Statement of Carolyn W. Colvin,

Deputy Commissioner,

Social Security Administration

before the Committee on Ways and Means

Subcommittee on Human Resources

July 25, 2012

Chairman Davis, Ranking Member Doggett, and Members of the Subcommittee:

I appreciate this opportunity to appear before the Subcommittee to discuss the lessons learned from the Social Security Administration’s (SSA) management of the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. It has been 40 years since enactment of the Social Security Amendments of 1972, which created the SSI program. Undoubtedly, we have faced a number of significant challenges in administering SSI over the years, but I believe that the record will show that, with the help of this Subcommittee, we diligently manage this complex program.

In 1972, when the SSI program was established, Congress moved the responsibility for administering programs for needy aged, blind, and disabled individuals from the States to the Federal Government to provide a standard floor of income to these vulnerable individuals based on nationally uniform criteria. Congress designated SSA because of our existing infrastructure and reputation for accurate, efficient, and compassionate administration of the Social Security programs.

While there have been several major pieces of legislation changing eligibility provisions in the SSI program, such as the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 and the Foster Care Independence Act of 1999, the basic structure of the SSI program as a cash assistance, means-tested program of last resort has remained unchanged. As described in the Ways and Means report on the originating legislation1:

The new program has been designed with a view toward providing:

- An income source for the aged, blind, and disabled whose income and resources are below a specified level;

- Incentives and opportunities for those able to work or to be rehabilitated that will enable them to escape from their dependent situations; and,

- An efficient and economical method of providing this assistance.

My testimony focuses on the last of these elements. Specifically, I will discuss what we have learned through 40 years of experience in providing assistance under a complex, means-tested program, and how we have used technology and other innovative approaches to efficiently and effectively make sure that only eligible individuals receive the right amount of benefits at the right time. I will highlight some of our recent innovations such as predictive modeling, data exchanges, and data mining, but it is also important to understand that successful administration of the very complex SSI program requires more than just technology; it requires an adequate number of well-trained Social Security staff. I must also note that I will only discuss how we determine eligibility and benefit amounts based on means testing. First, I will begin with a quick overview of the scope of the SSI program.

Our Beneficiaries

In calendar year 2011, 8.1 million aged, blind, and disabled individuals2 received SSI benefits on a monthly basis. For these beneficiaries, SSI is a vital lifeline that enables them to meet their basic needs of food, clothing, and shelter. In 2011, these beneficiaries received more than $49 billion in Federal SSI benefits and an additional $3.5 billion in State supplementary payments.

Slightly more than 2 million of the individuals receiving SSI are aged 65 or older. Of these, roughly half are aged 75 or older. Nearly 70 percent of those over 65 are female and many, if not most, are widowed or never married. SSI is a safety net under Social Security and, in fact, about 2.7 million SSI recipients also receive Social Security benefits. At the other end of the age spectrum, nearly 1.2 million disabled children under age 18 receive SSI benefits.

The 2012 Federal SSI benefit rate is $698 a month, which is about 74 percent of the poverty level. Eligible couples—both of whom are aged, blind, or disabled—receive the Federal benefit rate of $1,048, which is about 82 percent of the poverty level. There are about 281,000 eligible couples receiving SSI.

By any measure, SSI recipients are among the poorest of our citizens. For them, SSI is truly the program of last resort and is the safety net that protects them from complete impoverishment. We must be extremely careful that efforts to improve the program and increase administrative efficiency do not harm these most vulnerable members of our society. However, it is our obligation to the American taxpayer to ensure that payments made under the program are consistent with the program's requirements.

Program Complexity and Program Integrity Efforts

Means-testing adds to the complexity of any program. While the SSI program was never simple, it has become increasingly complex over the years. Congress has enacted a number of changes in response to concerns about how best to address the many events and situations that affect the SSI-eligible population.

Much of the program's complexities stem from the way SSI payments are calculated, which is defined by statute. Two factors used to determine an individual's monthly benefit are income and living arrangements. Income can be in cash or in kind, and is usually anything that a person receives that can be used to obtain food or shelter. It includes cash income such as wages, Social Security and other pensions, and unemployment compensation. In-kind income is food and shelter or something someone can use to obtain those items. Generally, the amount of the cash income or the value of the in-kind income is deducted from the Federal benefit rate, which is currently $698 a month. After disregarding the first $65 of earnings, we deduct $1 for every $2 of earnings. For other income—for example, Social Security—we reduce the benefit dollar-for-dollar after disregarding the first $20.3

Individuals' SSI benefit amounts also may change if they move into a different “living arrangement”—whether a person lives alone or with others, or resides in a medical facility or other institution. For instance, when an individual moves into a nursing home, the person’s monthly payment may be reduced to as little as $30 per month. If the person moves from his or her own household into the household of another person, and that person provides food or shelter, the payment also may be reduced.

The value of an individual’s resources also affects eligibility for the program. An individual is not eligible for benefits if his or her countable resources exceed $2,000, and couples are not eligible if their countable resources exceed $3,000. These resource limits have not been changed since 1989. In general, we count as resources items individuals can convert to cash and use for their support and maintenance, such as bank accounts, stocks, and bonds. Congress has amended the Act several times to add new resources exclusions, further increasing the complexity of the program. Our Application for Supplemental Security Income is a 22-page form that asks applicants questions about these and other issues. I am including a copy as part of my statement.

The design of the SSI program requires that we adjust benefit payments to account for these factors. We explain to SSI recipients that they must report these changes to us when they occur. Absent their timely reporting, it is difficult to obtain information about these changes in a prompt fashion, resulting in some erroneous payments. Additionally, even if individuals report in a timely manner, we are required to first provide written notification of how the change affects their benefit amounts and provide due process protections. This process delays adjusting payments to the correct amount. Furthermore, we generally make SSI payments on the first day of the month for eligibility in that month. Even if the payment is correct when paid, any changes that may occur during the month can affect the payment due, which can result in an overpayment or underpayment. Thus, the program requirements themselves sometimes cause erroneous payments.

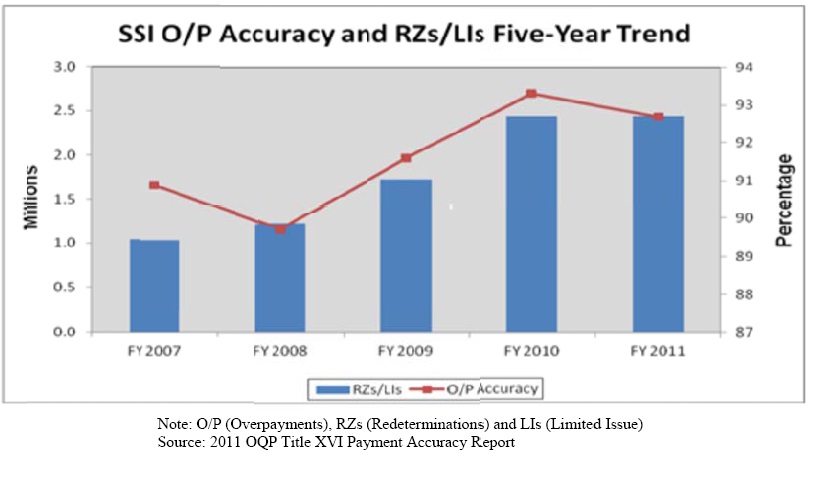

Our overpayment accuracy rate reflects the complex nature of the SSI program. Still, we have improved. In FY 2008, our SSI overpayment accuracy rate was 89.7 percent. We continue to make positive strides; at the end of FY2011 our overpayment accuracy was 92.7 percent. We were able to achieve this improvement in part by increasing the number of redeterminations of eligibility we conduct. Redeterminations are a process we use to re-examine recipients’ income and resources to ensure that they are still eligible for monthly payments. Redeterminations are one of our most powerful program integrity tools. We estimate that every dollar spent on SSI redeterminations yields about $6 in lifetime program savings, including Medicaid program effects. We have steadily increased the number of redeterminations we conduct each year since FY 2007. The following chart reflects the important connection between the number of redeterminations we complete—determined by our funding levels—and the accuracy of the SSI program.

Similar to redeterminations, we also conduct periodic medical continuing disability reviews (CDRs) to evaluate whether disabled SSI beneficiaries continue to meet the medical criteria for disability as required by the Social Security Act. We estimate that, on average, each dollar spent on SSI and Disability Insurance (DI) medical CDRs will yield about $9 in lifetime program savings, including savings accruing to Medicare and Medicaid.

Lesson Learned: Predictive Models Help Prioritize Our Program Integrity Efforts

Predictive modeling techniques have proven to be immensely helpful to ensure that we use our resources effectively and efficiently.

We do not have the resources to conduct redeterminations on all 8.1 million SSI recipients every year. Using our SSI Redetermination Scoring Model, we target the cases most likely to be overpaid. In FY 2011 predictive modeling allowed us to prevent $1.2 billion more in overpayments than what we would have otherwise identified through a random selection of cases.

The model has two parts: the first part predicts the probability that a case has an overpayment error and the second part predicts the potential dollar amount of the overpayment. At the start of every fiscal year, we run all SSI recipients through the model to prioritize error prone cases and schedule a redetermination. We also select for review the records that contain at least one issue that we need to further develop, such as undisclosed wages identified through our computer matching operations. We call these reviews “limited issues.”

To help us determine how to prioritize our CDRs, we employ a series of statistical scoring models to predict the likelihood of medical improvements for adult beneficiaries who receive benefits due to disability. These statistical scoring models are based on our historical disability data and predict the likelihood of medical improvement at a given point in time. The disability data we use to build these scoring models include a wide array of medical, demographic, and disability case-related information. These scoring models allow us to conduct CDRs in a costeffective and efficient manner that is also less burdensome for disability beneficiaries.

Lesson Learned: Automation Helps Employees Focus on the Most Complex Issues

Automation assists our employees by doing some of the more routine work and freeing them up to focus on more complex work that cannot be automated. When we first began administering the SSI program, we stored most case information on paper in a claims folder, and the field office keyed the basic claim data into an electronic telecommunications terminal and transmitted it to the central office computer in Baltimore.

In 1992 we implemented our Modernized Supplemental Security Income Claims Systems (MSSICS), which guides our employees through collecting the information we need to determine eligibility and monthly payment amount. MSSICS also stores the claims file information, which has allowed us to move to fully electronic records.

We continue to modernize the capabilities of this case processing system. We have migrated to a web-based architecture that allows us to provide robust online services and additional time saving features for our employees. It is a gradual process because a complete conversion is a large effort that requires significant IT resources to accomplish.

Under the Social Security Act, we are required to verify from independent sources information supplied by applicants and to obtain from outside sources additional information that might bear on an individual’s eligibility under the program.4 We are constantly trying to expand the pool of such data available to us or make the data available on a more timely or economical basis.

Resources in financial accounts are a leading cause of erroneous payments, and the existence and value of those accounts is one of the most difficult factors to verify. In 1998, we submitted a legislative proposal, which contained a provision requiring SSI applicants and beneficiaries to provide their authorization to obtain all financial records from all financial institutions as a condition of SSI eligibility. With the support of this Subcommittee, the provision was enacted in the Foster Care Independence Act of 1999. After we had the authority to obtain financial information, we needed a mechanism to do so. Therefore, we developed and implemented an innovative approach to access financial information, which we call Access to Financial Institutions (AFI).

We contract with a vendor, Accuity Solutions (“Accuity”) to help us implement and maintain AFI. Accuity is our intermediary with the financial institution community. They recruit financial institutions to participate in AFI, train them, handle all communications, and troubleshoot when issues arise. They also reimburse the banks for the costs associated with supplying account data.

We recently integrated the AFI process into our SSI case processing system, which has allowed us to automatically obtain financial account information. This electronic process also enables us to check for undisclosed accounts at randomly-selected financial institutions located near the recipient’s address.

We are always looking for smarter ways to handle our work. Building upon our AFI success, we are exploring the use of commercial databases to help us identify undisclosed non-home real property held by SSI applicants and recipients. This automated approach has the potential of helping us uncover unreported assets and improve the accuracy and integrity of the SSI program.

Lesson Learned: Automation Can Make it Easier for Our Beneficiaries

Wages are the second leading cause of improper payments in the SSI program. The SSI benefit is highly sensitive to fluctuations in income. SSI recipients must report changes in their wage amounts to us. However, recipients do not always report wages to us on a timely basis. Easy-to-access automation tools helps our beneficiaries report changes that may affect their benefits. We created the SSI Telephone Wage Reporting System (SSITWR) to provide recipients with an easy way to report their wages to us that would also save resources by updating our records directly without requiring employee handling. The SSITWR system allows recipients to report their monthly wages using a toll-free, touch tone telephone system. When recipients report wages through SSITWR, the system automatically updates the SSI record, corrects the upcoming payment, if necessary, and issues a receipt to the caller.

Our tests have shown that the wage information we receive through SSITWR is highly accurate. Nevertheless, we crosscheck SSITWR reports against the wage information from the Office of Child Support Enforcement’s National Directory of New Hires (NDNH) and our Master Earnings File.

We are currently developing an SSI Mobile Wage Reporting application, an extension of the SSITWR system, which will provide SSI recipients the ability to submit their wages via their mobile smart phones. Like its telephone counterpart, the mobile application will automatically update the SSI record, correct the upcoming payment, if necessary, and issue a receipt to the individual.

When recipients work but do not regularly report their wages, we must obtain the wage information directly from their employers. We are constantly searching for methods of quickly and efficiently gathering this information. We recently contracted with The Work Number, a large payroll processor, to provide us with immediate and online access to their large database of wages covering over 2,400 employers. Although we have been using The Work Number’s services for some time, our new contract allows us to obtain more information immediately, saving our employees’ time.

Lesson Learned: Electronic Data Matches Improve Our Program Integrity Efforts

Data exchanges are a cost-effective way to prevent and detect improper payments. For example, in FY 2008, for every dollar we spent on our quarterly wage match with the Office of Child Support Enforcement we saved about $7 in SSI benefits.

We often verify the income and resources used in the SSI means test through data matches. Efficient, accurate, and timely exchanges of data promote good stewardship for all parties involved. We have over 1,500 exchanges with a wide-range of Federal, State, and local entities that provide us with information that we need to stop benefits completely or to change the amount of benefits we pay. For example, our exchange with the Office of Child Support Enforcement provides us with wage information, our exchange with the Internal Revenue Service provides us with data on income and asset ownership, and our exchange with the Department of Homeland Security provides us with data on recipients who have voluntarily left the country or have been deported. We also have about 2,300 exchanges with prisons that allow us to suspend benefits to prisoners quickly and efficiently.

We are bound by the Computer Matching and Privacy Protection Act, which requires us to independently verify and give due process before we adjust payment based on the information we obtain through interfaces. However, three of our matches– Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Personnel Management, and Railroad Retirement Board– qualify for an exception from the requirements of the CMPPA and automatically update SSI records and adjust payment amounts. The rest of our interfaces create alerts our employees must investigate and resolve.

We appreciate the efforts made by the Chairman and members of the Subcommittee to establish uniform data exchange standards for certain Federal programs. We look forward to working with Congress to determine how best to establish uniform data exchange standards while promoting efficiency and maintaining security of our beneficiaries’ private information.

Simplifying SSI

Tension exists between aspects of the SSI program and administrative efficiency. As I mentioned, the complexity of the SSI program is rooted in the requirement to determine eligibility using an extensive set of rules covering income, resources, living arrangements, and, for beneficiaries under age 65, a disability requirement. The program is designed to be responsive to the beneficiaries’ changing circumstances and requires that they report any changes that may affect their eligibility or the amount of their monthly benefit.

Technology goes a long way in helping us administer the complex SSI program. However, technology and trained staff alone cannot eliminate the complexity. Over the years, we have undertaken a number of initiatives to simplify SSI both administratively and through legislative proposals, and Congress has acted on many of our proposals. While the enacted simplification proposals have been relatively minor in scope, they have had an incremental positive effect. However, significant fundamental program simplification efforts are difficult to achieve.

We will continue to search for ways to simplify SSI to make it easier for our beneficiaries to understand and easier for us to administer.5 More immediately, Congress could help disabled individuals understand and navigate the complex disability work incentive provisions of SSI and the Social Security Disability Insurance programs by reauthorizing the Work Incentive Planning and Assistance (WIPA) and the Protection and Advocacy for Beneficiaries of Social Security (PABSS) programs. These programs have been reauthorized several times since they were created by the 1999 Ticket to Work legislation, but the most recent reauthorization was allowed to lapse at the end of Fiscal Year 2011. In January, we sent a draft bill to Congress to continue the programs.6 We look forward to working with the subcommittee to continue to address this challenge.

Adequate Funding is Critical

In FYs 2011 and 2012, the difference between the President’s Budget and our appropriation was greater than in any other year of the previous two decades. In FY 2011, Congress rescinded $275 million from our information technology (IT) carryover funding, which will hamper our efforts to improve our productivity through IT innovation. In FY 2012, Congress did not fully fund program integrity at the levels authorized by the Budget Control Act, limiting our ability to carry out required program integrity work.

For FY 2013, we are requesting $11.760 billion for our administrative expenses, a modest increase from FY 2012, which includes the program integrity cap adjustments authorized by the Budget Control Act, and which would put Social Security on a ten-year path to eliminate the backlog in program integrity reviews.

Our FY 2013 budget request is lean. We have already curbed lower priority activities so that we can pursue two of our most important goals – eliminating the hearings backlog and focusing on program integrity work. It will be a challenge to achieve the goals associated with these priorities. We expect to lose 2,500-3,000 employees in FY 2012 on top of the more than 4,000 employees we already lost in FY 2011 due to prior budget cuts. At the end of this year, the agency will have about the same number of employees that we had in 2007 even though our work has increased dramatically.

I urge Congress to pass this level of funding because we have proven that we deliver. Through the hard work of our employees and technological advancements, we have increased employee productivity by an average of about four percent in each of the last five years. Few, if any, organizations have accomplished similar improvements.

Conclusion

We are always working on improving our administration of the SSI program, focusing on how technology can make us more efficient. In the future, we are looking to offer mobile and online applications for reporting wages, online change of address and direct deposit, expanded use of Lexis-Nexis to verify real property, and numerous other projects designed to improve our service and ensure the integrity of our payments. Of course, these improvements depend on sustained and adequate funding to support them.

Ultimately, the administration of the SSI program, due to its complexity, remains labor-intensive. While modern technology has enabled us to incorporate new processes and new data sources, our employees are essential to ensuring the integrity of the SSI program. Our employees do a great job navigating the complexity of this program and quickly delivering accurate benefits to people who desperately need them, all with great compassion and skill.

Thank you and I am happy to answer any questions you may have.

Attachment: Application for Supplemental Security Income (SSA-8000)

______________________________________________________

1 House Report No. 92-231, page 147

2 Although the number of disabled recipients has risen in recent years, our allowance rates have not. In fact, our hearing level allowance rate dropped 5 percentage points in FY 2011 and another 5 percentage points so far this fiscal year.

3 The dollar amounts of the disregards in the previous two sentences have not changed since the originating SSI

legislation was enacted in 1972.

4 Section 1631(e)(1)(B)(i)

5 A legislative proposal in the President’s FY 2013 budget would conform the treatment of certain Federal, State, and local tax credits, which are now treated differently depending on the source of the credits. The proposal would simplify SSI policy and eliminate the administrative costs of determining whether such credits are excluded Federal payments or countable State or local payments.

6 A copy of that bill may be found at:

http://www.socialsecurity.gov/legislation/Social%20Security%20Work%20Incentive%20Amendments%20of%202012.pdf .