Deputy Commissioner for Disability Adjudication and Review

Social Security Administration

before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform

Subcommittee on Energy Policy, Health Care and Entitlements

June 27, 2013

Chairman Lankford, Ranking Member Speier, and Members of the Subcommittee:

Thank you for this opportunity to discuss our hearing process. Today, I will talk about our recent public service improvements, explain the way we manage our administrative law judges (ALJ), describe the disability evaluation process, and describe the hearings and appeals process.

Introduction

At the Social Security Administration (SSA), we do everything within our power to meet the public’s expectation of exceptional stewardship of program dollars and administrative resources. We strive to preserve the public’s trust in our program and ensure that the correct benefits go toward assisting only the appropriate people.1

Our administrative review process for deciding claims for benefits consists of four levels: (1) initial determination; (2) reconsideration determination; (3) hearing before an ALJ; and (4) review by the Appeals Council (AC). At each level, the decision-maker bases his or her decisions on provisions in the Act and regulations. My testimony focuses on the hearings and appeals process (levels 3 and 4). 2

Improving Public Service and Oversight

I would like to provide some context about our recent improvements to the appeals process.

Improving Public Service

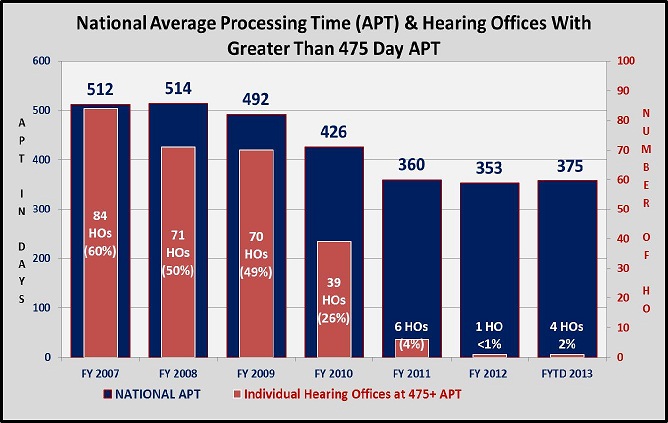

In fiscal year (FY) 2007, the average wait for a hearing decision was over 500 days, and over 63,000 people waited over 1,000 days for a decision. Some people even waited as long as 1,400 days.

In developing efficient and effective solutions to the hearing backlogs and delays, we implemented a comprehensive operational plan to better manage our unprecedented workload. We made dozens of significant changes, including expanding video conferencing to conduct hearings, improving information technology, simplifying regulations, and standardizing business processes, to name just a few. Congress provided additional resources, which were critical to supporting our improvements.

Today, the results are clear-our plan has worked exceptionally well. We have significantly improved the timeliness and quality of our hearing decisions. We steadily reduced the wait for a hearing decision from a high of 512 days in FY 2007, to 375 days in FY 2013.

Figure 1: National Average Processing Time (APT) & Hearing Offices (HO) with Greater Than 475 Days APT

We have made tremendous improvement in our service to the public by focusing on our most aged cases.3 We have decided nearly a million aged cases since FY 2007, and today we have virtually no hearing requests over 700 days old, with the vast majority of our cases falling between 100 to 400 days old. The most dramatic improvements have occurred in the most backlogged offices.

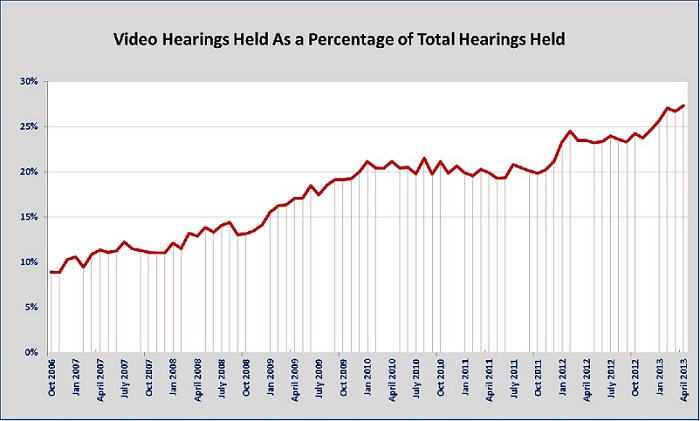

Our improvements include modernizing our information technology infrastructure in the hearing operation. We successfully implemented an electronic record system that gives us more flexibility in managing our workloads. We currently hold over 25 percent of our hearings using state-of-the-art video conferencing equipment; in October 2006, we used this equipment for less than ten percent of our hearings. Not only do we work in a fully electronic processing environment, but many claimants and third parties interact with us electronically as well.

Figure 2: Video Hearings Held As a Percentage of Total Hearings Held

Improved technology has helped us balance our work across hearing offices. In FY 2007, some hearing offices’ and regions’ backlogs were exceptionally high. Since FY 2007, we have opened five national hearing centers which use video technology to hold hearings to assist the most backlogged offices. We also created a national case assistance center to help offices prepare cases for a hearing. These national resources along with our realignment initiatives have helped us balance our work so that no hearing office faces excessive delays (see Figure 1). We continue to monitor workload trends closely so that we can quickly redirect resources as necessary to prevent micro-backlogs from forming in local areas. In addition to making us more efficient, we use this technology to collect and analyze trends, develop training, and clarify policy to improve the consistency and quality of our appeals process.

We have improved the training we provide to our ALJs to help ensure that our hearings and decisions are consistent with the law, regulations, rulings, and agency policy. Since FY 2007, our new ALJs have undergone rigorous selection and have participated in a two-week orientation, four-week in-person training, formal mentoring, and supplemental in-person training. We provide ALJs with easy access to information on the reasons for their AC remands and other data through an electronic tool. Because we can now gather and analyze common adjudication errors, we provide quarterly continuing education training to all adjudicators that targets these common errors. In addition, we have continued our training program that provides in-person technical training for 350 of our ALJs each year.

Our plan to improve service has allowed us to reduce our hearings backlog and increase the efficiency of our organization, while improving the quality of our decisions. The AC is remanding fewer cases to our ALJs for re-review, and the percentage of Federal court review requests is declining.

We could not have realized these improvements without the dedication of our ALJ corps and all of our employees. I thank them for their hard work.

Despite the tremendous advancement we have made, I am concerned that our improvements will erode. The number of hearing requests we receive each year remains high, and we are losing many ALJs and support staff, whom we are unable to replace. We are doing what we can to hold steady on our progress despite the loss of employees. However, our progress has slowed in the last year, and we were unable to open eight new hearing offices planned for Alabama, California, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, New York, and Texas.

I will now briefly discuss the steps we take to ensure ALJs issue timely and legally sufficient hearings and decisions, and to address ALJ personnel issues.

ALJ Management Oversight

ALJs have qualified decisional independence.4 That qualified decisional independence allows ALJs to issue decisions consistent with the law and agency policy, rather than decisions influenced by pressure to reach a particular result. The primary purpose of an ALJ’s qualified decisional independence is to enhance public confidence in the essential fairness of an agency’s adjudicatory process. We support Congress’ intent to ensure the integrity of the hearings process, and we note that the Supreme Court has recognized that Congress modeled the Administrative Procedure Act after our hearings process.

The mission of our hearing operation is to provide timely and legally sufficient hearings and decisions. For our hearing process to operate efficiently and effectively, we need ALJs to treat members of the public and staff with dignity and respect, to be proficient at working electronically, and to be able to handle a high-volume workload in order to make swift and sound decisions in a non-adversarial adjudication setting. Let me emphasize that the vast majority of the ALJs hearing Social Security appeals do an admirable job. They handle the complex cases in a timely manner, while conforming to the highest standards of conduct and quality.

However, when ALJ performance or conduct issues arise, agencies such as SSA are more limited in the manner in which they can attempt to correct the issues. Federal law precludes management from using some of the basic tools applicable to the vast majority of Federal employees. For example, agency managers may take certain corrective measures, such as informal counseling or issuing a disciplinary reprimand, to address ALJ underperformance or misconduct. However, the agency cannot take stronger disciplinary measures against an ALJ, such as removal or suspension, reduction in grade or pay, or furlough for 30 days or less, unless another agency-the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB)-finds that good cause exists.5

Historically, an ALJ’s qualified decisional independence has been misunderstood; qualified decisional independence does not empower ALJs to disregard the applicable law, regulation, or agency policy. The law is clear that, on matters of law and policy, our ALJs are required to comply with the agency’s interpretations. Since FY 2007, we have been working diligently to improve management oversight of our ALJs to ensure that they adhere to policies, regulations, and laws, while maintaining the ALJs’ qualified decisional independence. Simultaneously, we have pursued a much more proactive track to address conduct and performance issues of all employees, including ALJs. In many instances, we accomplished a great deal by simply communicating our expectations.

Ensuring Legally Sufficient Decisions

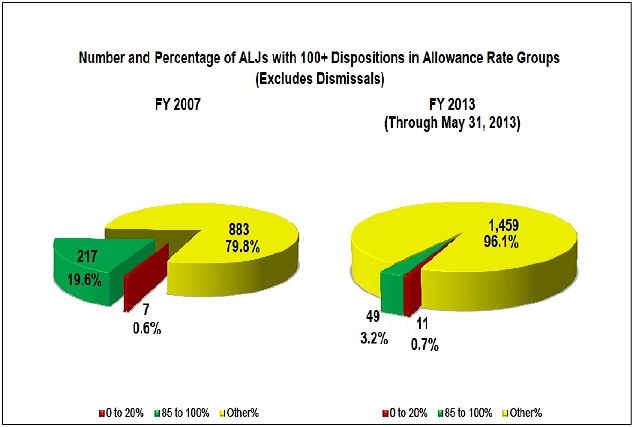

Our ALJs are not “paying down the backlog,” as has sometimes been alleged. These reports ignore the reality that we are making quicker, higher quality disability decisions. Over the past 6 years, the allowance and denial rates have become more consistent throughout the ALJ corps, reflecting an emphasis on quality decision making. There are now significantly fewer ALJs who allow more than 85 percent of their cases than there were in FY 2007. Meanwhile, there is less than one percent of the ALJ corps that pays fewer than 20 percent of their cases.

Figure 3: ALJ Allowance Rate Groups

Some observers have raised concerns about the variations in ALJ allowance rates. The agency expects some variation because of a variety of factors, such as Congressionally-required case rotation, geographical differences, and qualified decisional independence. I would like to note that the majority of ALJs cluster within a narrow range of the mean. Whether an ALJ falls within or outside of the mean, our focus is on the timeliness and legal sufficiency of his or her decisions.

The quality of our benefit decisions is a paramount concern for the agency. We took aggressive steps to institute a more balanced quality review in the hearings process. Our first effort in this area was to develop serious data collection and management information for the Office of Disability Adjudication and Review (ODAR). We then revived development of an electronic policy-compliance system for the AC. Because the Office of Appellate Operations (OAO) handles the final level of administrative review, it has a unique vantage point to give feedback to decision and policy makers. OAO developed a technological approach to harness the wealth of information the AC collects, turning it into actionable data. These new tools permitted the OAO to capture a significant amount of structured data concerning the application of agency policy in hearing decisions.

Using these data, we provide feedback on decisional quality, giving adjudicators real-time access to their remand data. We are creating better tools to provide individual feedback for our adjudicators. One such feedback tool is “How MI Doing?” This resource not only gives ALJs information about their AC remands, including the reasons for remand, but also information on their performance in relation to other ALJs in their office, their region, and the nation. Currently, we are developing training modules related to each of the 170 identified reasons for remand that we will link to the “How MI Doing?” tool. ALJs will be able to receive immediate training at their desks that is targeted to the specific reasons for the remand. We develop and deliver specific training that focuses on the most error-prone issues that our judges must address in their decisions. Data driven feedback informs business process changes that reduce inconsistencies and inefficiencies, and simplify rules.

In FY 2010, OAO created the Division of Quality (DQ) to focus specifically on improving the quality of our disability process. While AC remands provide a quality measure on ALJ denials, prior to the creation of DQ, we did not have the resources to look at ALJ allowances. Since FY 2011, DQ has been conducting pre-effectuation reviews on a random sample of ALJ allowances. Federal regulations require that pre-effectuation reviews of ALJ decisions must be selected at random or, if selective sampling is used, may not be based on the identity of any specific adjudicator or hearing office. Currently, DQ reviews a statistically valid sample of un-appealed favorable ALJ hearing decisions.

DQ also performs post-effectuation focused reviews looking at specific issues. Subjects of a focused review may be hearing offices, ALJs, representatives, doctors, and other participants in the hearing process. The same regulatory requirements regarding random and selective sampling do not apply to post-effectuation focused reviews. Because these reviews occur after the 60-day period a claimant has to appeal the ALJ decision, they do not result in a change to the decision.

These new quality initiatives have given us a new opportunity to improve our policy guidance. The data collected from these quality initiatives identify for us the most error-prone provisions of law and regulation, and we use this information to design and implement our ALJ training efforts. To ensure that all of our ALJs comply with law, regulations, and policies, we provide considerable training including both new and supplemental ALJ training. We train our ALJs on the agency’s rules and policies, and that training is vetted thoroughly by various components, including the component that is responsible for disability policy. For the past several years, our new ALJ training also has included a session that explains the scope and limits of an ALJ’s authority in the hearing process, including the ALJ’s obligation to follow the agency’s rules and policies. We also have implemented the ALJ Mentor Program, which pairs a new ALJ with an experienced ALJ, who provides advice, coaching, and expertise. Additionally, we provide regular guidance to ALJs through Chief Judge memoranda and bulletins, Interactive Video Teletraining sessions, and in responses to specific queries from the field.

Additional efforts to promote policy compliance include a pilot of the Electronic Bench Book (eBB) for our adjudicators. The eBB is a policy-compliant web-based tool that aids in documenting, analyzing, and adjudicating a disability case in accordance with our regulations. We designed this electronic tool to improve accuracy and consistency in the disability evaluation process.

These efforts are testing some longstanding traditions within ODAR. We are moving from training based primarily on anecdotal information as to our most significant problems to a data-driven identification of training, guidance, and policy gaps. We now develop training materials and automated tools designed to improve both the adjudicator’s efficiency and accuracy in case adjudication. We are transparent with the information that we are collecting so that the ALJs can more readily make use of the information.

Ensuring Timely Decisions

We are concerned with timeliness as well as quality. As one court noted, “Simple fairness to claimants awaiting benefits require[s] no less.”6

I spoke earlier about some of the initiatives the agency has employed to address the backlog since FY2007. Another one of those initiatives involved articulating a disposition goal for the ALJs. Specifically, we informed the entire ALJ corps of our expectation that they should issue between 500 and 700 legally sufficient dispositions annually. Our previous Chief ALJ established this expectation after consulting with a number of managers and ALJs about the reasonableness of the expectation. The goal of 500 to 700 dispositions was consistent with a prior goal set in 1981. At that time, the agency asked ALJs to complete 45 dispositions a month, or 540 a year. With significant advances in technology over the last 26 years, it was not surprising that when the agency articulated the 500-700 expectation, almost 50 percent of ALJs were issuing at least 500 dispositions a year. From the start, the 500 to 700 expectation was a goalit is not a quota; it is not a mandate. However, it has been a useful tool for individual ALJs to manage their dockets and improve their timeliness. For example, in FY 2012, approximately 78 percent of our ALJs met the expectation.

I want to be very clear that our agency expects that all dispositions will be legally sufficient, and we are demonstrating that we are serious about quality with our investments.

Moreover, in a survey conducted last year by the Association of Administrative Law Judges, nearly three out of four respondents found it “not difficult at all” or only “somewhat difficult” to meet the expectation. When given an opportunity to explain why they had not met the agency’s expectation, many respondents cited their status as new ALJs. We account for the learning curve for new ALJs. We reiterate the importance of making the right decision; consequently, we do not ask our newly-hired ALJs to meet the full workload expectation during the first year on the job.

When workflow issues arise that may affect an ALJ’s performance, the agency works with the ALJ on an informal basis to determine whether there are any hindrances to performance and to assist the ALJ in improving his or her performance.

If issues cannot be remedied informally, then we take affirmative, and typically progressive, steps to address underperforming ALJs, including counseling, training, mentoring and, as a last resort, disciplinary action. With the promulgation of our “time and place” regulation, we have eliminated arguable ambiguities regarding our authority to manage scheduling, and we have taken steps to ensure that ALJs are deciding neither too few nor too many cases. By management instruction, we are limiting assignment of new cases to no more than 960 cases annually.

Disciplinary Action

Again, I must emphasize that the vast majority of our ALJs are conscientious and hard-working employees who take their responsibility to the public very seriously. For these ALJs, we can rely on current agency measures including training to address any performance issues they may have. Generally, the informal process works, but when it does not, management has the authority to order an ALJ to take a certain case processing action or explain why he or she cannot take such case processing actions. ALJs rarely fail to comply with these orders. In those rare cases where the ALJ does not comply and where appropriate, we pursue disciplinary action.

The current system makes it challenging to address the tiny fraction of ALJs who hear or decide only a handful of cases, fail to decide cases in a legally sufficient manner, allow cases under their control to languish, or otherwise engage in misconduct. A few years ago, we had an ALJ who failed to inform us, as required, that he was also working full-time for the Department of Defense. Another ALJ was arrested for committing a serious domestic assault. More recently, an ALJ failed to follow his managers’ orders to process his cases. We removed these ALJs, but only after completing the lengthy MSPB disciplinary process that lasts several years and can consume over a million dollars of taxpayer resources. In each of these cases, unlike disciplinary action against all other civil servants, the law required that ALJs receive their full salary and benefits until the case was finally decided by the full MSPB—even though the agency could not allow them in good conscience to continue deciding and hearing cases. We remain open to exploring different options to address this matter, while ensuring the qualified decisional independence of ALJs.

I will now explain how our ALJs evaluate disability claims.

How We Determine Disability—The Sequential Evaluation Process

The Act generally defines disability as the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) due to a physical or mental impairment that has lasted or can be expected to last at least one year or to result in death. SGA is defined as significant work, normally done for pay or profit. Under this very strict standard, a person is disabled only if he or she cannot work due to a medically determinable impairment. Even a person with a severe impairment cannot receive disability benefits if he or she can engage in any SGA. Moreover, the Act does not provide short-term or partial disability benefits.

Our process for determining disability is admittedly complicated, but it is necessarily complex to meet the requirements of the law as designed by Congress.

We generally evaluate adult claimants for disability under a standardized five-step evaluation process (sequential evaluation), which we formally incorporated into our regulations in 1978. At step one, we determine whether the claimant is engaging in substantial gainful activity (SGA). The Act establishes the SGA earnings level for people who are blind and requires us to establish the SGA level for other people who are disabled. If the claimant is engaging in SGA, we generally deny the claim without considering medical factors.

If a claimant is not engaging in SGA, at step two, we assess the existence, severity, and duration of the claimant’s impairment or combination of impairments. The Act requires us to consider the combined effect of all of a person's impairments, regardless of whether any one impairment is severe; throughout the sequential evaluation, we consider all of the claimant’s physical and mental impairments individually and in combination.

If we determine that the claimant does not have a medically determinable impairment or that the impairment or combined impairments are “not severe” (i.e., they do not significantly limit the claimant’s ability to perform basic work activities), we deny the claim at the step two. If the impairment is “severe,” we proceed to the step three.

Listing of Impairments

At step three, we determine whether the impairment “meets” or “equals” the criteria of one of the Listing of Impairments (Listings) in our regulations.

The Listings describe for each major body system the impairments considered so debilitating that they would reasonably prevent an adult from working at the level of SGA regardless of his or her age, education, or work experience. The listed impairments are permanent (i.e., expected to result in death or last for a period greater than 12 months).

Using the rulemaking process, we revise the Listings’ criteria on an ongoing basis. The Listings are a critical factor in our disability determination process, and it is our goal to update the Listings every five years. When updating a listing, we consider current medical literature, advances in medicine, information from medical experts, disability adjudicator feedback, and research by organizations such as the Institute of Medicine. As we update the Listings for entire body systems, we also make targeted changes to specific rules as necessary.

If the claimant has an impairment that meets the criteria in the Listings or equals the criteria of any listed impairment in both severity and duration, we allow the disability claim.

Residual Functional Capacity

A claimant who does not meet or equal a listing may still be disabled. The Act requires us to consider how a claimant’s condition affects his or her ability to perform past relevant work or, considering his or her age, education, and work experience, other work that exists in the national economy. Consequently, we assess what the claimant can still do despite physical and mental impairments (i.e., we assess his or her residual functional capacity (RFC)). We perform that RFC assessment after step three and use it in the last two steps of the sequential evaluation.

We have developed a regulatory framework to assess RFC. An RFC assessment must reflect a claimant’s ability to perform work activity on a regular and continuing basis (i.e., eight hours a day for five days a week or an equivalent work schedule). We assess the claimant’s RFC based on all of the evidence in the record, including but not limited to treatment history, objective medical evidence, opinions, and activities of daily living.

We must also consider the credibility of a claimant’s subjective complaints, such as pain. Such decisions are complex. Under our regulations, in evaluating credibility, disability adjudicators must first determine whether medical signs and laboratory findings show that the claimant has a medically determinable impairment that could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms alleged. If the claimant has such an impairment, the adjudicator must then consider all of the medical and non-medical evidence to determine the credibility of the claimant’s statements about the intensity, persistence, and limiting effects of symptoms. The adjudicator cannot disregard the claimant’s statements about his or her symptoms simply because the objective medical evidence alone does not fully support them. However, a claimant’s statements about pain or other symptoms, will not alone establish that he or she is disabled.

The courts have influenced our rules about assessing a claimant’s disability. For example, when we assess the severity of a claimant’s medical condition, we historically have given greater weight to the opinion of the physician or psychologist who treated that claimant. While the courts generally agreed that adjudicators should give special weight to treating source opinions, the courts formulated different rules about how adjudicators should evaluate treating source opinions. In 1991, we issued regulations that explain how we evaluate treating source opinions.7 However, when assessing whether we properly applied the treating source rule, Federal courts have continued to apply varying standards. We focus a significant amount of training on RFC to help ensure that adjudicators follow our policies, regulations, and the law.

Once we assess the claimant’s RFC, we move to the next steps of the sequential evaluation.

Medical-Vocational Decisions

At step four, we consider whether the claimant’s RFC prevents the claimant from performing any past relevant work. We consider a claimant’s past work relevant only if the claimant performed it within the last 15 years, it lasted long enough for the claimant to learn to do it, and it was SGA. If the claimant can perform his or her past relevant work, either as he or she previously performed it or as generally performed in the national economy, we deny the disability claim.

If the claimant cannot perform past relevant work or if the claimant did not have any past relevant work, we move to the fifth step of the sequential evaluation. At step five, we determine whether the claimant, given his or her RFC, age, education, and work experience, can do other work that exists in the national economy. If a claimant cannot perform other work, we will find that the claimant is disabled. If he or she can perform other work that exists in significant numbers in the economy, we deny the claim.

We use detailed vocational rules to minimize subjectivity and promote national consistency in determining whether a claimant can perform other work that exists in the national economy. The medical-vocational rules in our regulations are rooted in the statutory definition of disability and its requirement that we consider age, education, and work experience in conjunction with RFC. When we issued these rules in 1978, we noted that the Committee on Ways and Means in its report accompanying the Social Security Amendments of 1967 said that:

It is, and has been, the intent of the statute to provide a definition of disability which can be applied with uniformity and consistency throughout the nation, without regard to where a particular individual may reside, to local hiring practices or employer preferences, or to the state of the local or national economy.8

The medical-vocational rules, set out in a series of “grids,” relate age, education, and past work experience to the claimant's RFC to perform work-related physical and mental activities. Depending on those factors, the grid may direct us to allow or deny a disability claim. For cases that do not fall squarely within a vocational rule, we use the rules as a framework for decision-making. In addition, an adjudicator may rely on a vocational specialist or vocational expert to identify other work a claimant has the capacity to perform.

As this description of our evaluation process makes clear, a claimant cannot receive disability benefits simply by alleging pain or other non-exertional limitations. We require objective medical evidence and laboratory findings that show the claimant has a medical impairment that: (1) could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms alleged; and (2) when considered with all other evidence, meets our disability requirements.

Hearings and Appeals Process

The Supreme Court has described the administrative process established by SSA and Congress as “unusually protective” of the claimant. 9 Additionally, the Supreme Court has noted that our hearing system is “probably the largest adjudicative agency in the western world.”10 We have over 70 years of experience in administering the hearings and appeals process.

Hearing Level

When a hearing office receives a request for a hearing from a claimant, the hearing office staff prepares a case file, assigns the case to an ALJ, and schedules a hearing. The ALJ reviews the case de novo, meaning that he or she considers the case anew. The ALJ considers any new medical and other evidence that was not available to prior adjudicators. The ALJ will also consider a claimant’s testimony and the testimony of any medical and vocational experts called for the hearing.

In contrast with Federal court proceedings, our ALJ hearings are non-adversarial. Formal rules of evidence do not apply, and the agency is not represented.11 At the hearing, the ALJ serves as fact-finder and decision-maker, and takes testimony under oath or affirmation. The claimant may elect to appear in-person at the hearing or consent to appear via video. The claimant may appoint a representative who may submit evidence and arguments on the claimant’s behalf and call witnesses to testify. The ALJ may call vocational and medical experts to offer opinion evidence, and the claimant or the claimant’s representative may question these witnesses.

If, following the hearing, the ALJ believes that additional evidence is necessary, the ALJ may leave the record open and conduct additional post-hearing development (e.g., the ALJ may order a consultative exam). Once the record is complete, the ALJ considers all of the evidence in the record and decides the case based on a preponderance of the evidence in the administrative record.

A claimant who is dissatisfied with the ALJ’s decision generally has 60 days after he or she receives the decision to ask the AC to review the decision.

Appeals Council

ODAR’s Office of Appellate Operations (OAO) is composed of both adjudicators on the AC and support staff. Upon receiving a request for review, the AC evaluates the ALJ’s decision, all of the evidence of record, including any new and material evidence that relates to the period on or before the date of the ALJ’s decision, and any arguments the claimant or his or her representative submits. The AC may grant review of the ALJ’s decision, or it may deny or dismiss a claimant’s request for review. The AC will grant review in a case if: (1) there appears to be an abuse of discretion by the ALJ; (2) there is an error of law; (3) the actions, findings, or conclusions of the ALJ are not supported by substantial evidence; or (4) there is a broad policy or procedural issue that may affect the general public interest. The AC will also grant review if there is new and material evidence relating to the period on or before the date of the hearing decision that results in the ALJ’s action, findings, or conclusion being contrary to the weight of the evidence currently in the record.

If the AC grants a request for review, it may uphold part of the ALJ’s decision, reverse all or part of the ALJ’s decision, issue its own decision, remand the case to an ALJ, or dismiss the original hearing request. When it reviews a case, the AC considers all of the evidence in the ALJ hearing record (as well as any new and material evidence), and when it issues its own decision, the AC bases the decision on a preponderance of the evidence.

If the AC makes a decision, it is our final decision. If the AC denies the claimant’s request for review of the ALJ’s decision, the ALJ’s decision becomes our final decision. If the claimant completes our administrative review process and is dissatisfied with our final decision, he or she may seek review of that final decision by filing a complaint in Federal district court. However, if the AC dismisses a claimant’s request for review, he or she cannot appeal that dismissal.

Federal Court Level

A claimant who wishes to appeal an AC decision or an AC denial of a request for review has 60 days after receipt of notice of the AC’s action to file a complaint in Federal district court.

Federal district courts consider two broad inquiries when reviewing one of our decisions: (1) whether we correctly followed the Act and our regulations; and (2) whether our decision is supported by substantial evidence of record. On the first inquiry-whether we have applied the correct law-the court typically will consider issues such as whether the ALJ applied the correct legal standard for evaluating the issues in the claim, such as the credibility of the claimant’s testimony or the treating physician’s opinion, and whether we followed the correct procedures.

On the second inquiry, the court will consider whether the factual evidence developed during the administrative proceedings supports our decision. The court does not review our findings of fact de novo, but rather, considers whether those findings are supported by substantial evidence. The Act prescribes the “substantial evidence” standard, which provides that, on judicial review of our decisions, our findings “as to any fact, if supported by substantial evidence, shall be conclusive.” The Supreme Court has explained that substantial evidence means “such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion.”12 The reviewing court will consider evidence that supports the ALJ’s findings as well as evidence that detracts from the ALJ's decision. However, if the court finds there is conflicting evidence that could allow reasonable minds to differ as to the claimant’s disability and the ALJ’s findings are reasonable interpretations of the evidence, the court must affirm the ALJ's findings of fact.

If, after reviewing the record as a whole, the court concludes that substantial evidence supports the ALJ’s findings of fact and the ALJ applied the correct legal standards, the court will affirm our final decision. If the court finds either that we failed to follow the correct legal standards or that our findings of fact are not supported by substantial evidence, the court typically remands the case to us for further administrative proceedings or, in rare instances, reverses our final decision and finds the claimant eligible for benefits.

Conclusion

Making disability decisions for Social Security programs is a challenging task. Our highly-trained disability adjudicators follow a complex process for determining disability according to the requirements of the law as designed by Congress.

Our appeals process is one of the largest administrative adjudicative systems in the world. The ALJ corps is at the heart of our hearing process, and the vast majority of our ALJs are dedicated public servants who strive to provide the excellent, high-quality service the American public deserves. As I have explained in my testimony, we have made huge strides in the last few years to improve the quality and timeliness of our hearing decisions. Nevertheless, we understand that there is more to do. We are continuing our efforts to ensure that our policy guidance is clear and the application of policy is consistent and uniform as we administer our disability programs.

I thank you for your interest in this matter.

__________________________________________

1 Under the Social Security Act (Act), we administer two major programs that provide cash benefits to persons who are disabled and unable to sustain work: the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program and the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. The SSDI program provides benefits to disabled workers and to their dependents.

2 Today, our Office of Disability Adjudication and Review (ODAR) manages the hearings and AC levels of the administrative review process. Currently, we employ 1,504 ALJs, who work in over 160 offices across the Nation.

3 Six years ago, we defined an aged case as one waiting over 1,000 days for a decision; we have since lowered the threshold to 700 days.

4 The phrase “qualified decisional independence” comes from case law interpreting the Administrative Procedure Act. See e.g., Nash v. Califano, 613 F.2d 10, 15 (2nd Cir. 1980) (“It is clear that these provisions confer a qualified right of decisional independence upon ALJs.”).

5 The MSPB makes this finding based on a record established after the ALJ has an opportunity for a hearing. 5 U.S.C. § 7521

6 Nash v. Bowen, 869 F.2d 675, 680 (2nd Cir. 1989), cert. denied, 493 U.S. 812 (1989).

7 Under those regulations, we will give controlling weight to a treating physician's opinion regarding the severity of the claimant’s medical condition if it is well supported by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques and is not inconsistent with the other substantial evidence in the record. If these conditions are met, a disability adjudicator must adopt a treating source's medical opinion regardless of any finding he or she would have made in the absence of the medical opinion. However, the determination of disability is an issue reserved for the agency, and we will not adopt a treating source’s opinion that a claimant is disabled.

8 43 Fed. Reg. 55349, 55350 (1978) (quoting H.R. Rep. No. 544, 90th Congress, 1st Sess., at 30 (1967)).

9 Heckler v. Day, 467 U.S. 104 (1984).

10 Heckler v. Campbell, 461 U.S. 458, 461 n.2 (1983).

11 During the 1980s, we piloted an agency representative position at select hearing offices. However, a United States District Court held that the pilot violated the Act, intruded on qualified decisional independence, was contrary to congressional intent that the process be “fundamentally fair,” and failed the constitutional requirements of due process. Salling v. Bowen, 641 F. Supp. 1046 (W.D. Va. 1986). We subsequently discontinued the pilot due to the testing interruptions caused by the Salling injunction and general fiscal constraints.

We experienced significant congressional opposition once the pilot began. For example, members of Congress introduced legislation to prohibit the adversarial involvement of any government representative in Social Security hearings, and 12 Members of Congress joined an amicus brief in the Salling case opposing the project.

12 Richardson v. Perales, 402 U.S. 389 (1971).