Testimony of Marianna Lacanfora, Acting Deputy Commissioner

Office of Retirement And Disability Policy

Social Security Administration

Regarding Workers' Disability Insurance

Before The Senate Finance Committee

July 24, 2014

Chairman Wyden, Ranking Member Hatch, and Members of the Committee:

Thank you for this opportunity to discuss the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) disability determination process, which is one of the largest administrative adjudicative systems in the world. We are committed to continuing to improve this process for our disability claimants and to being good stewards of the disability programs. I would like to begin by thanking both Chairman Wyden and Ranking Member Hatch for attending the disability briefing we held in May. We hope to sponsor more events that will help inform Members and their staff about the programs we administer. Today, I will provide an overview of the disability determination process. Before doing so, I will briefly discuss the vital programs that we administer.

Introduction

We administer the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance program, commonly referred to as "Social Security," which protects against loss of earnings due to retirement, death, and disability. Social Security provides a financial safety net for millions of Americans—few programs touch as many American lives. We also administer the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program, funded by general revenues, which provides cash assistance to persons with very limited means who are aged, blind, and disabled, as defined in the Social Security Act (Act).

Other lesser-known but critical services we provide bring millions of people to our field offices or prompt them to call us each year. For example, we issue replacement Medicare cards and help administer the Medicare low-income subsidy program.

We strive to meet the public’s expectation of exceptional stewardship of program dollars and administrative resources. The payroll tax contributions of individuals and their employers finance the Social Security program, and we recognize it is our responsibility to administer those resources efficiently. Doing so preserves the public’s trust in our programs.

The responsibilities with which we have been entrusted are immense. To illustrate, in fiscal year (FY) 2013 we:

- Paid over $850 billion in Social Security and SSI benefits during the year to a monthly average of more than 62 million beneficiaries, of whom about 15 million received approximately $175 billion in benefits for the year under our disability programs;

- Handled over 53 million transactions on our National 800 Number Network;

- Received over 68 million calls to field offices nationwide;

- Served more than 43 million visitors in over 1,200 field offices nationwide;

- Completed nearly 8 million claims for benefits and nearly 794,000 hearing dispositions; and

- Completed 429,000 full medical continuing disability reviews.

We have a proven track record of providing exceptional service, but it is difficult to maintain without adequate resources. We are a highly efficient organization, and our hard-working employees care deeply about the public they serve.

During FYs 2011-2013, our budget situation was severe. For 3 years in a row, we received nearly a billion dollars less than the President’s budget request. Over those years, we had to make some deep reductions in our services to the public and in our stewardship efforts, while still meeting our mission and serving the public as best as possible. We took the following actions.

- We significantly limited hiring, with only minimal hiring in critical front-line areas;

- Reduced the hours that our field offices are open to the public to allow us to complete late-day interviews without using overtime and to complete retirement and disability claims and other post-entitlement work;

- Operated with minimal, non-personnel spending, only funding our most essential costs, such as mandatory contracts, guard services, and rent on our buildings;

- Closed over 500 contact stations and 7 foreign service posts;

- Increased our use of video hearings to improve service and lower travel costs;

- Suspended our lower priority notices and reduced the number of Social Security Statements issued; and

- Provided more information online to reduce printing and mailing costs.

As a result of significantly limited hiring, wait times in field offices increased, callers to our 800 Number had to wait longer to speak with a representative, and hearings processing time increased. In addition, we were not able to ramp up our cost-effective program integrity efforts as planned.

We are pleased that we received additional resources in FY 2014, and we thank you for your support. As a result, we are able to begin the recovery efforts from 3 years of underfunding. However, it will take time to reverse the impact on services from the years of underfunding. It is critical that we receive the level of funding requested for our agency in the President’s FY 2015 Budget.

General Administrative Review Process

When we receive a claim for disability benefits, we strive to make the correct decision as early in the process as possible so that a person who qualifies for benefits receives them in a timely manner. In most cases, we decide claims for benefits using an administrative review process that consists of four levels: (1) initial determination; (2) reconsidered determination; (3) hearing; and (4) Appeals Council (AC) review. 1 At each level, the decision-maker bases his or her decisions on the Act and our regulations and policies.

In most States, a team consisting of a State disability examiner and a State agency medical or psychological expert makes an initial determination at the first level of review. The Act requires this initial determination. 2 A claimant who is dissatisfied with the initial determination may request reconsideration, which is performed by another State agency team.

A claimant who is dissatisfied with the reconsidered determination may request a hearing. 3 The Act requires us to give a claimant “reasonable notice and opportunity for a hearing with respect to such decision.” 4 Under our regulations, an administrative law judge (ALJ) conducts a de novo hearing unless the claimant waives the right to appear, or the ALJ can issue a fully favorable decision without a hearing; in these cases, the ALJ issues a decision based solely on the written record. 5 If the claimant is dissatisfied with the ALJ’s decision, he or she may request AC review. 6 The Act does not require administrative review of an ALJ’s decision. If the AC decides not to review the ALJ’s decision, the ALJ’s decision becomes our final decision. If the AC issues a decision, the AC’s decision becomes our final decision. 7 A claimant may request judicial review of our final decision in Federal district court. 8

I will now provide an overview of the way we evaluate disability claims.

How We Determine Disability—The Sequential Evaluation Process

The Act generally defines disability, for purposes of programs authorized under the Act, as the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) due to a physical or mental impairment that has lasted or is expected to last at least 1 year or to result in death. SGA is defined as significant work, normally done for pay or profit. Under this very strict standard, a person is disabled only if he or she cannot perform a significant number of jobs that exist in the national economy, due to a medically determinable impairment. Even a person with a severe impairment cannot receive disability benefits if he or she can engage in any SGA. Moreover, the Act does not provide short-term or partial disability benefits.

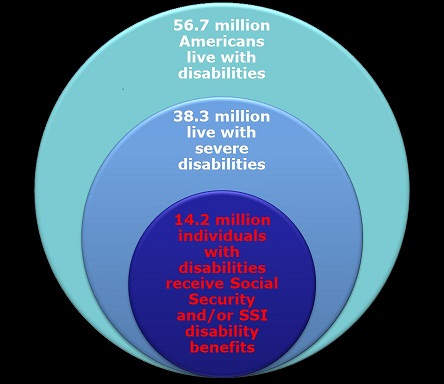

Our process for determining disability is designed to meet the strict requirements of the law as enacted by Congress. As the graphic below demonstrates, due to strict program requirements, disability beneficiaries comprise a significantly smaller subset of the total number of Americans who report living with disabilities, including severe disabilities.

Who are disability beneficiaries?

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and SSA 9

We evaluate adult claimants under a standardized, five-step, sequential evaluation process, which we formally incorporated into our regulations in 1978. The rationale behind our sequential evaluation process is to make certain that our adjudication process covers the key requirements of the statutory definition of disability. At step one, we determine whether the claimant is engaging in SGA. The Act establishes the SGA earnings level for blind persons and requires us to establish the SGA level for other persons. 10 If the claimant is engaging in SGA, we deny the claim without considering medical factors.

If a claimant is not engaging in SGA, at step two we assess the existence, severity, and duration of the claimant’s medically determinable impairment (or combination of impairments). The Act requires us to consider the combined effect of all of a person's impairments, regardless of whether any single impairment is severe. Throughout the sequential evaluation, we consider all of the claimant’s physical and mental impairments singly and in combination.

If we determine that the claimant does not have a medically determinable impairment, or the impairment or combined impairments are “not severe” (i.e., they do not significantly limit the claimant’s ability to perform basic work activities), we deny the claim at the second step. If the impairment is “severe,” we proceed to the third step.

Listing of ImpairmentsAt the third step, we determine whether the impairment “meets” or “equals” the criteria of one of the medical Listing of Impairments (Listings) in our regulations.

The Listings describe for each major body system the impairments considered so debilitating that they would reasonably prevent an adult from doing any gainful activity. The Act does not require the Listings, but we have been using them in one form or another since 1955. The listed impairments are permanent, expected to result in death, or last for a specific period greater than 12 months.

If the claimant has an impairment that meets or equals the criteria in the Listings, we allow the disability claim without considering the claimant’s age, education, or past work experience.

Residual Functional Capacity

A claimant who does not meet or equal a listing may still be disabled. The Act requires us to consider how a claimant’s condition affects his or her ability to perform previous work or, considering his or her age, education, and work experience, other work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy. Consequently, we assess what the claimant can still do despite physical and mental impairments—i.e., we assess his or her residual functional capacity (RFC). We use that RFC assessment in the last two steps of the sequential evaluation.

We have developed a regulatory framework to assess RFC. An RFC assessment must reflect a claimant’s ability to perform work activity on a regular and continuing basis (i.e., 8 hours a day for 5 days a week or an equivalent work schedule). We assess the claimant’s RFC based on all of the evidence in the record, such as treatment history, objective medical evidence, and activities of daily living.

We must also consider the credibility of a claimant’s subjective complaints, such as pain. Under our regulations, disability adjudicators use a two-step process to evaluate credibility. First, the adjudicator must determine whether medical signs and laboratory findings show that the claimant has a medically determinable impairment that could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms alleged. If the claimant has such an impairment, the adjudicator must then consider all of the medical and non-medical evidence to determine the credibility of the claimant’s statements about the intensity, persistence, and limiting effects of symptoms. The adjudicator cannot disregard the claimant’s statements about his or her symptoms simply because the objective medical evidence alone does not fully support them.

We do not consider limitations or restrictions resulting from age, gender, body habitus (e.g., body type and stature), conditioning, or inherent strengths or predispositions attributable to the claimant’s medically determinable impairments. We base our RFC assessment on the individual facts of each claimant’s case, using consistent policy standards.

Once we assess the claimant’s RFC, we move to the next steps of the sequential evaluation.

At step four, we consider whether the claimant’s RFC prevents the claimant from performing any past relevant work. If the claimant can perform his or her past relevant work, we deny the disability claim. “Past relevant work” is generally work that the claimant performed within the past 15 years, lasted long enough for the claimant to learn how to do it, and was SGA.

If the claimant cannot perform past relevant work (or if the claimant does not have any past relevant work), we move to the fifth step of the sequential evaluation. At step five, we determine whether the claimant, given his or her RFC, age, education, and work experience, can do other work that exists in significant numbers in the national economy. If a claimant cannot perform other work, we will find that the claimant is disabled.

We use detailed vocational rules to minimize subjectivity and promote national consistency when we determine whether a claimant can perform other work that exists in the national economy. The medical-vocational rules, set out in a series of “grids,” relate age, education, and past work experience to the claimant's RFC. Depending on those factors, the grid may direct a conclusion to allow or deny a disability claim. For cases that do not fall squarely within a vocational rule, we use the rules as a framework for decision-making. In addition, an adjudicator may rely on a vocational expert or other vocational resources to identify other work that a claimant could perform.

As this description of our evaluation process makes clear, a claimant cannot receive disability benefits simply by alleging pain or other symptoms. As I mentioned earlier, we require objective medical evidence and laboratory findings that show the claimant has a medical impairment that: (1) could reasonably be expected to produce the pain or other symptoms alleged; and (2) when considered with all other evidence, meets our disability requirements.

The Disability Determination Process

A claimant can apply for disability benefits online, by telephone, or in a field office. 11 An SSA claims representative interviews all claimants filing their claims by telephone or in a field office. During this interview, the claims representative explains the definition of disability and our disability claims process and obtains all required applications and forms. When claimants file online, the online application describes the definition of disability and provides an explanation of the claims process, and a field office employee reviews the information the claimant provides. If a claimant’s online application appears incomplete or incorrect, a claims representative will contact the claimant. If a claim does not require a medical determination, the claims representative may make an initial determination. For example, if a claimant seeking Social Security disability benefits is not insured for coverage, the claims representative will deny the claim. In most cases, the claims representative forwards the claim to the State Disability Determination Services (DDS) to make a disability determination.

At the DDS, the claim is assigned to a disability examiner. The examiner requests evidence, schedules follow-ups, confirms that all medical documentation is complete, and determines that there is enough medical evidence to make a disability determination. If the examiner needs additional medical evidence, he or she will re-contact the claimant, re-contact the medical source, or schedule a consultative exam.

Once the examiner decides there is sufficient medical evidence to make a determination, the examiner works with a licensed medical expert or an expert in the field of Psychology to determine whether the claimant is disabled. The type of expert that the disability examiner works with—including their area of specialization—depends upon the nature of the disability alleged by the claimant. When deciding the claim, the examiner and medical or psychological expert must consider all of the evidence in the file and make a determination based on a preponderance of the evidence. In some States, experienced examiners, known as single decision makers, may make certain disability determinations on their own.

If the DDS finds the claimant disabled, we notify the claimant and alert the field office to begin payment effectuation. By statute, 50 percent of the allowances proposed by the DDS undergo a rigorous quality review by our Federal examiners to ensure accuracy prior to payment effectuation.12 If the DDS does not find the claimant disabled, the DDS sends the claimant a denial notice that explains the determination and provides the claimant with additional information, such as how to appeal the determination. Any claimant dissatisfied with the initial determination may appeal it by requesting reconsideration.

Reconsideration

As mentioned earlier, reconsideration generally is the first level of appeal in our disability claims process. The reconsideration determination is a thorough and independent examination of all evidence on record and is made by a different examiner than at the initial level. The disability examiner at the reconsideration level is not bound by the determination made at the initial level.

If the claimant is dissatisfied with the reconsidered determination, the claimant has 60 days after the date he or she receives notice of the determination to request a hearing, which is held before an ALJ. We may extend the 60-day deadline for good cause. A claimant may request an extension of time to file an appeal at every level of agency review and may request an extension of time to file a civil action in Federal court.

Hearings and Appeals Process

The Supreme Court has noted that our hearing system is “probably the largest adjudicative agency in the western world.” 13 We have nearly 75 years of experience in administering the hearings and appeals process. Since the passage of the Social Security Amendments of 1939 (1939 Amendments), the Act has required us to hold hearings to determine the rights of individuals to old-age and survivors’ insurance benefits.

To hold the hearings required by the 1939 Amendments, we established the Office of the Appeals Council (OAC) in 1940. The OAC consisted of 12 “referees” and a Central Office staff. 14 The referees, who heard cases and issued decisions, were located in each of the then-12 regional offices across the country. 15 The Central Office consisted of a three-member AC and a consulting referee. The Chairman of the AC also served as the head of the OAC. To promote uniformity and ensure correct decisions, the AC was authorized to review all referees’ decisions. The 1939 Amendments allowed claimants to appeal our final decisions to Federal court.

After establishing the OAC, we changed the name of that component several times. Since 2006, we have called it the Office of Disability Adjudication and Review (ODAR). ODAR manages the hearings and AC levels of the administrative review process.

Hearing Level

When a hearing office receives a request for a hearing from a claimant, the hearing office staff prepares a case file, assigns the case to an ALJ, and schedules a hearing. The ALJ reviews the case de novo, which means that he or she is not bound by the determinations made at the initial and reconsideration levels. The ALJ considers any new medical and other evidence that was not available to prior adjudicators. The ALJ also considers the claimant’s testimony and the testimony of any medical and vocational experts called for the hearing.

In contrast to Federal court proceedings, our ALJ hearings are non-adversarial. Formal rules of evidence do not apply, and the agency is not represented by an attorney. 16 At the hearing, the ALJ serves as fact-finder and decision-maker, and takes testimony under oath or affirmation. The claimant may elect to appear in-person at the hearing, via video teleconferencing, or by telephone in extraordinary circumstances. The claimant may appoint a representative who maysubmit evidence and arguments on the claimant’s behalf and call witnesses to testify. The ALJ may call vocational and medical experts to offer opinion evidence, and the claimant or the claimant’s representative may question these witnesses.

If, following the hearing, the ALJ believes that additional evidence is necessary, the ALJ may leave the record open and conduct additional post-hearing development (e.g., the ALJ may order a consultative exam). Once the record is complete, the ALJ considers all of the evidence in the record and decides the case based on a preponderance of the evidence in the administrative record.

A claimant who is dissatisfied with the ALJ’s decision generally has 60 days after he or she receives the decision to ask the AC to review the decision.

Appeals Council

Upon receiving a request for review, the AC evaluates the ALJ’s decision, all of the evidence of record, including any new and material evidence that relates to the period on or before the date of the ALJ’s decision, and any arguments the claimant or his or her representative submits. The AC may grant review of the ALJ’s decision, or it may deny or dismiss a claimant’s request for review. The AC will grant review in a case if: (1) there appears to be an abuse of discretion by the ALJ; (2) there is an error of law; (3) the actions, findings, or conclusions of the ALJ are not supported by substantial evidence; or (4) there is a broad policy or procedural issue that may affect the general public interest. The AC will also grant review if there is new and material evidence relating to the period on or before the date of the hearing decision that results in the ALJ’s action, findings, or conclusion being contrary to the weight of the evidence currently in the record.

If the AC grants a request for review, it may uphold part of the ALJ’s decision, reverse all or part of the ALJ’s decision, issue its own decision, remand the case to an ALJ, or dismiss the original hearing request. When it reviews a case, the AC considers all of the evidence in the ALJ hearing record (as well as any new and material evidence that relates to the period on or before the date of the ALJ’s decision), and when it issues its own decision, the AC bases the decision on a preponderance of the evidence.

As mentioned earlier, if the AC makes a decision, it is our final decision. If the AC denies the claimant’s request for review of the ALJ’s decision, the ALJ’s decision becomes our final decision. If the claimant completes our administrative review process and is dissatisfied with our final decision, he or she may seek review of that final decision by filing a complaint in Federal district court. However, if the AC dismisses a claimant’s request for review, he or she cannot appeal that dismissal.

Federal Court Level

In District Court, an attorney usually represents the claimant and attorneys from the United States Attorney’s office or our Office of the General Counsel represent the Government. Whenwe file our answer to the complaint, we also file with the court a certified copy of the administrative record developed during our adjudication of the claim.

The Federal District Court considers two broad inquiries when reviewing one of our decisions:

whether we followed the correct legal standard, and whether our decision is supported by substantial evidence of record. On the first inquiry—whether we have applied the correct law—the court typically will consider issues such as whether the ALJ applied the correct legal standard for evaluating the issues in the claim, such as the credibility of the claimant’s testimony or the treating physician’s opinion, and whether we followed the correct procedures.

On the second inquiry, the court will consider whether the factual evidence developed during the administrative proceedings supports our decision. The court does not review our findings of fact de novo, but rather, considers whether those findings are supported by substantial evidence. The Act prescribes the “substantial evidence” standard, which provides that, on judicial review of our decisions, our findings “as to any fact, if supported by substantial evidence, shall be conclusive.” 17 The Supreme Court has explained that substantial evidence means “such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate to support a conclusion.” 18 The reviewing court will consider evidence that supports the ALJ’s findings as well as evidence that detracts from the ALJ's decision. However, if the court finds there is conflicting evidence that could allow reasonable minds to differ as to the claimant’s disability and the ALJ’s findings are reasonable interpretations of the evidence, the court must affirm the ALJ's findings of fact.

If, after reviewing the record as a whole, the court concludes that substantial evidence supports the ALJ’s findings of fact and the ALJ applied the correct legal standards, the court will affirm our final decision. If the court finds either that we failed to follow the correct legal standards or that our findings of fact are not supported by substantial evidence, the court typically remands the case to us for further administrative proceedings or, in rare instances, reverses our final decision and finds the claimant eligible for benefits.

Disability Research

We are always on the lookout for new partnerships with other agencies and experts to evaluate key aspects of our disability process. Current partnerships include: our collaboration with the National Academy of Science’s Institute of Medicine to revise our disability guidelines to reflect the most up-to-date medical knowledge; our collaboration with the Department of Labor to update our occupational information; our collaboration with the research community (e.g., the Disability Research Consortium) to refine our policy development; and our collaboration with the National Institutes of Health to continue to explore the possible use of computer adaptive testing in the disability program and advance analytic techniques to maximize the accuracy, timeliness, and consistency of decisions.. We also conduct research to improve employment opportunities for our beneficiaries who want to return to work. For example, we are partnering with the Departments of Education, Labor, and Health and Human Services to implement Promoting Readiness of Minors on SSI, or PROMISE. PROMISE is a joint initiative intended to improve the provision and coordination of services and supports for child SSI recipients and their families to enable them to achieve improved educational and employment outcomes and, as a result, reduce the child SSI recipient’s long-term reliance on SSI. The President’s Budget also requests resources and demonstration authority for us to work in partnership with other agencies to test early intervention strategies to help people with disabilities remain in the workforce.Conclusion

Making disability decisions for Social Security programs is a challenging task that has been complicated by deep budgetary cuts in recent years. Our highly trained disability adjudicators follow a complex process for determining disability, consistent with the legal requirements designed by Congress.

The programs we administer demand stewardship that is worthy of their promise of economic security from generation to generation. We are firmly committed to sound management practices and know the continued success of our programs is inextricably linked to the public’s trust in them.

I thank you for your interest in our disability determination process.

____________________________________________________________________________

1 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.900, 416.1400. My testimony focuses on disability determinations, but the administrative review process generally applies to any appealable issue under the programs we administer.

2 Sections 205(b) and 1631(c)(1)(A) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(b), 1383(c)(1)(A).

3 For disability claims, 10 States participate in a “prototype” test under 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.906, 416.1406. In these States, we eliminated the reconsideration step of the administrative review process. Claimants who are dissatisfied with the initial determinations on their disability cases may request a hearing before an ALJ. The 10 States participating in the prototype test are Alabama, Alaska, California (Los Angeles North and West Branches), Colorado, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, New York, and Pennsylvania.

4 Sections 205(b)(1), 1631(c)(1)(A) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(b)(1), 1383(c)(1)(A). A claimant has 60 days after

the date he or she receives notice of the determination to request a hearing before an ALJ.

5 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.929, 404.948, 416.1429, and 416.1448.

6 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.967-404.968, 416.1467-416.1468.

7 The AC can also grant the claimant’s request for review and remand the case to an ALJ. 20 C.F.R. §§ 404.967, 416.1467.

8 Sections 205(g), 1631(c)(3) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(g), 1383(c)(3).

9 For estimates of the number of Americans living with disabilities, including severe disabilities, see http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p70-131.pdf. For the estimate of individuals with disabilities receiving Social Security and/or SSI disability benefits, see http://www.socialsecurity.gov/policy/docs/quickfacts/stat_snapshot/2013-12.html.

10 Generally, countable earnings averaging over $1,070 a month (in 2014) demonstrate the ability to perform SGA. For blind persons, countable earnings averaging over $1,800 a month (in 2014) demonstrate SGA.

11 We do not yet have an online SSI application.

12 Sections 221(c)(3)(C) and 1633(e) of the Act.

13 Heckler v. Campbell, 461 U.S. 458, 461 n.2 (1983).

14 In August 1959, we changed the title of referee to “hearing examiner,” which was the term used in the Administrative Procedure Act of 1946. In 1972, the Civil Service Commission changed this title to “Administrative Law Judge.”

15 We have increased our adjudicatory capacity to address rising workloads. By 1957, we had 75 referees. In 1973, our ALJ corps exceeded 500 judges for the first time. Currently, there are over 1,400 judges in our ALJ corps.

16 During the 1980s, we piloted an agency representative position at select hearing offices. However, a United States District Court held that the pilot violated the Act, intruded on qualified decisional independence, was contrary to congressional intent that the process be “fundamentally fair,” and failed the constitutional requirements of due process. Salling v. Bowen, 641 F. Supp. 1046 (W.D. Va. 1986), vacated as moot, No. 86-2121 (4th Cir. June 15, 1987). We subsequently discontinued the pilot due to the testing interruptions caused by the Salling injunction and general fiscal constraints. We experienced significant congressional opposition once the pilot began. For example, members of Congress introduced legislation to prohibit the adversarial involvement of any government representative in Social Security hearings, and 12 Members of Congress joined an amicus brief in the Salling case opposing the project.

17 Sections 205(g), 1631(c)(3) of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §§ 405(g), 1383(c)(3).