HEARING ON THE EFFECTS OF COVID-19 ON SOCIAL SECURITY

Testimony by Stephen C. Goss, Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration

House Ways and Means Subcommittee on Social Security

July 17, 2020

Chairman Larson, Ranking Member Reed, and members of the committee, thank you very much for the opportunity to speak to you today about the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on Social Security. The magnitude and duration of effects from the pandemic on our society, the economy, and Social Security are still very uncertain.

The largest immediate effects for Social Security will be from reductions in employment, earnings, and payroll tax liability in the near term, as is true for purely economic recessions. However, unlike in most economic recessions, the potential effects from increased Social Security benefit applications will be partially offset by increased deaths among our beneficiaries due to the pandemic. It is still too early to determine how long the pandemic will continue and what the longer-term effects will be on the level of economic activity and employment, and on the wellness (morbidity) and longevity (mortality) of our population.

The 2020 Social Security Trustees Report was released on April 22, 2020, with assumptions having been selected earlier, not anticipating implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many have speculated about the course of the pandemic since that time, but all such speculation should be viewed only as potential scenarios. For example, in a webinar with the Bipartisan Policy Center on April 23, I described two simple potential scenarios. First, if total earnings in 2020 were reduced to 15 percent below the Trustees’ intermediate projection, with full recovery to expected earnings in 2021 and thereafter, then payroll tax revenue would be reduced by about $150 billion in 2020. In addition, the trust fund reserve depletion date for the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds would likely move from early in 2035 to around the middle of 2034. Second, if earnings were instead reduced by 15 percent for both 2020 and 2021, with full recovery for 2022 and thereafter, then the reserve depletion date would likely move to early in 2034 or late in 2033.

At this time, it appears that the scenarios described above may be too pessimistic for 2020 earnings and that payroll tax liability is on track to be reduced less than 15 percent below the Trustees’ intermediate projection for 2020. For now, it appears that a scenario with 10-percent lower-than-expected earnings and payroll tax liability for 2020 is more likely. Assuming we do not have a substantial second wave of cases from the virus in the fall, with substantial closure of the economy, recovery during 2021 might be expected. The degree of longer-term persistent effects on the level of economic activity and on mortality is as yet unknowable. In the absence of a permanent reduction in the level of economic activity for years after recovery in 2021, the combined trust fund reserve depletion date might be advanced by up to a year, or early in 2034. But if closure due to the pandemic extends through 2021, or if there is a permanent reduction in the level of economic activity after recovery from this recession (as has been the case for some recent economic recessions), then the negative effects on the actuarial status of the combined OASI and DI Trust Funds could be substantially larger.

Comparison to the Recent “Great Recession” of 2007-09

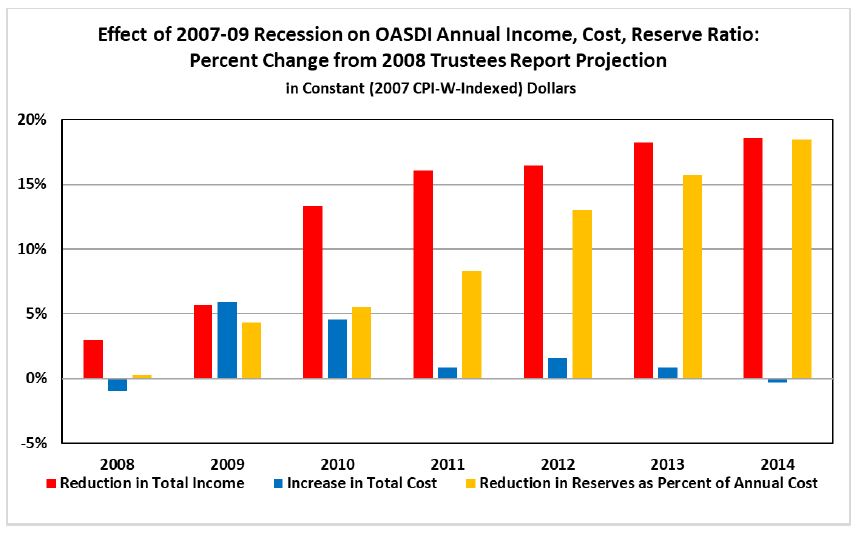

The most recent prior recession started in December 2007, with a gradual rise in the unemployment rate reaching 5.8 percent for 2008, and a peak of 9.6 percent for 2010. As shown in the chart below, reductions in annual trust fund income grew gradually, exceeding 10 percent for 2010 and 15 percent thereafter, compared to the intermediate projection in the 2008 Trustees Report. However, annual program cost (almost entirely benefit payments) exceeded the 2008 Trustees Report projection by only about 5 percent for 2009 and 2010, with little difference thereafter. Increased benefit cost occurred with a delay due to extended unemployment insurance payments, encouraging many individuals who became unemployed to defer application for Social Security until unemployment payments ceased, or even later as they returned to work.

Due to the extended and sustained reduction in income to the trust funds, the combined trust fund reserves at the beginning of 2015 fell short of the level of 393 percent of annual program cost that was projected in the 2008 Trustees Report, reaching an actual level of 311 percent. As a result, the projected reserve depletion date for the combined funds changed from 2041 in the 2008 Trustees Report to 2034 in the 2015 Trustees Report. The reserve depletion date improved slightly to 2035 by the 2020 Trustees Report, based largely on lower disability incidence rates. In the 2007-09 recession, increased benefit cost from earlier, and in some cases increased, applications for Social Security benefits had a relatively small effect on the actuarial status of the trust funds, as we expect will be the case for the current recession.

For the current recession, the reduction in business activity and employment was extremely abrupt in the spring of 2020, resulting in a more immediate drop than in the 2007-09 recession. However, economic activity could recover almost as abruptly late this year, or through 2021, depending on the spread of the virus, availability of vaccines and therapies, and responses by governments and individuals. If there is a quick recovery, then the combined OASI and DI Trust Fund reserve depletion date might change by less than one full year, from early in 2035 to sometime in 2034. However, if the pandemic persists with a continued or even permanent reduction in the level of economic activity, then the effect on the actuarial status of the trust funds will be larger.

Implications for the National Average Wage Index (AWI) and Future Benefit Levels

The Social Security benefit formula is designed to increase the level of monthly benefits for workers who become newly eligible in each year, compared to the benefit level for workers who became newly eligible in the prior year, by the increase in the average wage level for 2 years earlier. This approach maintains the relationship between monthly benefit levels and career-average earnings; in other words, it maintains the benefit “replacement rate” across generations.

This indexation of the benefit formula does not guarantee an increase in the benefit level from one generation to the next. The design of the national average wage index (AWI) makes it susceptible to variation due to changes in employment, because the AWI is determined based on the ratio of total wages paid in the year to the total number of workers in the year. The denominator of the ratio, the number of workers in the year, includes all workers who were employed at any time during the year, regardless of the amount of time they were employed. Thus, in an economic recession, when many workers might work for less than the entire year, the AWI will tend to increase less than in a typical year, and can even decline.

Because wages for a given year are not fully reported until well into the following calendar year, there is a two-year lag between the year of the AWI and the year for which it is actually used. For example, the AWI for 2020 will not be known with certainty until late in 2021, and it will not be used for Social Security benefit calculations prior to 2022.

In 2009, due to the recession, the AWI failed to increase from the level of the prior year for the first time. The AWI for 2009 declined to 1.5 percent below the AWI level for 2008. This affected the benefit levels for all Social Security beneficiaries with initial benefit eligibility in 2011, because workers’ earnings and the PIA formula bend points used in benefit computations are wage indexed up through the second year prior to their initial benefit eligibility. As a result, the 2011 benefit for workers who became newly eligible in 2011 was 1.5 percent less than the 2010 benefit for workers with similar career earnings who became newly eligible in 2010. That reduction will persist for the lifetime of those workers who became newly eligible in 2011. While policymakers did recognize this effect in 2010, no changes were made in the law at that time—mainly because the reduction in the AWI and benefit levels was small, and it was known that the first cost of living adjustment (COLA) applicable for those affected would be relatively large (3.6 percent, versus no COLA in the prior two years).

Experience so far for 2020 suggests that total wages for the year as a whole will be on the order of 10 percent below the level projected in the 2020 Trustees Report, and that the number of workers with any earnings received in 2020 (regardless of how much they worked in 2020) will be about 1 percent lower than projected in the 2020 Trustees Report. If these preliminary estimates are realized, then the average wage used to determine the AWI for 2020 would grow by about 9.1 percent less than projected in the 2020 Trustees Report (0.9/0.99). Because the intermediate assumptions in the 2020 Trustees Report produced a 3.5-percent increase in the AWI for 2020, this means that the 2020 AWI would actually be about 5.9 percent below the level of the 2019 AWI (0.909*1.035). It is important to note that these changes are consistent with the illustrative scenario described in this paragraph, and that actual experience might be very different.

Under current law, a decline in the AWI for 2020 would result in two specific effects on future benefit levels:

As an example of the effects of a decline in the 2020 AWI on benefit levels, consider a newly eligible retired worker beneficiary in 2021 who had earnings at the level of the AWI over his career. Under the intermediate assumptions of the 2020 Trustees Report, this worker would be eligible for a monthly primary insurance amount (PIA) of about $2,000 in 2021 (subject to a reduction for early retirement). For a similar newly eligible beneficiary in 2022, the PIA in 2022 was projected to be 3.5 percent higher than $2,000, or about $2,070. Under the illustrative scenario, where the AWI would grow by 9.1 percent less from 2019 to 2020 than had been expected, the monthly PIA for the newly eligible worker in 2022 would be about $1,881, which is about $119 lower than the initial benefit for the worker becoming newly eligible in 2021.

Legislation that Would Avoid Benefit Reductions and Increases Due to a Decline in the AWI

Under the illustrative scenario considered here, the AWI for 2020 would increase by 9.1 percent less than was projected in the 2020 Trustees Report. While that entire 9.1-percent shortfall could be fully restored through legislation, a modified and less costly approach would be to simply avoid any reduction in the AWI from one year to the next for all purposes, and thus avoid any reduction in benefits compared to beneficiaries who became newly eligible in the prior year. A bill using this approach, S. 4180, the “Protecting Benefits for Retirees Act,” was introduced on July 2, 2020, by Senators Tim Kaine and Bill Cassidy. Under the illustrative scenario, this bill would eliminate the reduction in benefits for those becoming newly eligible in 2022 due to the 5.9-percent drop in the AWI from 2019 to 2020, and not the entire reduction in benefits due to the 9.1-percent lower 2020 AWI from the level that was projected in the 2020 Trustees Report. This bill would also eliminate the increase in benefits due to a drop in the AWI between 2019 and 2020 for those who become newly eligible in 2023 and later.

In particular, under this bill, the AWI would not be allowed to decline from one year to the next for benefit computation and other purposes: the AWI used for any year starting with 2020 would be replaced by the highest AWI level determined for any prior year, if higher than the level calculated for the current year. As mentioned above, this legislative change would mean that benefits for workers who become newly eligible in 2022 would be at the same level as similar workers who became newly eligible in 2021, rather than being 5.9 percent lower. This approach would thus avoid about 63 percent of the reduction in lifetime benefits compared to what was projected in the 2020 Trustees Report. In addition, this legislative change would also eliminate most of the roughly 0.15-percent increase in the benefit level for workers in 2020 who become newly eligible for benefits after 2022.

The cost to the OASDI program for this legislative change, applied to the illustrative scenario with a 5.9-percent reduction in the AWI from 2019 to 2020, would be about $49 billion in present value for the period 2020 through 2094. This $49 billion is made up of two partially offsetting effects: about $90 billion in added cost for eliminating the drop in benefits for those who become newly eligible in 2022, and about $41 billion in reduced cost for eliminating the increase in benefits for those who become newly eligible after 2022. The 75-year summarized cost rate would increase by 0.01 percent of taxable payroll over the period). Over the 10 years 2020-2029, the net increase in cost under this illustrative scenario would be about $20 billion in nominal dollars.

H.R. 7499, the “Social Security COVID Correction and Equity Act”

Another legislative option to address potential reductions in the AWI from one year to the next would be to eliminate only the reduction in benefit level due to the drop in the AWI for workers who become newly eligible two years after the AWI decline, and not eliminate the increase in benefits for those who become newly eligible three or more years after the decline. This approach, as proposed in H.R. 7499, the “Social Security COVID Correction and Equity Act,” introduced by Chairman Larson on July 9, 2020, would increase long range OASDI cost by $90 billion in present value dollars for the period 2020 through 2094 (about 0.02 percent of taxable payroll over the period), and would increase the cost over 2020-2029 by about $21 billion in nominal dollars. This approach would retain the relatively small increase in future benefits for workers with earnings in 2020 who first become eligible after 2022. The bill would additionally provide one-year benefit increases for many Social Security beneficiaries and Supplemental Security Income recipients in 2020, and a one-year reduction in income tax liability on Social Security benefits. The estimated cost for these one-year changes for OASDI is about $54 billion in the period 2020-2029. Under this bill, the General Fund of the Treasury would reimburse the OASI and DI Trust Funds for all of the changes in annual costs and revenue for the OASDI program. Thus, enactment of the Bill would have no significant effect on the actuarial status of the combined trust funds.

Conclusion

The unanticipated COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing recession continue to have significant effects on our society, our economy, and the benefits paid and revenues received by the Social Security Trust Funds. The magnitude and duration of these effects are as yet unknown. My testimony is intended to provide some perspective on the possible effects of the pandemic and the recession on the financial status of the Social Security program, using a purely illustrative scenario. This illustrative scenario also allows us to explore the implications of a potential drop in the AWI on Social Security benefits, and proposals that would address the resulting implications on benefit levels for millions of workers. Estimates provided under this illustrative scenario reflect the effects of a potential reduction in the AWI from one year to the next only from 2019 to 2020. While such reduction has been rare (only seen from 2008 to 2009 since the AWI was first utilized in 1951), it is likely that some future recessions will cause such reductions. In addition, it is also possible that the AWI for 2021 could remain below the level of the 2019 AWI.

As mentioned earlier, the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic were not reflected in the 2020 Trustees Report. We will be working between now and next April with the Trustees and their staffs to fully reflect the effects of the pandemic and the recession in the 2021 Trustees Report.

Thank you again for the opportunity to talk to you today. I look forward to answering any questions you may have.