The Development of Social Security in America

Social Security Bulletin, Vol. 70, No. 3, 2010 (released August 2010)

This article examines the historical origins and legislative development of the U.S. Social Security program. Focusing on the contributory social insurance program introduced in title II of the Social Security Act of 1935, the article traces the major amendments to the original program and provides an up-to-date description of the major provisions of the system. The article concludes with a brief overview of the debate over the future of the program, and it provides a summary assessment of the impact and importance of Social Security as a central pillar of the U.S. social welfare system.

Larry DeWitt is a public historian with the Office of Publications and Logistics Management, Social Security Administration.

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank the several reviewers for the Bulletin for their helpful comments and, in particular, Joni Lavery for her assistance with the tables and charts in the article.

Contents of this publication are not copyrighted; any items may be reprinted, but citation of the Social Security Bulletin as the source is requested. The findings and conclusions presented in the Bulletin are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Social Security Administration.

Conceptual Foundations and Historical Precedents

| CES | Committee on Economic Security |

| COLA | cost-of-living adjustment |

| FRA | full retirement age |

| GAO | General Accounting Office (now known as the Government Accountability Office) |

| RET | retirement earnings test |

| SSA | Social Security Administration |

| SSI | Supplemental Security Income |

This section provides a high-level overview of the historical background and developments leading up to the establishment of the Social Security system in the United States.

The Origins of Social Insurance

Economic security is a universal human problem, encompassing the ways in which an individual or a family provides for some assurance of income when an individual is either too old or too disabled to work, when a family breadwinner dies, or when a worker faces involuntary unemployment (in more modern times).

All societies throughout human history have had to come to terms with this problem in some way. The various strategies for addressing this problem rely on a mix of individual and collective efforts. Some strategies are mostly individual (such as accruing savings and investments); others are more collective (such as relying on help from family, fraternal organizations and unions, religious groups, charities, and social welfare programs); and some strategies are a mix of both (such as the use of various forms of insurance to reduce economic risk).

The insurance principle is the strategy of minimizing an individual's economic risk by contributing to a fund from which benefits can be paid when an insured individual suffers a loss (such as a fire that destroys the home). This is private insurance. The modern practice of private insurance dates at least back to the seventeenth century with the founding in 1696 of Lloyds of London. In America, Benjamin Franklin founded one of the earliest insurance companies in 1752. Historically, private insurance was mainly a way that the prosperous protected their assets—principally real property. The idea of insuring against common economic "hazards and vicissitudes of life" (to use President Franklin Roosevelt's phrase) really only arose in the late nineteenth century in the form of social insurance.

Social insurance provides a method for addressing the problem of economic security in the context of modern industrial societies. The concept of social insurance is that individuals contribute to a central fund managed by governments, and this fund is then used to provide income to individuals when they become unable to support themselves through their own labors. Social insurance differs from private insurance in that governments employ elements of social policy beyond strict actuarial principles, with an emphasis on the social adequacy of benefits as well as concerns of strict equity for participants. Thus, in the U.S. Social Security system, for example, benefits are weighted such that those persons with lower past earnings receive a proportionately higher benefit than those with higher earnings; this is one way in which the system provides progressivity in its benefits. Such elements of social policy would generally not be permissible in private insurance plans.

"The year 1920 was a historical tipping-point. For the first time in our nation's history, more people were living in cities than on farms."

Historical Statistics of the United States:

Colonial Times to 1957

The need for social insurance became manifest with the coming of the Industrial Revolution. Earlier forms of economic security reflected the nature of preindustrial societies. In preindustrial America, most people lived on the land (and could thus provide their own subsistence, if little else); they were self-employed as farmers, laborers, or craftsmen, and they lived in extended families that provided the main form of economic security for family members who could not work. For example, in 1880, America was still 72 percent rural and only 28 percent urban. In only 50 years, that portrait changed; in 1930, we were 56 percent urban and only 44 percent rural (Bureau of the Census 1961).1

The problem of economic security in old age was not as pressing in preindustrial America because life expectancy was short. A typical American male born in 1850 had a life expectancy at birth of only 38 years (a female, only 2 years longer).2 But with the dawning of the twentieth century, a revolution in public sanitation, health care, and general living standards produced a growing population of Americans living into old age (see Chart 1).

Growth in U.S. population aged 65 or older, selected years 1870–1940

| Year | Number of persons aged 65 or older |

|---|---|

| 1870 | 1,153,649 |

| 1880 | 1,723,459 |

| 1890 | 2,417,288 |

| 1900 | 3,080,498 |

| 1910 | 3,949,524 |

| 1920 | 4,933,215 |

| 1930 | 6,633,805 |

| 1940 | 9,019,314 |

Thus, the shift from preindustrial to industrialized societies undermined traditional strategies for providing economic security and created a need for new forms of social provision.

Civil War Pensions

The only substantial precedent for federal social insurance was the system of Civil War pensions. The federal government began paying benefits to Union veterans and their surviving families almost from the start of the war (Bureau of the Census 1975).3

In 1893, the peak-cost year, Civil War pensions accounted for 41.5 percent of the federal budget. Not coincidentally, the federal budget that year changed from a surplus of over $2 million in 1892 to a deficit of over $61 million in 1893 (the first deficit since the end of the Civil War).4 (For comparison, the Social Security system was about 22 percent of the federal budget in 2008.)

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Civil War pension system had become a de facto social insurance program—paying retirement, disability, and survivors benefits—albeit for a limited (and vanishing) cohort of the American population.5 Surprisingly, Civil War pension benefits were still being paid until 2003. In that year, the last surviving widow of a Civil War veteran died at age 94.6

The European Models

By the time America adopted its first national social insurance plan in 1935, there were already more than 20 nations around the world with operating social insurance systems (Liu 2001). The first Social Security retirement system was put in place in Germany in 1889. Six years earlier, Germany adopted a workers' compensation program and health insurance for workers. Great Britain instituted disability benefits and health insurance in 1911 and old-age benefits in 1925. These European systems, especially the German system, were to a considerable degree models for the American system. Many of the European systems, however, drew contributions from the government as well as from workers and their employers. This was a precedent America did not adopt.

America on the Eve of Social Security

Because social insurance began in Europe decades before it crossed the Atlantic to our shores, there was time for the development of American expertise on the subject. Among the notable academic experts were Henry Seager, professor at Columbia University, who authored the first American book on social insurance, and Barbara Armstrong, professor at the University of California at Los Angeles (Seager 1910; Armstrong 1932). Two social insurance advocates stand out: Isaac Rubinow and Abraham Epstein (Rubinow 1913 and 1934; A. Epstein 1936; P. Epstein 2006).7

In addition to these advocates for a European style social insurance system, there were related developments at the state level in America before 1935. Wisconsin, for instance, enacted the first workers' compensation program in 1911 and the first state unemployment insurance program in 1934.8

Throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century, there was a concerted movement for Mothers Pensions (the forerunner of what we would come to know as Aid to Families with Dependent Children). The first Mothers Pensions program appeared in 1911; 40 of the 48 states had such programs by 1920. However, the monthly stipends were modest and varied tremendously from state to state—from a high of $69.41 in Massachusetts to a low of $4.33 in Arkansas (Skocpol 1992, 466 and 472).

The state old-age pension movement was the most active form of social welfare before Social Security. This movement was an attempt to persuade state legislatures to adopt needs-based pensions for the elderly. Lobbying for old-age pensions was well organized and was supported by a number of prominent civic organizations, such as the Fraternal Order of Eagles. State welfare pensions for the elderly were practically nonexistent before 1930, but a spurt of pension legislation was passed in the years immediately preceding passage of the Social Security Act, so that 30 states had some form of old-age pension program by 1935. Although old-age pensions were widespread, they were generally inadequate and ineffective. Only about 3 percent of the elderly were actually receiving benefits under these state plans, and the average benefit amount was about 65 cents per day ($19.50 per month).

The Great Depression and Economic Security

Although the Depression that began in 1929 affected virtually everyone in America, the elderly were especially hard hit. Older workers tended to be the first to lose their jobs and the last to be rehired during economically difficult times. In the pre–Social Security era, almost no one had any reliable cash-generating form of retirement security. Fewer than 10 percent of workers in America had any kind of private pension plan through their work. Retirement as an expected and ordinary phase of a life well lived—as we experience it today—was virtually unknown among working class Americans before the arrival of Social Security. The majority of the nonworking elderly lived in some form of economic dependency, lacking sufficient income to be self-supporting.9

This extreme economic climate of the 1930s saw a proliferation of "pension movements," most of which were dubious and almost certainly unworkable. The most well known of these radical pension movements was the Townsend Plan. It promised every American aged 60 or older a retirement benefit of $200 per month—at a time when the average income of working Americans was about $100 a month (Amenta 2006). Huey Long, senator from Louisiana, offered his Share the Wealth plan; Father Charles Coughlin, the radio priest, advanced his Union for Social Justice; and the novelist Upton Sinclair promoted the End Poverty in California plan.10 Millions of desperate seniors joined efforts to make these schemes national policy. As the clamor for old-age pensions rose, President Roosevelt decided that the government needed to come forward with some realistic and workable form of old-age pension. He told Frances Perkins, his secretary of labor, "We have to have it. The Congress can't stand the pressure of the Townsend Plan unless we have a real old-age insurance system…" (Perkins 1946, 294).

However, the Great Depression is not the reason for having a Social Security system; the reason is the problem of economic security in a modern industrialized society. The Depression was the triggering event that finally persuaded Americans to adopt a social insurance system.

Crafting the American Variety of Social Insurance

Historians typically divide the years of the Franklin Roosevelt presidency into a "First New Deal" and a "Second New Deal."11 The First New Deal (1933–1934) was the period of "relief and recovery" from the immediate impacts of the Depression. The Second New Deal (1935–1937) was the period of "reform," in which the administration sought to introduce longer-lasting changes to the nation's political economy. The Social Security Act of 1935 is the defining initiative and starting point of this Second New Deal. It was also President Roosevelt's proudest domestic accomplishment as president (Perkins 1946, 301).

"The one almost all-embracing measure of security is an assured income. A program of economic security…must provide safeguards against all of the hazards leading to destitution and dependency."

Report of the CES to Congress

To craft this unprecedented new form of federal social provision, President Roosevelt appointed a special panel—the Committee on Economic Security (CES)—to study the existing systems around the world, to analyze the problem of economic security in the United States, and to design a social insurance system "suited to American purposes." The CES was chaired by Secretary of Labor Perkins, who was clearly the most important figure in this early pioneering effort (DeWitt 2009).

The CES began its work in June 1934, and by the end of the year, the committee had completed its major studies and designed a legislative proposal, which the president submitted to Congress in January 1935.12

The Social Security Act of 1935: A Cornerstone

The proposed Economic Security Act was submitted to Congress on January 17, 1935.13 Hearings were held in the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Finance Committee throughout January and February. The bill was debated in the two houses for a total of 18 days, and it was signed into law on August 14, 1935.14 The legislation that now is thought of simply as "Social Security" was in fact an omnibus bill containing seven different programs (Table 1).

| Title | Program | Description |

|---|---|---|

| I | Old-Age Assistance | Federal financial support and oversight of state-based welfare programs for the elderly |

| II | Federal Old-Age Benefits | The Social Security program |

| III | Unemployment Insurance | National unemployment insurance, with federal funding and state administration |

| IV | Aid to Dependent Children | State-based welfare for needy children (what would come to be called AFDC) |

| V | Grants to States for Maternal and Child Welfare | Federal funding of state programs for expectant mothers and newborns |

| VI | Public Health Work | Federal funding of state public health programs |

| X | Aid to the Blind | Federal funding of state programs to aid the blind |

| SOURCE: http://www.socialsecurity.gov/history/35actinx.html. | ||

Much of the debate and interest in the Congress concerned the Old-Age Assistance and Unemployment Insurance programs (Titles I and III of the act). Most members of Congress paid scant attention to the Title II program, even though history would prove it to be the most significant provision of the law.

The main debate over the Social Security program involved two issues: (1) the program's financing, in particular, the role of the reserve fund; and (2) the question of whether participation might be made voluntary for certain employers.

On the financing issue, President Roosevelt insisted that the program be self-supporting, in the sense that all of its financing must come from its dedicated payroll taxes and not from general government revenues. He viewed the idea of using general revenues as tantamount to a "blank check" that would allow lawmakers to engage in unbridled spending, and he feared it would inevitably lead to unfunded future deficits. By tying expenditures to a dedicated revenue source, the program could never spend more than it could accrue through payroll taxation.

However, there are a couple of well-known problems with the start-up of all pension schemes. Typically, pension system costs are lowest in the early days when few participants have retired and much higher later on when more people qualify for benefits. Funding a pension system on a current-cost basis thus would impose significantly higher taxes on future cohorts of beneficiaries. To offset this tendency, the CES planners proposed using a large reserve fund that could be used to generate investment income thereby meeting a portion of future program costs. The concept of the Social Security reserve was thus created. Out of an abundance of caution, the reserve fund could only be invested in government securities or "in obligations guaranteed as to both principal and interest by the United States." As enacted, the Social Security Act created a reserve that was then estimated to reach $47 billion by 1980 (DeWitt 2007).15

Congressional opponents of the reserve believed that the reserve was unworkable. These members made two arguments: (1) Congress would spend the money in the reserve for purposes of which opponents might not approve, and (2) the idea of government bonds as a repository of genuine economic value was dubious. Thus, the Republican members of the Ways and Means Committee dissented from passage of the law. Most members of Congress, however, gave no indication of sharing these concerns, and the law was adopted with an overwhelmingly bipartisan vote in both houses of Congress (DeWitt, Béland, and Berkowitz 2008, 527).

The second problem with the start-up of pension systems is that early program participants do not typically have the opportunity to work long enough to qualify for an adequate benefit amount—if their benefit is computed on strictly actuarial grounds. Therefore, most pension systems (in both the government and private sectors) usually make some special allowance in the form of a subsidy to early participants. Benefits to the earliest cohorts of Social Security beneficiaries were in fact subsidized in this way.

This kind of subsidy is a foundational principle of the Social Security system: Benefits should be both adequate and equitable. "Adequate" means that the benefits should be generous enough to provide real economic security to the beneficiaries; "equitable" means that the benefits should be related in some way to the level of contributions that a participant has made to the system (for example, higher contributions should result in higher benefits). Some policies seek to address the adequacy factor of this principle, and others seek to address the program's equity; policymaking in Social Security is often a question of seeking the best balance between these two factors.

"This law, too, represents a cornerstone in a structure which is being built but is by no means complete."

President Roosevelt on signing the 1935 Act

The issue regarding voluntary participation focused on those few establishments that had existing company pension programs. An amendment introduced by Senator Clark (D-MO) proposed that any firm having a plan that was at least as generous as the proposed government plan be allowed to opt out of participation. This issue held up the bill for a month as the conference between the two houses was stymied by the Clark amendment. Finally, the sponsors of the amendment dropped the provision and the bill went to the president for his signature.16

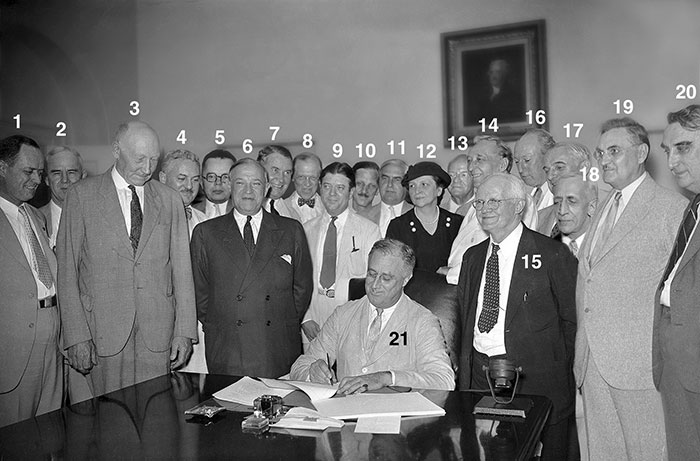

The illustration below is a composite photograph constructed from several of the images taken at the signing ceremony.

SSA History Museum & Archives.

The original program was designed to pay retirement benefits only at age 65 and only to the covered worker, himself or herself. The selection of age 65 was a pragmatic "rule-of-thumb" decision based on two factors. First, about half of the state old-age pension systems then in operation in the United States used age 65. Second, the CES actuaries performed calculations with various ages to determine the cost impacts of setting the retirement age at various levels, and age 65 provided a reasonable actuarial balance in the system. (In 1935, remaining life expectancy at age 65 was approximately 12 years for men and 14 years for women.)17

There was an "absolute" retirement test for receipt of benefits, based on the social insurance principle that benefits were a partial replacement of wages lost because of the cessation of work. Thus, for any month in which a beneficiary worked and earned any amount of money whatsoever, he or she was ineligible for a Social Security retirement benefit for that month.

Benefits were computed based on the total cumulative wages that a worker had in covered employment. Thus, the more years in covered employment, the higher the eventual benefit amount (other things being equal). The benefit formula also contained the "social weighting" (or progressivity) aspect that persists to this day, in which workers with lower earnings levels receive a proportionately higher benefit, relative to their prior earnings, than workers with high wages. This process addresses the adequacy half of the equity/adequacy dyad, and it is one way in which social insurance diverges from private insurance.

Coverage was quite limited. Slightly more than half the workers in the economy were participants in the original program. Coverage under the program was by occupational category, with most covered workers employed in "commerce and industry." Among the excluded groups were the self-employed, government employees, persons already age 65, the military, professionals (doctors, lawyers, etc.), employees of nonprofit organizations, and agricultural and domestic workers.18

Financing was to be generated from a payroll tax imposed equally on employers and employees (with no government contribution). The tax rate was initially set at 1 percent on each party, with scheduled increases every 3 years, to an eventual rate of 3 percent each by 1949. Payroll taxes were to begin in January 1937, and the first benefits were to be payable for January 1942. The wage base (the amount of earnings subject to the tax) was set at $3,000. This level was sufficient to include 92 percent of all wages paid to the covered groups. Stated another way, about 97 percent of all covered workers had their entire earnings subject to the tax (SSA 2010).19

Building on the Cornerstone

The Social Security system with which we are familiar today is far different from the one created in 1935. In each of the three major policymaking areas (coverage, benefits, and financing), the program has undergone a slow but dramatic evolution.

Coverage was initially very limited. Only slightly more than half the workers in the economy were participants in the program under the 1935 law. Today we could describe Social Security's coverage as nearly universal, with about 93 percent of all workers participating in the program. Benefits were initially paid only to retirees and only to the individual worker, himself or herself. There were no other types of benefits and no benefits for dependent family members. Benefits were also far from generous. Financing has always been an issue. Although some aspects of this matter were decisively settled in 1935, others have continued to be sources of ongoing policy contention and political debate. Social Security has evolved over the past 75 years principally through the form of a dozen or so major legislative enactments. In broad terms, the period from 1935 through 1972 is the expansionary period for the program, and the period since 1972 has been a period of policy retrenchment.20 The major Social Security legislation is highlighted in Table 2.21

| Law | Date enacted | Major features |

|---|---|---|

| The Social Security Act | August 14, 1935 | Established individual retirement benefits. |

| The 1939 amendments | August 10, 1939 | Added dependents and survivors benefits and made benefits more generous for early participants. Financing at issue. |

| The 1950 amendments | August 28, 1950 | Adjusted, on a major scale, coverage and financing. Increased benefits for the first time. Provided for gratuitous wage credits for military service. |

| Legislation in 1952 | July 18, 1952 | Raised benefits; liberalized retirement test and expanded gratuitous wage credits for military service. |

| Legislation in 1954 | September 1, 1954 | Extended coverage. Disability "freeze." |

| The 1956 amendments | August 1, 1956 | Added cash disability benefits at age 50. Early retirement for women. |

| The 1958 amendments | August 28, 1958 | Added benefits for dependents of disabled beneficiaries. |

| The 1960 amendments | September 13, 1960 | Disability benefits at any age. |

| The 1961 amendments | June 30, 1961 | Established early retirement for men. Liberalized eligibility requirements for other categories. |

| The 1967 amendments | January 2, 1968 | Added disabled widow(er)s benefits. |

| The 1972 Debt-Ceiling Bill | July 1, 1972 | Added automatic annual cost-of-living adjustments. |

| The 1977 amendments | December 20, 1977 | Raised taxes and scaled back benefits. Long-range solvency at issue. |

| The 1980 amendments | June 9, 1980 | Tightened disability eligibility rules. |

| Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981 | August 13, 1981 | Eliminated student benefits after high school. |

| The 1983 amendments | April 20, 1983 | Raised taxes and scaled back benefits. Long-range and short-range solvency at issue. |

| Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 | August 10, 1993 | Raised taxable portion of Social Security benefits from 50 percent to 85 percent. |

| Senior Citizens Freedom to Work Act of 2000 | April 7, 2000 | Eliminated the retirement earnings test for those at the full retirement age. |

| SOURCE: Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report RL30920, Major Decisions in the House and Senate on Social Security, 1935–2009. | ||

The First Social Security Payments

The Social Security Act of 1935 set the start payroll taxes in 1937 and the start of monthly benefits in 1942. This was a kind of "vesting period," in which a minimum amount of work would be required to qualify for monthly benefits. This period also allowed time to build some level of reserves in the program's account before payments began flowing to beneficiaries.

The vesting period arrangement presented a conundrum: How should the program treat those workers who turn age 65 during this period, or who die before January 1942? These individuals would have contributed something to the system, and it was thought that they should receive some return for their contributions. Thus, the original program paid two types of one-time, lump-sum benefits in the 1937–1939 period. A person attaining age 65 during this time would be entitled to a one-time payment equal to 3.5 percent of his or her covered earnings; and the estate of a deceased worker would receive a "death benefit" computed in the same way. Because the payroll tax in these years was only 1 percent for workers, this would mean a substantial "return" on their payroll taxes.

The first person to take advantage of these benefits—and thus the first Social Security payment ever made—was a Cleveland, Ohio streetcar motorman named Ernest Ackerman. Ackerman worked one day under Social Security—January 1, 1937. His wage for that day was $5. He dutifully paid his payroll tax of one nickel and he received a one-time check from Social Security for 17 cents.22

In the 1937–1939 period, more than 441,000 people received Social Security benefits totaling over $25 million (see Table 3). Of the total monies paid to beneficiaries during this period, 39 percent was for so-called "life cases" (like Ackerman), and 61 percent went for "death benefits."

| Year | Beneficiaries | Payments ($ in millions) |

|---|---|---|

| 1937 | 53,236 | 1,278,000 |

| 1938 | 213,670 | 10,478,000 |

| 1939 | 174,839 | 13,896,000 |

| Total | 441,745 | 25,652,000 |

| SOURCE: SSA (1940, Table 5, p. 47 and Table 15, p. 34). | ||

The Amendments of 1939

Even before monthly benefits were due to start in 1942, the Social Security Act of 1935 was changed in quite fundamental ways by major legislative amendments in 1939. This legislation emerged from the work of an advisory council jointly formed in 1938 by the Senate Finance Committee and the Social Security Board. Conservative members of the Finance Committee (especially Arthur Vandenberg, R-MI) wanted to use the council to revisit the debate over the reserve, while the Social Security Board (especially Arthur Altmeyer, its chairman) wanted to use the council to promote expansion of the benefits beyond the basic individual retirement program codified in the 1935 act. In the end, both groups got some of what they wanted. The legislation advanced the start of monthly benefits from 1942 to 1940; it added dependents benefits; and it replaced the system of one-time death payments with regular monthly survivors benefits.

Advancing the start of monthly benefits from 1942 to 1940 meant that the first Social Security monthly benefit would be paid in January 1940. By chance, the first person to become a monthly Social Security beneficiary was a retired legal secretary from Ludlow, Vermont—Ida May Fuller. Fuller retired in November 1939 at age 65 and received the first-ever monthly Social Security benefit on January 31, 1940. Her monthly check was for $22.54.

The amendments of 1939 provided benefits for wives and widows (but no corresponding benefits for men) and also for dependent children. The wife of a retired worker and each minor child could receive a benefit equal to half the covered worker's benefit, and widows could receive 75 percent of the worker's benefit (all for no additional payroll taxes).23

This was a major expansion of the program. Indeed, one might well say that this was the "second start" of Social Security in America. The 1939 legislation changed the basic nature of the program from that of a retirement program for an individual worker, to a family-based social insurance system (based on the then-current model of the family, in which the man was the breadwinner with a nonworking wife who cared for the minor children).

The 1939 law also made benefits to early program participants significantly higher than under the original law, although benefits were lowered for later participants. And it made benefits for married couples higher than those for single workers, by virtue of the addition of dependents benefits. In addition, benefits for single workers were lowered somewhat from their 1935 values. Thus, early program participants and married couples benefited from the changes in 1939, while single persons and later participants had their benefits reduced. This combination of policy changes was a principal way in which the actuarial balance of the system was to be maintained.

These policies considerably increased the cost of the program in the near term. This pleased the opponents of the large reserve because it immediately reduced the size of the reserve. It was claimed that in the long run the changes were revenue neutral, and thus it is unclear what real change the amendments made in the long-range financing of the system. However, this claim for revenue neutrality was not well documented at the time, and it has now come under considerable doubt (DeWitt 2007).

The 1939 legislation also introduced the trust fund for the first time as a formal legal device to serve as the asset repository for Social Security surpluses. (Under the 1935 law, Social Security's funds were more literally a bookkeeping entry in the Treasury Department's general accounts.)

A smaller, but important, change was also introduced in 1939. Under the 1935 law, benefits were computed based on the total cumulative wages a worker had under covered employment. Thus, a long-time covered worker would receive a higher monthly benefit than one who worked less time under the program—even if they both had the same level of wages. So, for example, if "worker A" worked 20 years under Social Security and earned $20,000 a year and "worker B" worked 30 years at $20,000 a year, worker B would receive a higher benefit because his or her cumulative wages would be greater than that of the other worker—even though they were both earning $20,000 a year.24

As part of the refinancing in the amendments of 1939, benefits were shifted from this cumulative basis to that of average monthly wages. One effect of this change would be that everyone who had the same average monthly wage would receive the same benefit amount, regardless of how many years they were covered under Social Security. The intent here was to make benefits more adequate by insuring that persons with the same earnings level would receive the same benefit. (Keep in mind that in these early years, the benefits were still viewed as replacement of income lost because of cessation of work. So the idea is that persons earning at a given level need the same level of income replacement, regardless of how long they have been covered by the program.) However, to maintain some equity for long-time program participants, a 1 percent increment was added to the benefit formula for each year of program participation. Thus, a long-time participant would still receive a higher monthly benefit than a short-time one, even if they both earned the same average wages. (Here again, we see the attempt to balance adequacy and equity.)

The 1939 legislation also introduced the first modification of the retirement test. Under this relaxed provision, a retirement benefit was payable for any month in which the beneficiary earned less than $15 (any earnings over this limit produced a zero benefit for that month). This was the beginning of a gradual erosion of the requirement that a beneficiary be fully retired to receive a retirement benefit, a process that would culminate in the elimination of the retirement earnings test (RET) in 2000 for those at or above the full retirement age (FRA).

The 1940s: A Decade of Start/Stop Tax Policy

The decade of the 1940s was in most respects a quiescent period for Social Security policymaking: No new categories of benefits were added, no significant expansions of coverage occurred, the value of benefits was not increased (there were no cost-of-living adjustments (COLAs) in these early days), and the tax rates were not raised during the entire decade.25 This last nonevent (no tax rate increase) was, however, a significant anomaly.

The 1935 law set a schedule of tax increases beginning in 1939. Tax rates were scheduled to rise four times between 1935 and 1950. These periodic increases were necessary in order to meet President Roosevelt's demand that the system be self-supporting, and they were the basis on which the actuarial estimates were derived. However, as part of the trade-offs in the amendments of 1939, the first rate increase (in 1940) was cancelled. Then with the coming of World War II, the program's finances were dramatically altered. With virtually full employment in the wartime economy, more payroll taxes began flowing into the system than the actuaries originally anticipated, and retirement claims dropped significantly. The net result was that the trust fund began running a higher balance than was previously projected. This led to the Congress enacting a series of tax rate "freezes," which voided the tax schedule in the law. Each time a new tax rate approached, the Congress would void the increase with the expectation that the normal schedule would resume at the next step in the schedule—but this expectation was never met.

In all, eight separate legislative acts froze taxes at their 1935 level all the way to 1950 (see Table 4). The result of these rate freezes was unclear at the time (the Congress focused only on the short-run consequences), but it is probable that the effect of these taxing policies produced the first long-range actuarial deficits in the program (DeWitt 2007).

| Year | 1935 law | Actual rates |

|---|---|---|

| 1937 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 1938 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 1939 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| 1940 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| 1941 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| 1942 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| 1943 | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| 1944 | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| 1945 | 4.0 | 2.0 |

| 1946 | 5.0 | 2.0 |

| 1947 | 5.0 | 2.0 |

| 1948 | 5.0 | 2.0 |

| 1949 | 6.0 | 2.0 |

| 1950 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| SOURCE: Author's compilation. | ||

The Amendments of 1950

There were three particular features of the program before 1950 that were the source of discontent among advocates and beneficiaries: (1) the program had no provision for periodic benefit increases, (2) benefit levels overall were quite low, and (3) the program only covered about half the workers in the economy. There was also continuing debate over the size and role of the trust fund and the long-range status of the program's finances.

The low level of benefits was of particular concern. Even by 1950, the average state old-age welfare benefit was higher than the average Social Security retirement benefit, and the number of persons receiving welfare-type, old-age benefits was greater than the number receiving Social Security retirement benefits. (The average Social Security retirement benefit at the end of 1947 was only $25 per month for a single person (DeWitt, Béland, and Berkowitz (2008, 162).)

Moreover, because the law made no provision for any kind of benefit increases, whatever amount beneficiaries were awarded in their first monthly payment was the benefit they could expect for the rest of their lives. So, for example, Ida May Fuller (discussed earlier) lived to be 100 years old and thus collected checks for 35 years. Imagine, then, the effect of 35 years of inflation on the purchasing power of her $22.54 benefit.

The 1950 legislation (like the 1939 legislation) emerged out of the recommendations of an advisory council.26 The most dramatic provision in the new law raised the level of Social Security benefits for all beneficiaries an average of 77 percent. Although this was not, strictly speaking, a COLA (but rather an effort to raise the overall level of benefits), it did establish a precedent for the idea that benefits should be raised periodically. However, the precedent also meant that benefits were not raised automatically, but only when a special act of Congress was undertaken to do so. Thus, for many years afterwards, benefit increases would remain spotty, until automatic COLAs began in 1975.

The match between the pre-1975 benefit increases and the actual rate of inflation was far from perfect. In some years, benefits were increased more than inflation, and in other years they were increased less, or not at all. This mismatch was particularly large in the run-up to automatic COLAs in the early 1970s. In 1972, for example, benefits were increased by 20 percent, while inflation had only risen by 1.3 percent from the year before. Cumulatively, during this period, benefits increased 391 percent, while inflation only increased 252 percent from 1940 through 1974 (see Table 5).

| Calendar year | Increase in benefits | Actual increase in inflation a |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Base year | . . . |

| 1941 | None | 5 |

| 1942 | None | 11 |

| 1943 | None | 6 |

| 1944 | None | 2 |

| 1945 | None | 2 |

| 1946 | None | 8 |

| 1947 | None | 14 |

| 1948 | None | 8 |

| 1949 | None | -1 |

| 1950 | 77.0 | 1 |

| 1951 | None | 8 |

| 1952 | 12.5 | 2 |

| 1953 | None | 1 |

| 1954 | 13.0 | 1 |

| 1955 | None | 0 |

| 1956 | None | 1 |

| 1957 | None | 3 |

| 1958 | None | 3 |

| 1959 | 7.0 | 1 |

| 1960 | None | 2 |

| 1961 | None | 1 |

| 1962 | None | 1 |

| 1963 | None | 1 |

| 1964 | None | 1 |

| 1965 | 7.0 | 2 |

| 1966 | None | 3 |

| 1967 | None | 3 |

| 1968 | 13.0 | 4 |

| 1969 | None | 5 |

| 1970 | 15.0 | 6 |

| 1971 | 10.0 | 4 |

| 1972 | 20.0 | 3 |

| 1973 | None | 6 |

| 1974 | 11.0 | 11 |

| 1940–1974 b | 391.0 | 252 |

| SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics data. Calculations by the author. | ||

| NOTE: . . . = not applicable. | ||

| a. Based on Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers, nonseasonally adjusted annual averages. | ||

| b. Cumulative averages. | ||

The question of the program's coverage of occupational categories was also of central concern in the 1950 legislation. Up to this point, coverage had not changed significantly since 1935, and at least two-fifths of the workers in the economy were still excluded from the program. The Social Security Advisory Council explicitly recommended that the Congress adopt the goal of universal coverage, stating "The basic protection afforded by the contributory social insurance system under the Social Security Act should be available to all who are dependent on income from work."27

The Congress adopted a large part of the council's recommendation, bringing 10 million additional workers under coverage. The main groups brought under coverage were most self-employed workers and domestic and agricultural workers. Employees of state and local governments were given the option of voluntary coverage, as were employees of nonprofit institutions (subject to certain conditions).

The coverage rules, however, were complex and marked the beginning of a policymaking process for coverage that involved complicated special rules for various occupational groups.28 Nevertheless, we could say that in the amendments of 1950, the program was put on a glide path toward universal coverage (see Chart 2).

Growth in Social Security coverage, selected years 1935–2007

| Year | Percent of civilian workers covered by Social Security |

|---|---|

| 1935 | 45.00 |

| 1939 | 55.10 |

| 1940 | 55.00 |

| 1944 | 60.20 |

| 1945 | 60.00 |

| 1949 | 60.50 |

| 1950 | 60.00 |

| 1955 | 83.00 |

| 1960 | 86.20 |

| 1965 | 87.60 |

| 1970 | 89.90 |

| 1975 | 90.60 |

| 1980 | 90.00 |

| 1985 | 92.90 |

| 1990 | 94.80 |

| 1995 | 94.50 |

| 2000 | 94.40 |

| 2007 | 93.60 |

The 1950 legislation also addressed the issue of the program's financing. Tax rates were increased for the first time, and the program's long-range solvency was assessed; the financing was set such that the program could be certified by the actuaries as being in long-range actuarial balance.29 This part of the legislation effectively ended the debate over the role of the reserve, and it established the precedent that major changes to the program must be assessed for their long-range impact on program financing (DeWitt 2007).

"It may be no exaggeration to say that the 1950 Amendments really saved the concept of contributory social insurance in this country."

Robert M. Ball

The role of the 1 percent "increment" introduced in 1939 was to insure that long-time program participants would receive proportionately higher benefits than workers who just barely met the coverage requirements. However, as part of the financing adjustments of 1950, the increment was eliminated to pay for a portion of the increase in benefit levels. (That is, future benefits were lowered for long-time participants so that benefits could be increased immediately.)

Up to this time, members of the military were not covered by Social Security and therefore did not pay Social Security taxes (and could not earn credits toward an eventual benefit). The 1950 law introduced the principle of gratuitous wage credits for military service—which was treated as covered work, even though no payroll taxes were assessed to finance the credits. The combination of these changes was so significant that the 1950 law has traditionally been known within Social Security policy as the "new start" to the program.30

1952 and 1954: Small Policy Adjustments and Steady Program Growth

The amendments of 1952 raised benefits by 12.5 percent, surprisingly soon after the major boost of 1950. They also raised the "earnings test" limits by 50 percent and expanded the gratuitous wage credits for military service.

The 1954 amendments produced a major expansion of coverage—bringing an additional 10 million workers into the system. This law extended coverage to most remaining uncovered farm workers, self-employed professionals, and state and local government employees (on a voluntary group basis). Benefits were also increased an additional 13 percent.

Perhaps the most significant change in 1952 was one that did not happen. Much of the debate over the legislation concerned a proposal for a "disability freeze." The idea here is to eliminate from the computation of a worker's benefit any years in which the worker had little or no earnings because he or she was disabled. Including years of little or no earnings effectively lowers any eventual retirement benefits, or, in certain cases, prevents the worker from achieving insured status at all. The "freeze" was thus designed to prevent these adverse impacts on retirement benefits. Because federal involvement in any aspect of disability policy was strongly opposed by key interest groups, the Congress ultimately enacted an unusual statute that created a freeze, but which had an expiration date before its effective date. Even so, it was an acknowledgment—at least in principle—of the policy logic of a disability freeze, which would subsequently be enacted 2 years later in the amendments of 1954.

Disability—unlike the attainment of retirement age or the death of a wage-earner—inevitably involves some degree of judgment in assessing eligibility. It is difficult to determine whether someone is too disabled to work, and hence it is possible that unqualified individuals might become eligible for these benefits. This problem of the inherent difficulty in making a disability determination was part of a concern about whether the costs of such coverage can be meaningfully predicted and controlled. Concerns over the potential costs of disability coverage slowed the addition of these benefits in Social Security.31

What is most significant about the disability freeze—from an administrative perspective—is that it required the same process for making a disability determination as would be required for determining eligibility for cash disability benefits. Thus, the entire bureaucratic apparatus and the basic policy structure of a disability program were all put in place starting in 1954, even though we think of disability benefits as having arrived in 1956.

The Coming of Disability Benefits

The freeze legislation of 1954 paved the way for the introduction of cash benefits in 1956 (and provided some degree of reassurance that the administrative challenges of a disability program were manageable). Even so, there was significant disagreement regarding disability benefits and whether they should be added to the program. The legislation was in fact adopted by what was, in effect, a single vote in the Congress (DeWitt, Béland, and Berkowitz 2008, 14–15).

The initial disability program was limited in scope (reflecting the worries about costs). It paid benefits only to those insured workers aged 50–64 and offered nothing for the dependents of those workers. And the law introduced a special type of insured-status rule for disability: fully insured, with 20 out of the last 40 quarters worked, and currently insured, with 6 out of the last 13 quarters worked).32 There was a 6-month waiting period before benefits could be paid, and there was no retroactivity. To fully fund the new benefits, tax rates were raised a combined 0.5 percentage points, and a separate disability trust fund was created.

Disability benefits were liberalized in 1958 by extending them to the dependents of a disabled worker, eliminating the currently insured rule, and permitting up to 12 months of retroactivity with an application. These benefits were liberalized again in 1960 by extending the primary benefit to disabled workers of any age. This quick liberalization was due to the disability program not being as problematic as some had expected.

In addition to creating the disability program, the 1956 legislation contained additional policy changes.

- Coverage was expanded to members of the military, to previously excluded self-employed professionals, and, optionally, to police and firefighters in state or local retirement systems.

- Early retirement at age 62 was made available to women (but not men); special rules were adopted permitting women to become insured with fewer quarters of coverage than men, allowing women to average their earnings over a shorter period than men in order to increase their benefit amount.

The 1960s: Small Policy Adjustments and Steady Program Growth

In addition to the disability liberalization, in 1960 the children's survivor benefit was raised from 50 percent to 75 percent of the workers primary insurance amount. In 1961, men were granted the option of early retirement, insured status and RET rules were relaxed, and the minimum benefit was increased by 21 percent.

The amendments of 1965 (which created the Medicare program) also liberalized the definition of disability by changing the original definition from "of long continued and indefinite duration" to "12 months or longer or expected to result in death." This legislation also lowered the eligibility age for widows from 62 to 60, extended children's benefits to age 21 if a full-time student, provided benefits to divorced wives and widows if they had been married at least 20 years, and reduced the insured-status requirements for persons attaining age 72 before 1969.

Legislation in 1966 granted eligibility to the special age-72 class, even if they had never contributed to Social Security. (These were known as "Prouty benefits," named after the Senator who introduced the provision, Winston Lewis Prouty, R-VT.)

The 1967 amendments provided disabled widows and disabled (dependent) widowers benefits at age 50. On one hand, the definition of disability was tightened to stipulate that disability meant the inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity existing in the national economy, and not just in the local area. (This was consistent with original congressional intent, which had been broadened by court decisions.) On the other hand, the insured-status requirement for disabled workers aged 31 or younger was relaxed. Additional gratuitous wage credits were granted to the military, and ministers were brought into coverage, unless they opted out on grounds of conscience or religious principles.

Financing During the 1950s and 1960s

From the end of World War II up until the early 1970s, overall wages in the economy tended to increase about 2 percent per year above prices. This natural wage growth meant that, other things being equal, the Social Security system would see additional income because of these higher wage levels. However, the actuarial estimates used in Social Security were based on an assumption of static wage and price levels because there were no automatic adjustments in the program for either benefit increases that were due to inflation or increases in the wage base as a result of economic growth. Because both benefit increases and changes in the wage base were the result of irregular congressional actions, the actuaries used current law as the basis for their projections.

But, because wages did in fact grow faster than prices—and because price adjustments were irregular—from time to time the Congress would find itself in the happy position of having more money in the program than had been projected in previous actuarial estimates. Thus, it became possible to increase benefits without fully commensurate increases in tax rates or the wage base. (These increases were sometimes coupled with expansions of coverage, which paid part of the costs associated with the benefit increases.) This process was employed several times during the two-decade period from 1950 through 1960, as shown in Table 6.

| Year | Benefit increases (%) | Tax rate a (%) | Wage base ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1952 | 12.50 | Unchanged | Unchanged |

| 1954 | 13.00 | + 0.5 (each) | Unchanged |

| 1959 | 7.00 | + 0.25 (each) | + 600 (annual) |

| 1965 | 7.00 | Unchanged b | Unchanged b |

| 1968 | 13.00 | -0.10 | + 1,200 (annual) |

| 1970 | 15.00 | Unchanged | Unchanged |

| 1971 | 10.00 | 0.40 | Unchanged |

| 1972 | 20.00 | Unchanged | + 1,200 (annual) |

| SOURCE: SSA (2010, Table 2.A3, pp. 2.4–2.5). | |||

| a. Does not include Medicare or self-employment tax rates. | |||

| b. Rate was unchanged in 1965, but was increased 0.2 percent in 1966, and the wage base was raised $1,800 as part of same legislation. | |||

The Amendments of 1972: The Last Major Expansion

There were two major bills enacted in 1972, which together, greatly expanded the program; this legislation marked the approximate end of the expansionary period in Social Security policymaking.

The first was a simple bill to raise the limit on the national debt. In the Senate, a rider was attached to the debt-limit bill creating the automatic annual COLA procedure beginning in 1975. This was a huge policy change that was adopted in a surprisingly casual manner, although it had been debated for several years, and the Nixon administration was in support of the idea (DeWitt, Béland, and Berkowitz (2008, 267–281). The fact that Social Security benefits are raised whenever there is price inflation in the economy is a major aspect of their value and is a significant contributor to overall program costs. Not only was an "automatic" mechanism introduced to raise benefits along with prices, but the wage base and the annual exempt amounts under the RET were also put on an automatic basis, tied to the rise in average wages (also beginning in 1975).

Subsequent legislation in late 1972 provided additional expansions of the program, which included introducing delayed retirement credits to raise the benefits of workers who postponed filing for Social Security, a new special minimum benefit for workers with low lifetime earnings, benefits for dependent grandchildren, benefits to widowers at age 60, Medicare coverage after 2 years of receiving disability benefits, a reduced disability waiting period from 6 to 5 months, and disability benefits for children disabled before attaining age 22. (The legislation also created the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program.)

The 1977 Amendments: The Beginning of Retrenchment

By the mid-1970s, there were serious financing problems evident in the Social Security program. This was due principally to the adverse economic conditions of the mid-1970s ("stagflation"). The Social Security actuaries reported in 1973 that for the first time, the program was no longer in long-range actuarial balance, and there were difficulties projected in the near term as well. In fact, during the 1975–1981 period, the program was in annual deficit, and assets of the trust funds had to be redeemed to make up the shortfalls.33 The projected long-range deficits would continue for a decade (until the major legislation of 1983).34

Moreover, a major flaw was present in the 1972 legislation that created the "automatics" for price and wage adjustments. This technical flaw had the effect of greatly inflating benefits far beyond the intent of Congress and the traditional expected rates of income replacement. This too had to be addressed in the 1977 legislation. The 1977 amendments were principally targeted toward the issue of program financing.

To correct the indexing error, the adjustments for prices and wages were "decoupled" (DeWitt, Béland, and Berkowitz 2008, 285–287 and 298–323). The practical effect of decoupling was to lower benefits, and the change was applied only to new beneficiaries. To further soften the impact of this reduction, the Congress devised a 5-year phase-in period, during which time benefits were gradually reduced such that they would be at the proper level for those beneficiaries retiring 5 years from the effective date of the decoupling. This attempt at "softening the blow" backfired as those in the phase-down group saw themselves as victims of an unfair "notch" in benefits.35

In addition to the decoupling, the 1977 legislation further addressed the financing issue with a combination of tax increases and benefit reductions. On the revenue side, the law set up a schedule of rate increases such that by 1990, the tax rate would be 6.2 percent (this is still the current rate). Also the wage base was increased in an ad hoc manner beyond the increases authorized in the 1972 law (a total increase of $12,000 in three steps). The automatic provision would then start again from this higher wage base.

On the benefit side, there were three additional provisions reducing benefits: (1) the initial minimum benefit was frozen at $122 per month, (2) benefits for spouses and surviving spouses were offset by an amount related to any government pension that spouses received based on their own work not covered by Social Security (the Government Pension Offset), and (3) the RET was shifted from a monthly to an annual basis.

Also on the benefit side, there were three provisions increasing benefits: (1) the exempt amount under the RET was increased in an ad hoc adjustment by raising it for 5 years for those retirees aged 65 or older, (2) the duration of marriage requirement for divorced and surviving divorced spouses was cut in half—from 20 years to 10, and (3) the value of delayed retirement credits was increased.

The net savings from these changes (expressed as a percent of payroll)36 follow:

- Decoupling: + 4.79 percent of payroll

- Additional benefit changes: + 0.18 percent of payroll

- Tax changes: + 1.78 percent of payroll

In other words, 26 percent of the savings came from tax increases and 74 percent from benefit cuts. The impact on overall financing was to reduce the long-range deficit from 8.20 percent of payroll to 1.46 percent of payroll (SSA 1977). The amendments were said to have restored solvency to the program for the next 50 years, rather than the full 75 years that had traditionally been used as the projection period. Clearly, the long-term financing issues had not been fully resolved by the 1977 legislation.

The Disability Legislation of the 1980s

The Disability Insurance program came under renewed scrutiny during the first half of the 1980s. Throughout the 1970s, disability incidence rates were steadily rising. This led to concern in the Congress and in the Carter administration that disability costs were soaring out of control.

Around the same time, the General Accounting Office (GAO 1978) conducted a very small study of disabled SSI recipients and found that perhaps as many as 24 percent were no longer disabled. An internal study by the Social Security Administration (SSA 1981) found that about 18 percent of the expenditures for the Social Security disability program was being paid to beneficiaries who were no longer disabled (DeWitt, Béland, and Berkowitz 2008, 369–374).37 Thus, in 1980, major disability legislation was enacted in an effort to control costs in the program, to review those already receiving benefits, and to remove those who no longer qualified as disabled. The legislation mandated that the reviews begin by January 1982, and it projected savings from the reviews of about $10 million over 5 years. A follow-up study by GAO (1981) sampled Social Security disability beneficiaries and suggested that as many as 20 percent were no longer disabled, costing the program $2 billion a year.

Upon taking office in early 1981, the Reagan administration decided to accelerate the review process, as this was now projected to be a significant source of budget savings. The reviews began in July 1981 and rather quickly ran into serious political controversy and to public outcries in opposition to the reviews.38 Among other problems, the reviews required only an examination of existing medical records, not face-to-face contact with the beneficiary. This led to isolated instances of obviously disabled individuals having their benefits stopped—incidents that were given wide publicity in the media. Also, the initial round of reviews was targeted to those classes of beneficiaries most likely to have recovered. This seemingly sensible idea led to much higher initial cessation rates than Congress or the public expected, which led in turn to charges that SSA was engaging in a wholesale "purge" of disability beneficiaries.39

SSA also adopted a number of policy positions in the reviews that proved highly problematic. For example, cessations were processed without requiring proof of medical improvement.40 Also, when faced with multiple nonsevere impairments, SSA did not consider the combined effect of the impairments.41 Massive litigation ensued in the federal courts, virtually swamping the court system.42 These lawsuits led to decisions overturning various SSA policies, which prompted the agency to adopt a very controversial practice of issuing formal rulings of "nonacquiescence" with certain court decisions.43 Because of their opposition to SSA's policies, the governors of nine states (comprising 28 percent of the national workload) issued executive orders stopping their state agencies from processing any disability review cases.44

The controversies around the disability reviews became so great that the Congress enacted the Disability Benefits Reform Act of 1984 to restrain the activities set in motion by the 1980 legislation. Key provisions of the act, as highlighted in Collins and Erfle (1985), follow:

- A finding of medical improvement (or other related changes) was necessary to cease disability benefits;

- The combined effect of multiple nonsevere impairments must be considered in disability determinations;

- SSA was required to promulgate new mental impairment rules, reopen all cases of prior cessations involving mental impairments, and reevaluate them under the revised rules;

- SSA was given explicit authority to federalize any state agency making Social Security disability decisions that refused to comply with federal regulations; and

- A "sense of Congress" was expressed stating that nonacquiescence was an invalid legal posture, and if SSA elected to continue this practice, then it was obligated to seek a definitive U.S. Supreme Court review of the constitutionality of the procedure. (SSA dropped the practice.)

This legislation established the current policy context under which the disability program continues to operate.

The Amendments of 1983: The Modern Form of the Program

As mentioned, the Social Security program was running annual deficits beginning in 1975, and the assets of the trust funds were being drawn down to make up the shortfalls. Moreover, the stress on the program's financing worsened considerably, even after the financing changes of 1977 that improved the long-term position of Social Security. But the short term continued to be problematic. Indeed, the amendments of 1983 were signed into law in April, at which time the trust funds were projected to be entirely depleted in August. Thus, trust fund exhaustion and the attendant benefit "default" were only 4 months away.45

Initially, the 1977 effort seemed successful. The 1978 and 1979 Annual Reports of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Funds indicated a dramatically improved situation. But the poor economy continued to undermine the program's solvency. In 1980, price inflation hit 13.5 percent, while wage growth declined by 4.9 percent—producing a double blow to the program's financing by simultaneously increasing costs as revenues declined. By the time the 1980 Trustees Report was released, the trustees were calling for stop-gap financing changes.46 In the 1981 Trustees Report, more dramatic action was urged.

In May 1981, the Reagan administration proposed a package of policies designed to address the financing problems. Some aspects of this package were seen as quite drastic, especially an immediate 38 percent cut in early retirement benefits. Within days, the Senate passed a "sense of the Senate" resolution by 96 to 0, essentially rejecting the administration's proposals.

Following this failed effort, President Reagan appointed a bipartisan commission—the National Commission on Social Security Reform, also known as the "Greenspan Commission"—to study the program's financing and make recommendations to the Congress for legislation to address the financing problems. After some considerable difficulty (Light 1985 and 1994), the commission produced a consensus final report that made 16 proposals for both long-term and short-term policy changes. Four of the commission's recommendations increased costs slightly (mainly to make benefits more generous for women), and 12 proposals lowered costs fairly significantly. However, the commission was unable to agree on the final increment of desired savings, leaving 0.58 percent of payroll of the long-term deficit unresolved.47

"This bill demonstrates for all time our nation's ironclad commitment to Social Security."

President Reagan on signing the bill

The Congress basically adopted the commission's recommendations without much modification and closed the remaining long-range gap by increasing the FRA from age 65 to 67. President Reagan signed the bill into law on April 20, 1983.

The following items are among the key provisions of the final law, as highlighted in Svahn and Ross (1983).

- Extended coverage to all new employees of the federal government and to employees of nonprofit organizations. States were prohibited from opting out of Social Security if they previously had opted in.

- Shifted the payment date of the annual COLA from July to January (meaning no COLA was paid in 1983).

- Raised the FRA from age 65 to 67, on a phased basis beginning in 2000.

- Introduced the Windfall Elimination Provision, drastically reducing Social Security benefits for individuals receiving a pension from employment not covered by Social Security (principally government employees).

- Advanced the implementation of the tax rate schedule from the 1977 law (but did not change the top rate).

- Increased the self-employment tax rate to twice that of the individual rate (previously it had been lower than the combined employee/employer rate).

- Included up to one-half of Social Security benefits as taxable income, with the proceeds to flow back into the Social Security trust funds.

- Made the operations of the Social Security trust funds "off-budget" starting in 1993.

The actuarial assessment of the 1983 legislation was that it closed both the short-term and the long-term financing gaps. The annual Trustees Reports for 1984 through 1987 showed the program to be in close long-range actuarial balance.48 Of the policy changes made in 1983, approximately 52 percent of the savings in the short run came from taxes, 34 percent from benefit changes, and 15 percent from the changes in coverage (Svahn and Ross 1983).49 In the long run, the proportion was approximately 41 percent from taxes, 38 percent from various changes in benefits (including the increase in the retirement age), and 21 percent from coverage changes (Svahn and Ross 1983).50 (The increase in the retirement age accounted for 34 percent of the total net savings produced by the 1983 legislation and was about 90 percent of the savings from benefit changes (Table 7).) The 1983 law produced the current policy form of the program. Major policy innovations were introduced in the law (taxation of benefits, increase in the retirement age, coverage of federal employees, etc.) that still characterize the program to the present day. Most importantly, the financing arrangements made in 1983 have driven the program's dynamics ever since (see the discussion in the section—The Debate over the Program's Future).

| Amendment changes | Short-range, 1983–1989 ($ in billions) |

Long-range, 1983–2057 (expressed as a % of payroll) |

|---|---|---|

| Tax changes | 85.5 | + 0.86 |

| Benefit changes | 55.7 | + 0.79 |

| Raise retirement age | 0 | + 0.71 |

| Coverage changes | 25.0 | + 0.44 |

| Total | 166.2 | + 2.09 |

| SOURCE: Social Security Bulletin, 46(7): July 1983, Table 1, p. 42 and Table 4, p. 44. | ||

| a. Figures are projections as of July 1983. | ||

Post-1983 Developments

The 1983 amendments were the last major Social Security legislation of the twentieth century. Indeed, no comprehensive changes have been made to the program in the years since. There have, however, been a few important "single-issue" pieces of legislation.

Legislation in the 1990s. The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 raised the percentage of Social Security benefits subject to federal taxation from 50 percent to 85 percent (subject to certain thresholds).

The Contract with America Advancement Act of 1996 prohibited the receipt of Social Security or SSI disability benefits if drug addiction or alcoholism was material to the person's disability.

The Ticket to Work and Work Incentives Improvement Act of 1999 created the Ticket to Work and Self-Sufficiency Program, which provides disability beneficiaries with a voucher they may use to obtain vocational rehabilitation services, employment services, and other support services, with the goal of returning disabled individuals to paid work.

Ending the retirement test. As previously noted, the original Social Security Act of 1935 had an absolute prohibition on work for retirement beneficiaries, as benefits were social insurance, replacing income lost as a result of retirement. Social Security benefits were not pensions, which are paid when the pensioner reaches a certain age.

This prohibition was first relaxed in the 1939 amendments when the concept was introduced of allowing a certain amount of earnings before benefits ceased. This became the first RET. The beneficiary population would much prefer to have their retirement benefits and their work income as well. So relaxing the RET was always popular with the public and was an easy way for Congress to liberalize the program without any attendant political push-back. In fact, from 1939 through 1982, the RET was liberalized in this way 21 times (SSA 2010).51

In 2000, this process reached its conclusion for beneficiaries at or beyond the FRA when the Senior Citizens Freedom to Work Act was enacted into law. Demonstrating the political popularity of this form of liberalization, the bill passed the two houses of Congress on a combined vote of 522 to 0.

Under the provisions of this law, there is no RET for individuals who have reached their FRA. Such persons may continue to work full time and receive a full Social Security retirement benefit. For those beneficiaries who have not yet reached their FRA, there continues to be a RET of the familiar form. However, because the exempt amounts in the RET are now raised automatically each year with wage growth, the test for these beneficiaries has already been relaxed nine times since the passage of the 2000 legislation.52

The passage of the Senior Citizens Freedom to Work Act of 2000 is the major exception to the generalization that the post-1972 period is one of retrenchment in Social Security policymaking.53 At the time, the estimated cost of the repeal of the RET was $23 billion in the short term, but was projected to be "negligible" in the long term.54 For an analysis of the actual effects, see Song and Manchester (2007).

The Debate over the Program's Future

The amendments of 1983 established the general policy structure of the current Social Security program and, in particular, its current financing structure. The direct and dramatic result of the financing structure in the 1983 law was a massive buildup in the size of the trust fund reserves.

Historically, the Social Security trust funds have never been either fully funded or on a strict pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) basis. Rather, the trust funds have always contained what former SSA Chief Actuary, Robert J. Myers, characterized as a "partial reserve." We can conceptualize these two extremes (a fully funded system and a PAYGO system) as the end poles of a continuum. Over the decades, major legislation has tended to move the placement of the reserve in one direction or the other. Both the 1977 and the 1983 amendments shifted program policy noticeably away from the PAYGO end and significantly toward the fully funded end of this continuum (Myers 1993, 385–392).

The design of the 1983 financing scheme produced a large buildup of the reserve in the near term so that this source of investment income might help defray future costs when the "baby boom" generation began to move into beneficiary status.55 The effect of this approach to program funding can clearly be seen in Chart 3.

Trust fund reserves: Actual and projected, selected years 1983–2037

| Year | Trust fund reserves (dollars in billions) |

|---|---|

| 1983 | 25 |

| 1985 | 42 |

| 1990 | 225 |

| 1995 | 496 |

| 2000 | 1049 |

| 2005 | 1,858 |

| 2010 | 2650 |

| 2015 | 3,049 |

| 2020 | 3,146 |

| 2025 | 2,757 |

| 2030 | 1,833 |

| 2035 | 429 |

| 2037 | 0 |

Although the amendments of 1983 restored long-range solvency to the program, by the time the 1988 Trustees Report was released, the program showed signs of financing shortfalls, and when the next annual report became available, it was no longer in long-range close actuarial balance—a condition which persists to the present day.

In the 2009 Trustees Report, the projected 75-year actuarial deficit in the program was estimated at 2 percent of taxable payroll. In dollar terms, this means the program has a 75-year shortfall of approximately $5.3 trillion (in present value). Stated another way, after the trust funds are depleted (projected to be so in 2037), payroll tax revenues will be sufficient to pay only 76 cents of each dollar of promised benefits. This report was 1 of 21 consecutive, yearly reports in which the trustees reported that the program was not in long-range actuarial balance. These unfavorable annual reports are the principal framing constraint on policymaking and are the drivers of the idea that the program requires some form of policy intervention.56

The debate over Social Security's financing and policy "reform" began in a highly visible way with the work of the 1994–1996 Social Security Advisory Council. This final statutorily chartered advisory council issued its report in January 1997.57 The council was charged with a comprehensive review of the Social Security program and with addressing the long-range financing issue. However, the members of the council were unable to achieve consensus on any set of recommendations and instead split into three factions, each advancing a different approach to Social Security reform.

The maintain benefits faction advocated retaining the traditional program and restoring solvency through a combination of relatively modest changes in tax, benefits, and investment policies. The personal security accounts faction proposed cutting benefits and diverting 5 percentage points of the 6.2 percent payroll tax paid by employees away from the trust funds to establish individually owned private equity investment accounts, in lieu of full traditional Social Security benefits. The third faction, advocating individual accounts, proposed creating similar individual equity accounts by imposing a new 1.6 percent payroll tax on top of the existing 6.2 percent Federal Insurance Contributions Act tax.58 None of these sets of recommendations resulted in legislative action.

During the Clinton administration, the president raised the issue of Social Security reform, principally in rhetorical form. In his 1998 State of Union address, President Clinton called upon the political process to "save Social Security first." As the federal government was then on the verge of its first budget surplus in 30 years, the president's proposal was that any surplus in the budget be used first to pay down a portion of the outstanding government debt, thereby indirectly benefiting Social Security in the sense of positioning the government to better meet its future obligations to the program. In the spring of 1999, the president proposed the more specific idea that any interest savings from the reduced debt be directly credited to the Social Security trust funds. Other than these two ideas, the Clinton administration advanced no comprehensive Social Security reform proposal, although the president did succeed in putting the issue on the presidential agenda.

Shortly after taking office in 2001, President George W. Bush established a commission to study the future of the program and to propose ways in which the system might be changed through the introduction of individual personal accounts, similar to the proposal made by the personal security accounts faction of the 1994–1996 Social Security Advisory Council. The commission issued its final report in December 2001, although no legislative action occurred on the recommendations.59