Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration

before the

House Committee on Ways and Means,

Subcommittee on Social Security

December 2, 2011

Chairman Johnson, Ranking Member Becerra, and members of the subcommittee, thank you very much for the opportunity to speak to you today about the Social Security Disability Insurance program. I would like to share thoughts on three topics: (1) the nature of disability insurance; (2) the financial status of the Disability Insurance program; and (3) the “drivers” of the cost of the Disability Insurance program.

(1) The Nature of Disability Insurance

Disability insurance is arguably the most difficult form of insurance to administer. It is easy to determine whether an insured person has reached retirement age or has died. It is also easy to determine whether a car is wrecked or a house destroyed. It is even relatively easy to determine if health insurance should cover doctor and hospital bills. However, disability is by nature a very subjective concept. Whether a “medically determinable impairment” eliminates the ability to engage in any “substantial gainful activity” depends on a myriad of issues related to a person’s residual functional capacity, past job experience, desire to work, and availability of suitable jobs. All of these issues differ among individuals, across geographic regions, and over time.

The determination of whether a person is disabled is a highly complex process subject to human judgment by the claimant, their representative, the claim examiner, and the medical consultant. Becoming disabled can be a gradual process. A person may not qualify when they initially apply, but may “cross the threshold” of disability during the appellate process or at a subsequent age resulting in reapplication. Initial disability determinations and periodic continuing disability reviews make administration of the Disability Insurance program an enormous challenge. The Social Security Administration meets this challenge effectively and efficiently. Accuracy rates in determinations are high, and multiple appeal steps are available to claimants. Yet, less than 2.5 percent of program expenditures are for administrative expense.

(2) The Financial Status of the Disability Insurance Program

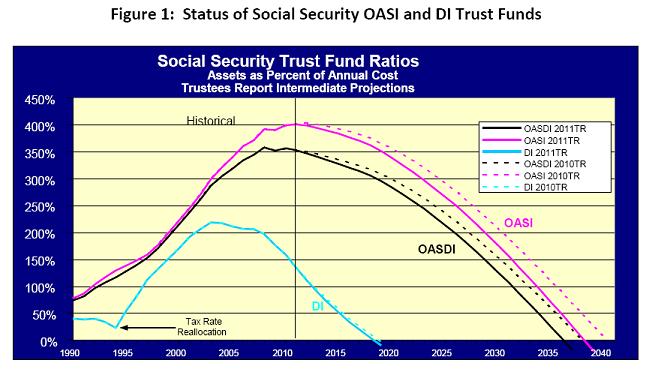

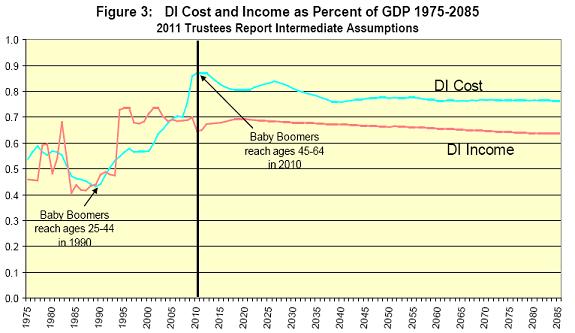

The Disability Insurance Trust Fund assets expressed as a percent of annual program cost peaked in 2003. The 2011 Trustees Report projects assets to become exhausted in 2018, with continuing tax revenue sufficient to pay 86 percent of scheduled benefits thereafter. The unexpectedly large COLA for December 2011 and a lower-than-expected increase in average earnings for 2010 may exhaust trust fund reserves even earlier. For 2085, the Trustees Report projects continuing tax revenue will be sufficient to pay 83 percent of scheduled benefits.

Sustainable solvency can be restored for the Disability Insurance program with a 16-percent reduction in benefits, a 20-percent increase in revenue, or some combination of these changes. Even in the absence of such change, a simple tax-rate reallocation between OASI and DI, as was

done in 1994, could equalize the financial prospects of the trust funds. We estimate that temporarily raising the Disability Insurance program’s share of the 12.4-percent OASDI payroll tax rate from 1.8 to 2.2 percent for 2012 through 2024 and to 2.0 percent for 2025 through 2029 would make scheduled benefits payable for both OASI and DI beneficiaries until 2036.

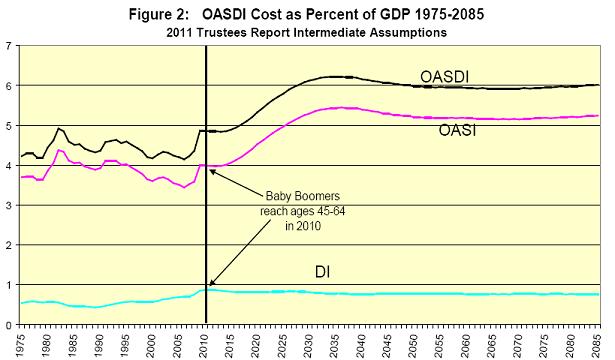

Overall OASDI cost will rise over the next 20 years as the baby boomers retire and are replaced in the working ages with lower-birth-rate generations born after 1965. The drop in birth rates after 1965 will cause a permanent shift in the age distribution of the population with fewer workers to support more elderly retirees.

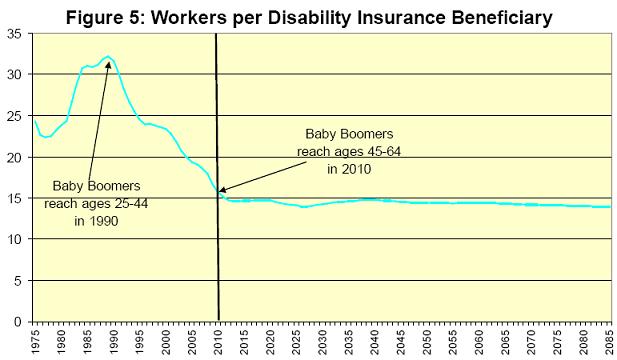

However, the baby boomers already moved from young ages (25-44) in 1990, where few were disabled, to older ages (45-64) in 2010, where many more are disabled. Thus, the 20-year demographic shift in the age-distribution of the population has already occurred for DI.

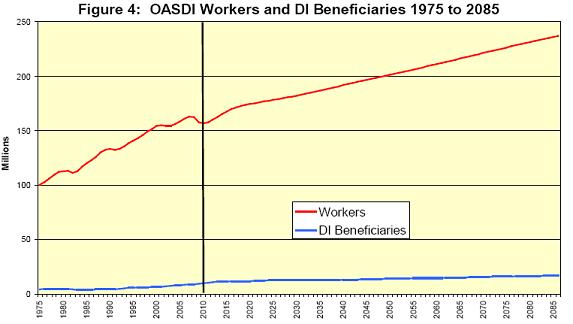

Lower birth rates slow population growth at all ages. We project similar but slower growth rates in both the workforce and DI beneficiaries for the future.

As a result, the number of workers per DI beneficiary is expected to be relatively stable in the future. This means that restoring sustainable solvency for the DI program will not require continually greater benefit cuts or revenue increases. A one-time change to offset the drop in birth rate is all that is needed to sustain the DI program for the foreseeable future.

(3) The “Drivers” of the Cost of the Disability Insurance Program

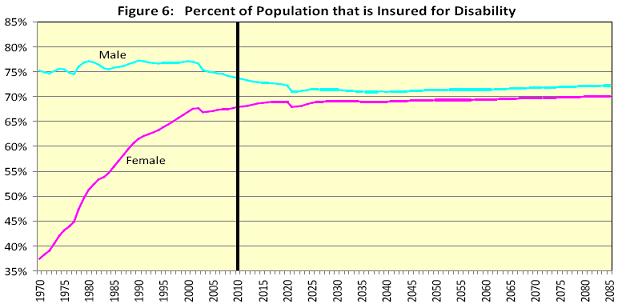

Several drivers specific to DI program cost will be changing in the future. The first important driver is the size of the disability-insured population. Since 1970, this population grew explosively as increasing numbers of women worked consistently and stayed insured.

In the future, we project that men will be less likely to be insured, reflecting increased restrictions on undocumented aliens after 2001, and insured rates for women will stabilize close to men. This change will substantially slow the growth in the cost of the DI program.

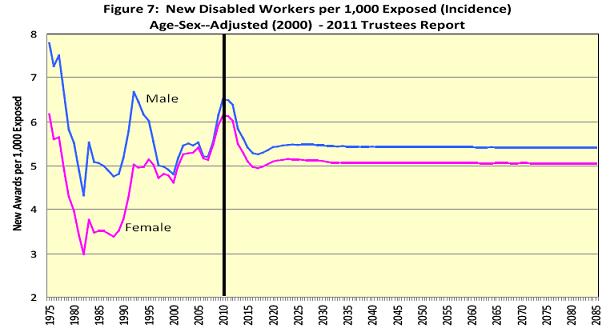

The second important driver of DI cost is rate at which insured workers become newly disabled. Changes in the rate of disability incidence are best seen by excluding the effects of any change in the age-distribution of the general population. For men, this age-adjusted incidence rate has averaged somewhat over five new disability awards per thousand exposed (insured but not already disabled) workers and has seldom been below this level. Since 1980, the age-adjusted incidence rate for women has been moving up to a level much closer to men. We expect that male and female age-adjusted disability incidence rates will be fairly stable in the future.

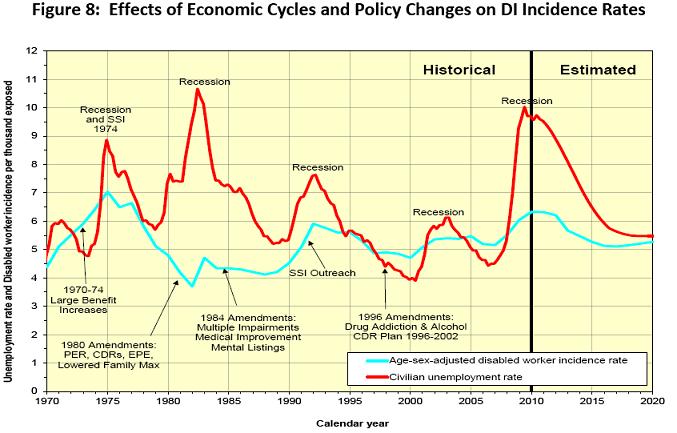

A more careful look at past fluctuations in the overall age-sex-adjusted disability incidence rate reveals a number of specific economic and policy drivers that have influenced disability cost. Periodic economic recessions, as illustrated by the civilian unemployment rate in bright orange in the figure below, have been associated with temporary increases in disability incidence.

The very recent recession of 2008-2009 resulted in an increase in disability incidence that was exceeded only by the incidence rate in 1975. One apparent exception to the relationship between disability incidence and economic recessions is the strong recession of 1981-1982. Here the effect of the recession appears to have been offset by the net effects of the 1980 Amendments, which: (1) sharply increased the levels of pre-effectuation review of disability allowances and continuing disability reviews of current beneficiaries; (2) introduced the extended period of disability to encourage work; and (3) lowered the maximum family benefit for DI beneficiaries.

Additional policy changes over the years had significant effects on disability incidence. Double-digit ad-hoc benefit increases in 1970 through 1974 made disability benefits more attractive. The 1984 Amendments may have countered the effects of a strong economic recovery with increased emphasis on multiple impairments and mental listings, and requirement to show medical improvement for benefit cessation. The SSI outreach to disabled adults likely added to the effects of the 1990-1991 recession. Also, the 1996 Amendments may have partially counteracted the effects of a strong economic recovery with elimination of drug addiction and alcoholism as disabling impairments, and effecting a 7-year plan to eliminate a backlog of continuing disability reviews. Future policy changes and economic cycles will undoubtedly continue to cause fluctuations in disability incidence rates.

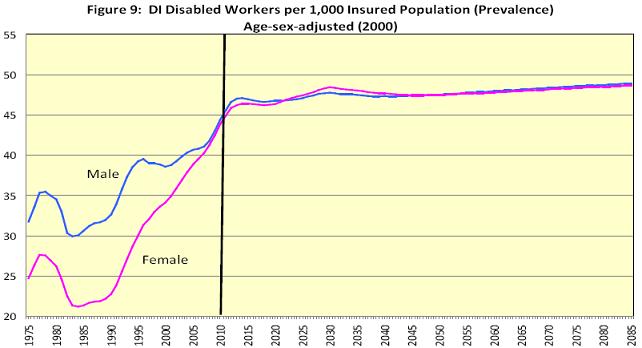

Disability incidence rates tell us the rate at which healthy workers become newly disabled. The cost of providing benefits to disabled workers also depends on how long their disability lasts. Disability incidence and length of the period of disability can be combined by considering the number of insured workers who are currently disabled at each age, regardless of how long ago they became newly disables. Disability prevalence rates are simply the percent of the insured population at a given age that is currently receiving disabled worker benefits, regardless of when benefits started. Age-sex-adjusted disability prevalence rates eliminate the effects of changing population age distribution and isolate the effects of disability-specific drivers.

The figure above shows that the age-sex adjusted disability prevalence rate for men increased by about a third between 1990 and 2010, even though age-sex-adjusted incidence rates were fairly stable over the observed period 1970-2010. Female prevalence rates increased even more because their age-sex-adjusted incidence rates did increase over the observed period.

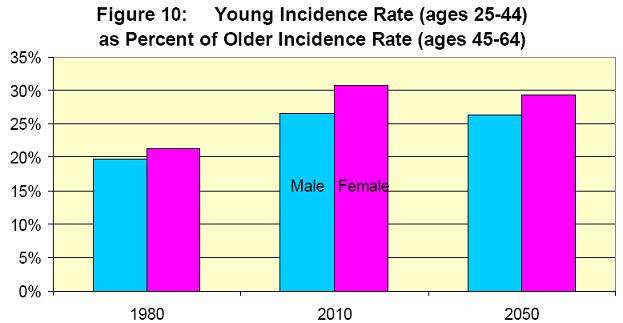

The reason for the rise in male age-sex-adjusted disability prevalence between 1990 and 2010 lies in the age distribution of disability incidence rates. While the overall age-sex-adjusted incidence rate was fairly stable for men, a relative shift toward new disabled-worker awards at younger ages explains the prevalence increase. All else being equal, shifting new disability incidence from ages 45-64 to ages 25-44 will increase the total number of beneficiaries, or prevalence, because the younger awardees may remain disabled for many more years.

The figure below illustrates the degree to which disability incidence rates at ages 25-44 grew relative to incidence rates at ages 45-64, both for men and women, between 1980 and 2010. The shift toward relatively lower ages of disability incidence was even stronger for women than for men. This, combined with the age-sex-adjusted increase in disability incidence for women, largely explains the historical increase in prevalence rates for women.

The shift toward relatively lower ages in disability incidence rates stabilized after 2000. We expect that the relative incidence rates by age will continue to be stable in the future. This, combined with stable age-sex-adjusted overall incidence rates, explains our relatively stable projection of future age-sex-adjusted disability prevalence rates.

While we feel fairly confident about projections for the future, two questions remain about the past: (1) why did disability incidence grow at younger ages relative to older ages; and (2) are there any special characteristics of the additional, younger disabled worker awards?

Due to the complexity of the disability criteria and determination process, and the nature of disability, it is very difficult to determine why incidence rates at younger ages rose from the levels in 1975-1985 to the levels in 2000-2010. However, we can gain some insight into both questions by considering the characteristics of younger versus older disability beneficiaries over time. For example, we can consider (a) relative benefit levels across ages and (b) the distribution of primary diagnosis for younger versus older disabled worker awards.

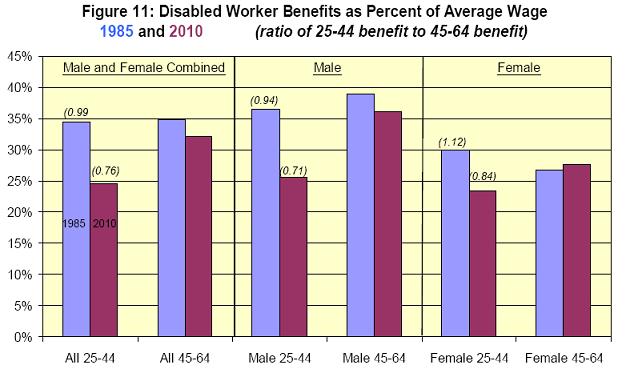

The chart below provides an interesting comparison of benefit levels for younger versus older disabled worker beneficiaries in 1985 and 2010. For each group, the average benefit level is expressed as a percentage of the national average wage index (AWI) for the year.

In 1985, the average benefit level for all younger beneficiaries (age 25-44) was very close to the average benefit level of older beneficiaries (45-64). By 2010, the average benefit level for younger beneficiaries was 24 percent lower than that for older beneficiaries. The change is similar for men and women considered separately. This suggests that the increase in younger disabled worker awards between 1985 and 2010 came from insured workers with low career-average earnings levels, either because they were low paid workers or because they had intermittent employment. The implication for future average benefit levels is also interesting. As the recent younger beneficiaries with low benefit levels age, they will gradually restrain the growth in the average benefit level for older beneficiaries in 2030 and later. Thus, the increase in disability prevalence from younger disabled worker awards will be partly mitigated by lower future benefit levels.

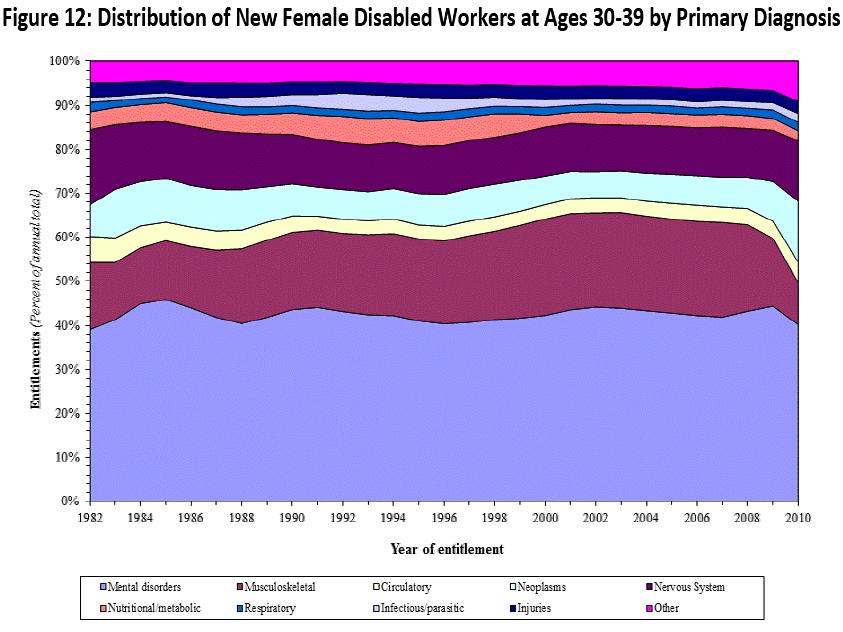

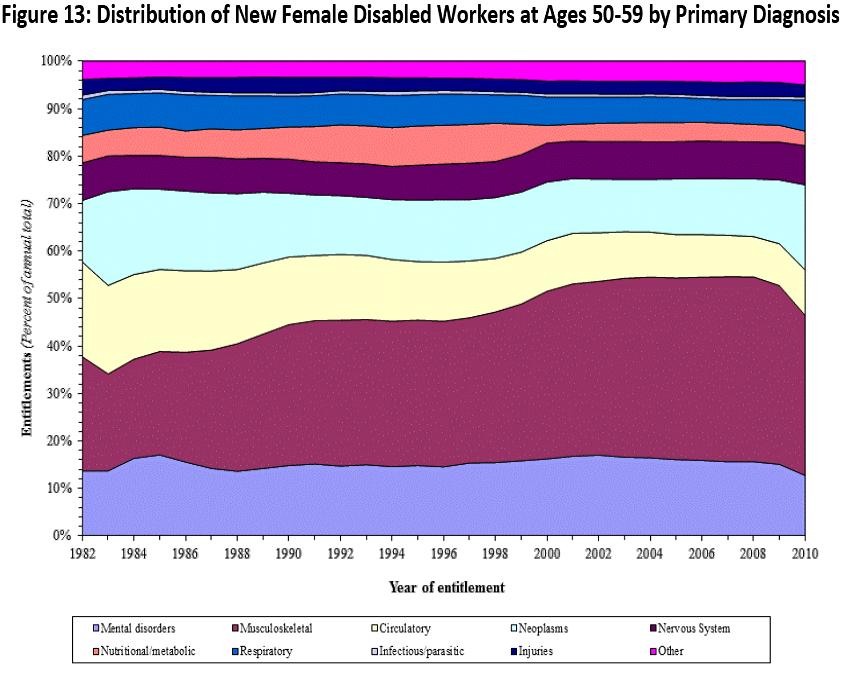

A second characteristic we can consider regarding younger versus older disabled worker beneficiaries is any change in awards by category of medically determinable impairment (primary diagnosis code). The figure below shows that even though the number of female disabled worker awards at younger ages has risen rapidly, the distribution by diagnosis has remained very stable. The pattern for younger men is very similar.

At higher ages, female disabled worker awards show increases in musculoskeletal diagnoses and decreases in circulatory diagnoses. The patterns for males are also similar at these older ages. These effects do not appear to explain the increase in young awards.

Conclusion

Disability insurance is highly complex and challenging to administer. General demographic changes have increased the cost of the DI program over the past 20 years in much the same way that demographics will raise OASI and Medicare costs over the next 20 years. Disability insured rates have increased substantially for women, as have age-sex-adjusted incidence rates for younger insured women, further contributing to higher DI cost. However, all of these trends have stabilized or are expected to do so in the future.

We project that the number of DI beneficiaries will continue to increase in the future, but only at about the rate of increase in workers. Thus, the current shortfall in tax income compared to DI program cost is projected to be stable in the future. Restoring sustainable solvency for the DI program requires about a 16-percent reduction in benefits, a 20-percent increase in revenue, or some combination of these changes. Even if such changes are not effected soon, a modest reallocation of the total OASDI payroll tax can be enacted prior to 2018 that would equalize the actuarial status of the OASI and DI programs, allowing both to pay full scheduled benefits until 2036.