.1468.

8 Sections 205(g), 1631(c)(3) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(g), 1383(c)(3).

9 A disability beneficiary who is appealing an initial-level determination that his or her impairment has medically

ceased may request a disability hearing before a disability hearing officer at the reconsideration level.

10 In August 1959, we changed the title of referee to “hearing examiner.” In 1972, the Civil Service Commission

changed this title to “Administrative Law Judge.”

11 We have increased our adjudicatory capacity to address rising workloads. By 1957, we had 75 referees. In 1973,

our ALJ corps exceeded 500 judges for the first time. Currently, there are 1,472 judges in our ALJ corps

12 Basic Provisions Adopted by the Social Security Board for the Hearing and Review of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Claims, at 4-5 (January 1940).

13 Richardson v. Perales, 402 U.S. 389, 399 (1971).

14 Under the Attorney Adjudicator program, our most experienced attorneys spend a portion of their time making

on-the-record, disability decisions in cases where enough evidence exists to issue a fully favorable decision without

waiting for a hearing. 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.942, 416.1442.

15 5 U.S.C. §4301. Although the APA prevents us from rating the performance of our ALJs, it does not preclude us

from setting expectations for them. As the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has observed, “The setting of

reasonable production goals, as opposed to fixed quotas, is not in itself a violation of the APA….[I]n view of the

significant backlog of cases, it was not unreasonable to expect ALJs to perform at minimally acceptable levels of

efficiency. Simple fairness to claimants awaiting benefits required no less.” Nash v. Bowen, 869 F.2d 675, 680-681

(2d. Cir.), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 812 (1990). We currently set an expectation of 500 to 700 dispositions every year,

or 42 to 58 dispositions a month.

16 To ensure the integrity of the hearings process, we assign cases to ALJs in rotation. This procedure promotes

fairness and reduces manipulation of judicial assignment.

Along these lines, we now withhold the name of the ALJ assigned to a hearing. We have experienced some

opposition to this practice. In Lucero v. Astrue, No. 12-cv-274-JB-LFG (D. N.M.), plaintiffs sought mandamus and

injunctive relief that would have barred us from withholding the names of the ALJs assigned to the plaintiffs’ cases.

On May 4, 2012, the plaintiffs voluntarily withdrew their motion for a preliminary injunction. The district court

entered a final judgment dismissing, without prejudice, all of plaintiffs’ claims against us on May 18.

In its report accompanying the FY 2013 Labor-HHS appropriation bill, the Senate Appropriations Committee

expressed its concern that our practice could have unintended consequences. The committee directed the agency to

submit a report by November 1, 2012 on this issue. However, the committee also noted that attempts by claimant

representatives to manipulate the hearing process to find favorable judges challenge the integrity of our process, and

supported our goal of reducing this manipulation.

17 During the 1980s, we tried to pilot an agency representative position at select hearing offices. However, a United

States District Court held that the pilot violated the Act, intruded on ALJ independence, was contrary to

congressional intent that the process be “fundamentally fair,” and failed the constitutional requirements of due

process. Salling v. Bowen, 641 F. Supp. 1046 (W.D. Va. 1986). We subsequently discontinued the pilot due to the

testing interruptions caused by the Salling injunction and general fiscal constraints.

Congress originally supported the project; however, we experienced significant congressional opposition once the

pilot began. For example, members of Congress introduced legislation to prohibit the adversarial involvement of

any government representative in Social Security hearings, and 12 Members of Congress joined an amicus brief in

the Salling case opposing the project.

18 In those instances, the AC either remanded the case to the hearing office for further development or issued a

decision that modified the hearing decision.

19 Since these focused reviews are post-effectuation reviews, they do not change case outcomes.

20 Consolidated Edison Co. of New York v. N.L.R.B., 305 U.S. 197 (1938).

21 Basic Provisions Adopted by the Social Security Board for the Hearing and Review of Old-Age and Survivors

Insurance Claims, at 4 (January 1940).

22 We compute retirement benefits based on earnings; therefore, a disabled worker with a period of disability could

have experienced reduced or no retirement benefits due to his or her lost earnings. The 1954 amendments

established the disability freeze, under which we could exclude a disabled worker’s periods of disability when

calculating his or her retirement benefits.

23 For a brief period in the 1970s, the SSI hearing examiners hired to handle SSI cases could hear only SSI cases; the

ALJs hired to handle Black Lung cases could hear only Black Lung cases; and the ALJs hired to hear disability

insurance (DI) cases could hear only DI cases. The lack of an integrated ALJ corps denied flexibility that could

have helped with the increasing workloads more efficiently.

24 Currently, both attorneys and non-attorney specialists may write these decisions.

25 59 Fed. Reg. 47887 (September 19, 1994).

26 Testimony before the House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Social Security, September 12, 1996.

27 Unfortunately, only a small number of representatives have participated in the RVP. Increased participation,

which may be happening as the cost of the equipment declines, would make our process much more efficient and

allow us to save money on office space.

28 In addition, we limit the limit the number of cases assigned per year to an ALJ.

29 We have also closed most of our remote hearing sites.